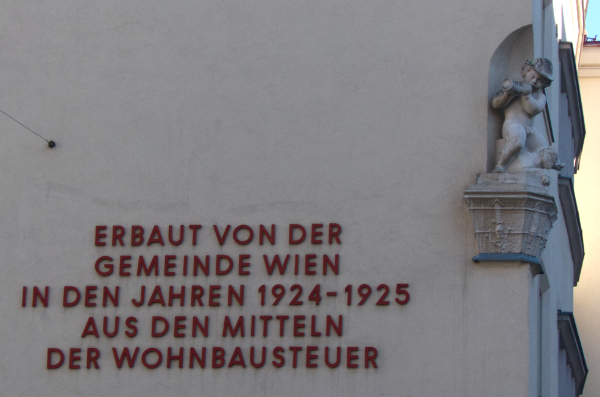

It is not obvious that there are over 1,500 apartments in the Sandleiten estate, housing perhaps 5 – 6,000 people. There is a powerful sense of air, light, space, nature. The original planning and architectural principles of Rote Wien are well expressed. The estate was built in phases between 1924 – 29 and is the largest which was constructed.

I am dropping a little into the local life. No longer just a tourist, no longer just observing surface appearances. Perhaps it’s the active community development work on the estates, perhaps it’s a friendly estate. I talk to half a dozen different people and first impressions are now decorated with real-lived experiences explained in conversations.

The first is an elderly woman who is slowly walking a dog. I can’t remember how we started talking but once we start, it’s a mix of German and English. She tells me she lives in a studio which, with bills, she pays around €650 a month. I explain that in London that would be considered very cheap. She pulls an astonished face and shakes her head incredulously when I explain that one room, with shared bathroom and toilet can be €1,000 a month.

Do people in Europe realise how expensive and poor quality so much of the housing in England is? Do people in England realise how high pensions are in parts of Europe, or the quality of the rented housing, health and social services? It’s no surprise the landlord class supported Brexit. Anything that helps to keep people in a little nationalist box that can be easily controlled serves their interests.

‘It’s too expensive’, she says

‘Housing is too expensive all around the world for people’

She nods in agreement, and chuckles in a sort of global proletarian style.

I ask her if she likes living here. She shrugs and pulls a face and explains she would rather live in the block opposite, which I think (we struggle with language here) is a cooperative or community housing. The only word I think I understand is something I translate as ‘comrade’. This can’t be right. Although perhaps it is. Perhaps it should be.

‘What’s the problems?’ I ask.

She tells me it’s the people.

‘They sit on the benches and throw their rubbish on the ground’.

She mimes people eating and smoking and drinking and throwing all the debris to the floor.

‘They throw mattresses in the streets’.

She mimes a mattress being thrown from a balcony

I look carefully at our surroundings and cannot see so much as a cigarette end. Throughout the estate I see no litter. I would describe it as spotlessly clean.

Obviously great care is needed in analysing this sort of vox-pop. But care needs to be taken with larger and more thorough surveys too.

Years ago I worked for an organisation called The Safe Neighbourhood Unit which was set up by the Home Office after the Brixton Riots in 1981. Our brief was to find out ‘what people were actually thinking’. We worked on what were described as the ‘worst twenty estates’ in London. Only one was really horrible.

The other nineteen certainly had problems but often not what people thought they were. One estate in West London had two distinctive parts. People in the southern part had nothing but bad things to say about the northern part, and vice versa. Some young people were frightened to go out and some elderly people liked the estate and said everyone was friendly and helpful. I suspect that any survey carried out on the Sandleiten gemeindebau would generate similar responses.

We swop English and German words. She is a good teacher.

‘You have taught me some English’, she says

‘And you have taught me some German’, I reply, and add, ‘Es war alles kostenlos’

We both laugh at this and go in different directions.

On the pavement there’s a notice advertising a knitting club. I go through the entrance to look at the building. A group of women are sitting around a table. There isn’t any knitting going on but they are haveing a conversation where everyone speaks in a loud growling Viennese dialect which might date from the Austrian revolution.

A community worker comes over to talk to me and shows me the space that used to be a wash room and then takes me upstairs to see the space that was once the cinema. Imagine that. A council estate with its own cinema. It is about to be brought back into use by the Academy of Fine Arts.

I ask her what the estate is like. ‘Elderly people, migrants, young professionals’. This sounds like a good mix to me. She says that people are worried about the possibility of the right doing well in the elections on Sunday. I get the sense, not just here, but in other conversations, that when the subject of immigration comes up, people are wary. I would be too. You don’t want to discover that you’ve just met a right wing pub bore emboldened by the domination of social media by right wing interests.

I point out that none of the politicians in England will say that key industries such as construction, agriculture, food processing, manufacturing would not function without migrant labour. Nor would the health service, retail, the privatised care sector nor the hospitality sector. She pauses and looks at me; I’m not a right wing schmuk. She says it’s exactly the same in Austria.

Before I leave she gives me a present of a book about the work they’ve been with the community. I flick through the pages looking at the photographs. Art projects, social events on the estate; and pictures from the 1920s.

On the way out I notice a poster on the door advertising an oral history project. There will be people living here with handed down memories of the fighting during the civil war when the police and army fired artillery at the estate from the nearby Kongresspark. Memories passed along perhaps even of the revolution in 1918. The days of Rote Wien, the growth and take-over by the fascists, the Second World War, the Russian occupation. Even fragments of these stories will reveal a great deal.

My mum lived through the Russian occupation of Silesia and describes sleeping under piles of sawdust for weeks. Of living on potatoes until one day she and her friends discovered a milk churn full of treacle in a bombed building. ‘Then we had treacle with our potatoes’, she said.

We were talking one afternoon and I mentioned something about a forester, I can’t remember the context. ‘I had a school friend who’s father was a forester’, she began, ‘She lived a few houses away from where we lived. When the Russians came, her father shot her, and her mother and then shot himself’. She said it matter of factly and didn’t add anything. These stories too, here in Vienna, here in the Sandleiten gemeindebau.

I talk to a young man with a beard who has just ridden his bike fast from somewhere. He is dripping with sweat and takes his crash helmet off. He explains some of the layout of the estate. He seems to be in a hurry so I try not to hold him up.

‘What’s it like to live here?’ I ask him.

‘It’s great, really great’.

I get the sense he’s thinking, ‘I cycled really fast to get home on time and now I’m being held up by a questionnaire’. He was good natured though.

Rosa Luxemburg Platz is a superb example of public space. Real public space as opposed to the privatised pseudo-public space that modern developments so often generate. A statue of a small child holding a large pile of books. A most impressive Gothic-modernist library building.

It must have been even better before the dominance of motorism added the industrial metal mass of cars, a spoiling of so much urban landscape. Cars change the look and feel of streets. They have no aesthetic qualities so add nothing of beauty or craft. They take a disproportionate amount of space and as cars continue to become super-sized this problem grows. The speed and mass of cars prevents street play and street encounters, and therefore street life. And street life cannot be planned or bought in a shop or created through focus groups. But when it works well there is nothing quite like it.

I notice on a bookshop window some pro-Palestine slogans. I’m about to take a photograph when I realise that the woman inside is looking at me. I find the door so I can go in and explain myself. Once inside she stands up to greet me. She is wearing a pink headscarf and long dress with a black and white swirling pattern.

She tells me how people are worried about the election on Sunday, the growth of the far right and ongoing racism in the city. She has visited London several times and says she thinks it is friendly and freer. She explains that she was born in Vienna and it feels as if conversations keep happening about things that by now should be sorted out. We discuss the history of anti-semitism in the city. ‘Now’, she says, ‘the right wing say that anti-semitism is being imported’.

Suddenly Rote Wien is alive; it is no longer just a research project. The arguments and class lines from the 1920s are still ongoing. And I wonder if the conscious symbolic value and power of the estates continues to aggravate the right?

England once had a fine tradition of well built council estates with gardens, services, direct labour maintenance and much else. From 1980 onwards this infrastructure, and the values it represented, has come under relentless attack by the Tories and the wet Tories that now dominate the Labour Party.

In Rote Wien the architects, designers and layers of the social democratic leadership and city hall bureaucrats shared some common sense of principles and values. That the housing should be good quality and inexpensive. Gardens and open space should be used to utilise nature’s powers of air and space and light to support the physical strength and psychological harmony of the people. And values such as these once influenced the Labour Party’s approach to housing in Britain.

Now this has changed. Everything is underpinned by capital. And that smears a greasy film of money and profit on housing, health care, education, transport and all everyday objects. It means that the only essential value of our environments is the rule of cash.

But the developers, speculators, volume house builders and politicians cannot admit this. Hence a huge industry of marketing and advertising devoted to telling us each day how fantastic capitalism is. It needs this head fixing industry because the objects of everyday life struggle to emit genuinely social signals. It must be done for them.

When housing is built for through taxes, without any expectation of profit, then other values can shine through with greater light. The city council of the 1920s, despite the criticisms that can be levelled at it, had a genuine belief that producing a good social environment would be good for the people. And here I think the housing achieves the values of honesty and social commitment that continue to resonate. Something that little public housing in England has achieved for fifty years.

The design of all the blocks, large and small, has a cosy Biedermeier-ish comfort and perhaps reflects those early nineteenth century values of community and domesticity that people still crave. Ornamentation and design are used to provide a nicely balanced decorum with a slightly cheeky edge. The overall effect is that of a satisfying comedy drama theatre with a happy ending.

None of this is accidental. The guidelines for the original competition for this housing stipulated that there should be large inner courtyards and plenty of play space. The architects and planners were influenced by both Otto Wagner and Camillo Sitte and this is well expressed in what was built and how. The central square, Matteottiplatz was consciously modelled on a square of the type that could be found in a Renaissance town. The overall amount of overall space was increased by the laying out of Kongresspark a few minutes walk away.

Of the overall site, 22 percent has been built on and 78 percent is ‘space’. The building of the original estate included doctors’ surgeries, pharmacies, a post office, shops, workshops, a pub, offices for the police and fire brigade, laundries, bathing facilities (slipper baths), welfare rooms, a hall, a kindergarten, a library, theatre and cinema.

There is a great deal of community activity across the estate. The formal meetings, bookshop, knitting club, library, drop in centres, a pottery workshop and much more. I notice too the number of people who are sitting in the gardens reading, groups of friends talking, people listening to music or stories through headphones. I spend a couple of hours walking around and sitting at various places and when I leave, there are still people in Matteottiplatz talking who were there when I arrived.

Perhaps they are discussing the forthcoming election. Perhaps they are sharing memories of the estate. There are many memories of Rote Wien. But who is learning from the lessons?

note: all the photographs are of the Sandleiten estate and were taken by the author. Please contact me if you would like to reproduce any of them

You must be logged in to post a comment.