Imagine that a group of people could be brought into the present from a past time. And that group of people included Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Rosa Luxemburg, Vladimir Lenin and Otto Bauer (there are others but we can put them in the time machine another day).

Marx and Engels could be rightly proud that the ideas they set out in the middle of the nineteenth century about Capital have been vindicated on an enormous global scale. But what they would make of a great deal of ‘Marxism’ and the posturing of tiny sects waving rolled up newspapers at the military-industrial might of the new ruling classes?

One can only imagine their reactions as they discover ‘academic’ Marxism and various schools of ‘What Marx Really Said’ and more alarmingly, ‘What Marx Really Meant’. Marx might be in such a fury that the pen is discarded for the sword and he reverts to the fencing practice of his youth. It would be more effective than wasting time with polemics and certainly more satisfying.

Rosa Luxemburg would immediately understand the development of capitalism in China, India, Nigeria, Brazil and around the world. She would take note, fire off an incendiary pamphlet on the state of the world and throw herself into building a serious political and revolutionary opposition. She would hit the left like a whirlwind in a warehouse full of feathers.

Lenin would simply roll his sleeves up with the grim realisation that in Russia everything would have to start once more from the beginning.

But Otto Bauer might walk along Karl-Röwe-Gasse to the Margaretengürtzel and consider that something practical had been created and has delivered real benefits to the working class of Vienna for well over one hundred years.

And what would Friedrich Engels think? He wrote three articles in 1872 which were eventually put together and published as a pamphlet called The Housing Question. Part of Engels thesis was that capitalism cannot solve the housing crisis. The weight of this idea is borne out by a cursory look around the world; more than one billion people live in slums and many million more are homeless or live in overcrowded and unsatisfactory housing.

He also, rightly, dismisses the ideas of ‘the petit-bourgeois’ socialists who believe that universal home-ownership is the answer. In Britain over 60 percent of households are owner-occupiers with around 30 percent owning their housing outright.This leaves around 40 percent of people who are renting with very little, if any, chance of ever being able to afford to buy.

Engels also pointed out that capital generally just shifts the problem around. A tour around Britain will show the gentrification of some areas – making them far too expensive for many local residents to live in – and the collapse of the housing environment in others. London avoids the worst visible depressed areas but any trip to parts of Sheffield, Sunderland, Newcastle, Leicester and many other cities and towns will reveal shocking levels of deprivation and housing estates with poor quality, expensive housing and depressed, demoralised and bombed out populations.

The arguement could be left there. But Engels was writing in 1872. Municipal government did not exist across much of Europe and the provision of minimal and ineffective public services were fragmented and dominated by Gradgrind, charitable and philanthropic thinking.

In Germany, Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, trade unions, strikes and demonstrations and political parties were either banned or heavily proscribed. There were no mass socialist parties or legal party literature. There was no welfare state providing health care, hospitals, clinics, free education, libraries and parks. The right to vote was limited and restricted to those with some sort of property qualification and generally excluded women.

By 1922, only fifty years later, much had changed. Revolutions had taken place in Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary and elsewhere. Universal suffrage was now prevalent across Europe. There were mass socialist parties, some with substantial political power (even if they often seemed afraid of that power). Huge concessions and reforms had been won by the pressure of trade unions and the workers’ movement; the eight hour day, elementary pensions, sick pay, holiday pay and more.

Which raises the question of how to write a pamphlet on the Housing Question in 1922? Or today?

It is an important question because it raises issues in relation to ‘reform or revolution’ and ‘reform and revolution’. People were conscious of this question in 1922, perhaps more so than today, because socialists, many who claimed to be Marxists, were in positions of nominal power within capitalist relations of production.

Robert Danneberg was a leading member of the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SDAPÖ). He opposed the First World War, defined himself as aligned to Austro-Marxism and was the author of the housing policy of the Viennese socialist administration. In a pamphlet Vienna Under Socialist Rule he suggested:

‘Capitalism cannot be abolished from the Town Hall. Yet it is within the power of great cities to perform useful instalments of socialist work in the midst of capitalist society. A socialist majority in a municipality can show what creative forces reside in Socialism. Its fruitful labours not only benefit the inhabitants of the city, but raise the prestige of Socialism elsewhere’.

This was published by the London Labour Party in 1928.

There is nothing like this in the Labour Party in Britain today. I’m not sure they even use the word socialism in any of their literature. The candle of idealism does not flicker even for a moment in the gloomy bunkers where the focus groups meet or the windowless rooms where policy meetings convene. I am convinced that if many Labour MPs were to visit the legacy of New Vienna they would see ‘development’ opportunities and grand possibilities to hand it all over to the private sector.

However, if one has an open mind and is inclined to start with an idea of socialism being about people rather than profit, and that there is much to learn from socialist history then walking the streets of the New Vienna of the 1920s continues to provide great inspiration. There is something fabulous about just being there, among the proud monuments to socialist ideals and the principles of equality and democracy in housing. It is by no means perfect but it is far better than a lot of the equivalents, both historically and contemporary.

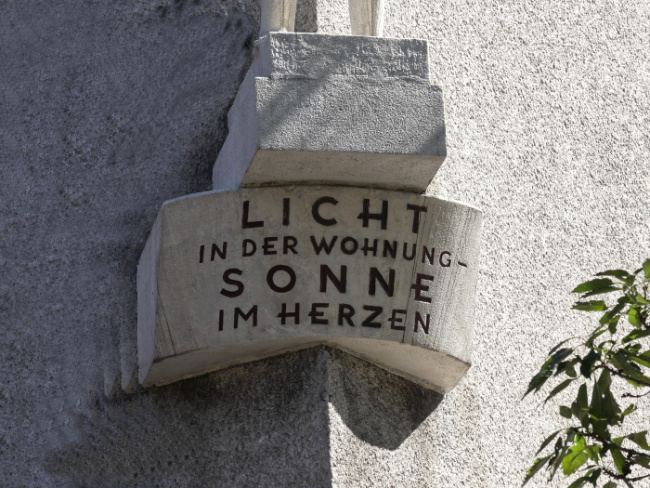

There were criticisms at the time of building, I’m sure there is disgruntlement today. The flats were seen as too small (although so were many private rented flats) and the literature of the time produced by the socialistss reveals a certain paternalism and corporatism. But interwined are powerful socialist slogans and imagery; ‘No Viennese Child Will be Born on Newspaper’ says one poster, advertising that every new mother will be given a layette for free.

The architecture has been criticised too although personally I like much of it. There is variation in blocks and they generally (at least from the outside) appear to manage that complex relationship between private and public space, the individual, and the community. The attention to detail is often lovely; nicely designed door fittings, lamps and signage, the use of wrought iron and brass, the presence of mature trees, flower beds and shrubs, variation in window sizes and shapes and designs.

The basic template that the blocks all share to some extent has enabled new blocks to be integrated into the idea of good quality, low cost, state subsidized housing, even though the designs are now different. I’m inclined to think that if the buildings all looked different then they would risk ‘standing out’ in a perhaps eccentric way. As it is, they generally blend in, particularly where they are in streets with mixed styles of other apartment blocks. They have aged well and this is related to the principles of their building.

My one caveat (and I will explore this elsewhere) is to ask what the housing might have looked like if Otto Wagner, who died in 1918, had greater input? Many of the architects who designed New Vienna were his pupils or influenced by him. But what might New Vienna have looked like in a more modernist, or perhaps more boldly, art nouveau style? And of course, if there had been more money and less depressing pressure from the right, yapping about cultural wars, manufacturing hatred and acting in their usual corrosive and corrupt way?

These are now questions developing in my head and potential answers are slowly accumulating with further reading and more exploration of the streets and buildings themselves.

Catherine Bauer in her book Modern Housing wrote that ‘Housing is more than houses’ and it feels as if to some extent that’s been achieved. The housing of New Vienna was built according to a certain type of socialist principles; good quality, low cost, state subsidized housing. There is a strong identity because there is an expression of shared characteristics and shared values.

To the social democrats of the time that was purposeful and deliberate. It is a certain ideological quality. It is something more than just the quality of the materials of the buildings and their shape and arrangement on the ground. It is a quality which is difficult to define but it is a quality I’ve not encountered on the over priced badly built new housing appearing now in England.

I’m going to plan a Radical Walk on this small part of New Vienna. I’m not sure of the starting point yet but it will definitely include Karl Röwe Gasse and the Margaretengürtzel and the housing of Fuchsenfeldhof, Reismanhof, Ruemannhof, Metzleinstalerhof, Herwegh hof, Julius Popp Hof, Matteotti Hof and others.

I’m hoping Friedrich Engels comes along. It would be good to have a chat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.