A Sunday Afternoon Walk.

On the Hernalser Hauptstrasse there is a Turkish baker’s that sells the most delicious bread rolls and Mohnkuchen. The inside of the bread is as fluffy as one imagines a cloud to be. The outer crust just the right amount of crisp. I slice through the bread rolls and spread thick creamy alpen butter on both halves. Then I add butter cheese and chopped up spring onions and tomatoes. It is eaten slowly, to be savoured, to be enjoyed. The Mohnkuchen I put in my bag to be eaten later. It’s Sunday lunchtime with the lazy feel of a day that might last for ever.

It is only by walking the streets, day after day, walking around the perimeter of estates, through estates, following unlikely pathways, riding on the trams and U-bahn, that the full extent of Red Vienna becomes apparent. I’m approaching this using two tactics. The first is to visit places that have drawn my attention through reading books and websites.

The other is the craft of unmapped walking. To follow what feels to be hidden forces in the streets that magnetically pull one along, tugging the unwary stroller to unknown side streets, gently guiding into courtyards and alleyways, down a flight of steps that magically appear, previously unnoticed. Half sensed dreams and ghosts that create diversions along neglected back streets, past building sites, boarded up factories; what might be described as waste land, or sacred land or places where children play. Vacant, empty, derelict,neglected, commons, meadows, enclosures; the very land itself is draped in the keywords of class interests.

The only intent, and it is vague, is to walk westwards along Geblergasse towards some tree covered hills in the distance. One side of the street is in the beam of the hot afternoon sun, the other in the shade of cool shadows. There is never a moment when the street is empty of people. The slowness of walking enables the detail of the street to be observed, a window opens to the time before the world wars, a house that was once a part of the Austro-Habsburg Empire, a door knocker that announced the arrival of a thousand visitors.

The city is working its spell today and spinning the finest silken web to capture me.

David Hof

The David Hof was built on previously open land and is named after Anton David. He started his working life as a soap maker. He became a member of the Reichsrat in 1907 and was a member of the city council of Vienna from 1913 to his death in 1924. The architects of the development were Walter Broßmann and Alfred Keller.

This is rusticism on a grand scale in pastel colours of terracotta and burnt lemon. The delicate angles of alternating windows provides a subtle riff along the main facades. A column of raised eye-brow arches encourages a ‘look at me’ sensation.

School – Julius Meinl Gasse

The school is from 1913 and is a useful study of the city in the times of Empire. The architecture, principles and politics of Red Vienna didn’t suddenly pop out of the history books in 1919. There was a long gestation, hidden currents among the intellectuals and mass of workers, ideas of the fin-de-siecle, the impact of the Secession movement, the swirling sounds and images of Art Nouveau and Modernism.

This may be the time of autocracy but the school is an example of something profoundly progressive; of the idea of high ceiling classrooms with big windows, the principles of light-flooded space, that liberates the children from their home environments, dominated by the dust and grime of factory production and never ending want. The building has a profound solidity, a rhythm of steady application.

Next door, an empty factory building which would have once been full of workers, perhaps some of them the parents of the school children who would peak through the railings at lunchtimes to catch a glimpse and say a cheeky word or two.

This type of walking is a freedom of, and on the streets, the simple pleasure of the accidentalism of what feels to be nothing much at all, and yet revealing years of history.

One of the pleasures of the casual unplanned walk is discovery. There are no expectations. One might walk for hours and miles and notice all sorts of things along the way, an unassuming building that on closer inspection reveals itself in a slow and enticing manner. A seemingly unplanned streetscape that has bought all the elements of mass and space together in an unexpected and delightful way. The sense of anticipation adds a frisson to the walk and then, at the end of the hill, past the Julius Meinl hotel, the Kongressbad, a municipal swimming pool.

Kongressbad

It announces itself, or rather the crowd inside, presumably watching some sporting event, declares its presence with the ebb and flow of the crowd cheering and gasping in unison. One imagines two teams immersed in the cool water of the pool involved in some intricate game of strength, skill, subterfuge and complexity.

The red and white layers are bold and bright and there are touches of modernism that give the whole ensemble an energetic zing. Part of the Red Vienna project was to improve the health of the masses, something that must have seemed more daunting in 1919 than it does today. The general health of the city population was poor, masses of people lived in slums, diseases such as tuberculosis were everywhere and at the time, incurable. One of the interventions by the welfare reformers was to use nature itself as a resource, to harness water, to make use of light and space and air.

The Kongressbad and adjoining park, was built in 1928 to plans by Erich Leischner. In an aerial photograph, the edge of the Josef Wiedenhofer Hof can be seen in the top right hand corner. That’s worth nothing because it shows how close it was to a large community of working class people.

Josef Wiedenhofer Hof

I had read about Rabenhof and Karl Marx Hof and Goethehof in advance and so had some preconceptions before I visited them (although nothing prepared me for their actual physical presence).

Discovery is different because there is no expectation, no preconceptions and sometimes this can be a fascinating approach. In this case, the Josef Wiedenhofer Hof felt as if it was encountered in its primary state with no adherent messages or written texts to form conclusions in advance.

It was a treat to discover this estate first as a group of buildings, designed and planned in a particular way, and only later to trace its history. My notes recorded, ‘impressive without being oppressive, powerful and dignified, courtyard full of trees and flowers, trees providing shade and fascinating shadow patterns on the walls, clean and well maintained, bright and bold modernism without lecturing anyone about architecture, despite the mass of the buildings a great feeling of space and light and air, it feels as if its a template for some of the best municipal housing of the twentieth century’.

I was delighted to later read about the estate and that it was designed and planned by Josef Frank.

Balderichgasse 25-27 / Zeillergasse 10-12

To put Frank’s achievement into context, it’s worth going to visit the block at Balderichgasse 25-27 / Zeillergasse 10-12. This is an enclosed block with a central courtyard. It was built between 1922 – 1924 based on plans by Karl Ehn. There are 164 flats.

This is a solid construction but I found it rather gloomy, even on a bright sunny day. It must be remembered that the city council bought land where it could, particularly if the land was cheap. Some of the buildings of the 1920s had to be placed on sites that were part of an earlier street plan, and within the context of previous pre-war planning decisions. Architects like Frank wanted buildings to be orientated to maximise the amount of sun each apartment was bathed in during the day. This was not always possible.

It’s also worth remembering that the overall housing project was a development of ideas and practice. The construction of each new block must have raised new ideas, based on the gained experience.

This block, and Josef Wiedenhofer Hof act as a good counterpoint to each other.

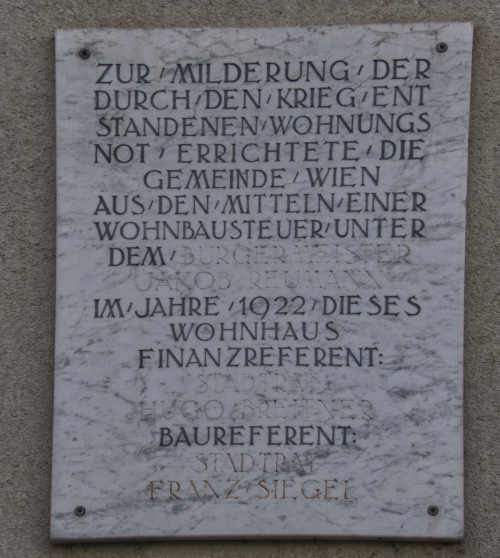

The block has a tablet with the inscription:

“In order to alleviate the housing shortage caused by the war, the municipality of Vienna uses the funds from a housing tax to build the following under the mayor Jacob Reumann, Finance Director, Hugo Breitner, Building Officer and City Councillor, Franz Siegel”.

I wonder if this was plaque was allowed to remain here during the fascist period? The answer to that small question would reveal a great deal.

Türkenritthof

Türkenritthof was built in 1927 on land that had been acquired in 1917. It seems difficult to imagine that anyone in the city council was considering urban planning during the First World War. But people were hungry in Vienna, the settler movement was beginning and the news of revolution in Russia would be sharpening the political instincts of both the ruling and working classes.

Perhaps it was the revolution that spurred the city planners to consider that the Austro-Hungarian Empire might be next to crash and burn and that it might be prudent to consider how to placate and satisfy the demands of well-trained and well-armed troops, with battle experience, marching through the streets, being joined by factory workers, transport workers and that great mass of unorganised workers in offices, services and shops. This is speculative imagination but not impossible. It had already happened on the streets of Moscow, Petrograd and hundreds of other Russian towns and cities.

There is something peculiar about the naming of Türkenritthof and the weird statue that dominates the main entrance. That it is difficult to decipher is but a matter of aesthetics. That it represents the defeat of the Ottoman Turks by the Holy Roman Empire is a political fact that seems to oddly grate against the ideas and principles of the socialist minded city.

From the date of this battle until the end of the 18th century, there had been annual celebration parades in the Hernals district. Even the Emperor became weary of the ribaldry and goings on and they were banned. There hadn’t been one from 150 years when it was decided that they should be celebrated with a statue. There is a strange odour of culture wars about this but it is unclear who the protagonists might have been.

The estate itself was built in 1927 and it’s well designed. The central portal (apart from that bizarre statue) provides a strong pattern to the entrance and egress and creates a powerful barrier between the residential housing and a busy main road. If this was more open it would feel like living in the central reservation of a dual carriageway.

During the civil war of February 1934, it was a scene of fighting and there is a memorial plaque to Leo Holy who was killed there. In the time of the fascist reaction part of the building was used as a police station and detention centre.

There was more that afternoon, a visit to the cemetery, an exploration of some post-war building (two girls were constantly circling the estate on a scooter, taking it in turns to either be the person who steered or clung on behind), and then walking north into the bourgeois suburb of Gersthof.

A different environment, of large villas and solid bourgeois housing of the nineteenth century. There were fascists, right wingers and reactionaries among the working class; some members of the Heimwehr started their political trajectory as strike breakers and scabs.

However, it was in suburbs like this where the wealthier fascists lived and they had the money-power to pay for newspapers and full time organisers and meeting halls and the fines of the street hooligans. One can imagine the types of people; surrounded in luxury, furious that they were having to pay higher taxes to pay for public housing, emasculated by the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, psychologically caught in the trap of capitalist ideology, failed expectations, some with a sense of an unfulfilled and empty life. Into this emptiness flowed the gushing sewage of hate, anti-semitism, the promise of power to the little man, the hope of a community, even if it was a community of coarseness and hypocrisy.

I caught a tram, grateful to sit down for a few minutes on the way home. Everything of immense interest as the tram swayed along, the displays in the shop windows, the fashions of the people in the street, those outside cafes with drinks and snacks, the buildings. I noticed a building forming an impressive stop-point to a small side street. Another Gemeindebau. I made a note. That’s where I’ll go tomorrow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.