The U-bahn train on line U3 came to a momentary stop outside Florisdorf station. It was a moment to catch up with myself. It’s like you suddenly become yourself again, remember who you are, waking up from a walking daydream through the city streets.

An elderly woman walked past me pulling a shopping trolley. She pointed at my camera and then the building I was about to photograph and said some words I didn’t quite catch as she walked on. She turned her head, we were so close in time and space, her eyes flashed images of a child in a war, arial bombardment, Russian troops, screaming, people running through burning streets, the occupation. And then her eyes sparkled again and she smiled and raised her hand as a gesture of goodbye as she walked on by.

I sit inside a local bakers in Florisdorf and eat lunch. The woman who is serving comes and clears the ledge that I’m leaning on. It’s one of those ledges that enables a view out of the window. She cleans it quickly and effectively. I move my roll so she can clean underneath it. She thanks me. Then I move my cake so she can clean where it’s been. She’s a worker that’s for sure. She sells her labour time by the hour. She is never her real self when she does so. I wonder what she dreams about and I would love to spend the afternoon in the pub with her.

A large man asks if he can sit down. I pull my chair along to give him more space. We both sit and eat and then it’s time for him to leave and we exchange comments about how good the food is. He wishes me well and leaves to spend the rest of the day selling his labour power to the employer. And when he does so, he cannot be who he really wants to be.

The square in front of the bakers is full of people. It’s what the management world call ‘diverse’ but that same management cosy club, for all its talk, never lives in this.

The whole world is represented here; with the skills to build 60 storey buildings, raise children, deliver health care, code software, drive lorries half way around the world, make machines work, move every raw material and turn it all into commodity-image-objects. If only it could be organised.

Two elderly men sit on a wall discussing the world. ‘There’s going to be war’, ‘you can feel it’, ‘another one dressed up as a Christmas tree’, ‘they know nothing’, ‘what about how we live’. It is clear that they are working class. All this energy of how to change to world; how to bring it all together.

Why is this elderly woman wearing such a thin coat? Why is this person wearing plastic shoes? Plastic shoes don’t keep the feet dry and warm. Why are so many people counting so carefully the money they spend? Why are these young men sitting around so frustrated that they cannot find work where they could develop their dignity in being creative?

I wait for the street light to change from red to green. A man in orange jacket and orange trousers with reflective bands moves a heavy sign where the road work crew are working. I step back to avoid being in his way. He thanks me. He’s working class. Just look at his hands and face.

And so I walk through Florisdorf to visit the Karl Seitz Hof. Along a busy road. And then, there it is. Like seeing the sea over the curve of a hill.

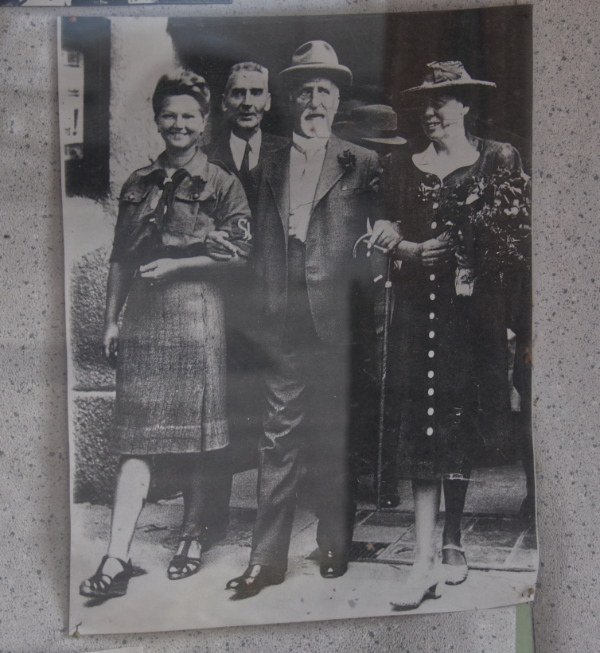

One of the first things to notice is the collection of photographs of Karl Seitz in a frame on the side of a building. As a student, with his wife Emma, as a member of Parliament, as the Mayor of Vienna. In a frame with a Gestapo storm trooper thug threatening him. Seitz was imprisoned in Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944. The photograph. below shows him on his release in Vienna in June 1945.

I notice the people just sitting around chatting. The free and easy atmosphere. The understated power of the first blocks that you see.

A track suit type with a drug-face and a large, powerful dog glances over at me. He goes out of the estate. And then he comes back. While he is coming back, I’m watching an elderly women with a shopping trolley walking across the courtyard.

‘Hey Vito!’ the man says (this is the dog’s name). The dog leaps up to say hello to the woman and is admonished by the man in the track suit. ‘Calm down!’. She takes the dog’s large head in both hands and gives it a good shake. The dog is beside itself with glee. There’s no edge. I encounter him later in the street with two of his friends. The dog is reined in so it won’t be in my way and they move into single file so I can pass them on the pavement without having to walk into the road. This sort of street life needs to be closely observed because it speaks loudly of certain things.

I wish I knew someone on the estate who could really show me round.I can’t even begin to lightly touch the surface. I have no idea what it’s really like, the intrigate web of community and people.

Instead I just sit. It’s an underrated skill. I sit for quite a long time. Eating a cake, playing with my camera, making notes in a pocket size notebook. Watching the way the light changes. And as ever with observational sitting, the relationship between foreground and background starts to change; and you notice things. The tiling of the doorways, the curve of the building, the use of circles as a decorative motif.

At first it appears that this vast space between the buildings is empty. And then an elderly man walks across. And then another. A middle aged woman with a bag of shopping. She calls to someone I can’t see. A young couple deep in conversation. A street tough who muscles his shoulders as he walks past.

Another elderly man. Another shopping trolley. A kid on a scooter. A woman with a pram and a young child sits on the bench nearby. A group of people are beginning to form at what I think must be a school or kindergarten building.

It’s just observation, and it’s a dubious methodology, but I’d say that there are people from a wide range of backgrounds and nationalities and ethnicities. That’s the impression.

Some people look at me discreetly, you can sense these things. Not in a suspicious way but more in a ‘do I know you? have you had a hair cut? I haven’t got my glasses on, is that so-and-so?’

I still have no idea what it might be like to live here but at least the environment is trying its very best to help the people as much as it can. The natural resources of air, light and space are being used in a way that is of mutual aid rather than of ‘domination’.

I am beginning to discover all sorts of very mixed and contradictory emotions charging around inside me. I am in awe and love of this. Awe that it is so brilliant. Love; it’s like meeting a stranger and discovering that you have a mutual and magnetic attraction; the atmosphere changes.

And fury. I am furious that nothing like this has been achieved in England for almost fifty years. When I look up and see a rainbow flag next to a flag of the anti-fascist Shutzbund of the 1920s I feel that every minute not working to kick over the pricks is a minute wasted. I must have got some grit in my eyes. It must be the dust and the wind.

The whole estate has such a lived in feeling. It’s like a favourite armchair where books have been read, day dreams and life lived out. It is so uplifting that it stays with me for a long time afterwards. Maybe I should toughen up; become fatuous in that hard right-wing Labour Party sort of way. Indifferent to the plight of pensioners but so concerned with the profits of the volume householders. Instead I feel that if I have to hear ‘twenty percent of the housing is affordable’ one more time I might just puke. It of course suggests that 80 percent isn’t affordable (so who does live there?).

I note the washing hanging over the balconies. A sheet is being flapped around in the wind, as if it’s a ghost. I’m looking up at this when the sheet is suddenly defeated and a woman is folding it in triumph. This is unexpected for both of us and she catches my eye and smiles.

Compare this with all those blocks of flats in London now controlled by ‘management companies’. Sometimes based off-shore, complicated structures so no-one actually knows who is responsible. Sanctions against washing on lines, but nothing ever seems to get done about letting and sub-letting and sub-sub-letting.

CCTV and private security. Without any idea that the best security on an estate is the community. Thinking about it, I don’t remember seeing CCTV on any of the Red Vienna estates I’ve visited. I’ve seen people leaning on their balconies and looking out of their windows. I’ve seen people in the courtyards and gardens with their friends, drinking, smoking, talking. I’ve seen groups of teenagers – often with fine tuned antenna for things that may be suspicious.

I’ve been stopped in a casual, serious sort of way. In the way that people who care about their environment do. Sussing me out. When they’re satisfied I’m not a wrong ‘un they talk to me. But there’s been something there underneath, and I’m aware it might not be so friendly if there was anything amiss. But no, I’ve not seen any security guards or CCTV.

The Seduction of Curves: The Lines of Beauty that Connect Mathematics, Art, and the Nude by Allan McRobie. A wonderful book that describes the underlying mathematics of why we like curves. Particularly each others curves. That’s the key bit.

Not one developer, not one property speculator, not one housing profiteer or luxury landlord has a clue what it’s really like to be working class. How hard a fight it is. And here, a record seller on a working class estate.

On each of the large estates I’ve visited, they all have a number of what I now call ‘community trollies’. I have seen these being used to take washing to the communal laundery, moving car wheels, as go-carts by gangs of children, moving furniture and….even for putting the shopping in. Jane Jacobs would have approved. But I don’t think I’ve ever seen them referenced in a developer’s presentation about ‘building community’.

The estate was built between 1926 to 1931 as a garden city, designed to be a ‘city within a city’. The architect and planner was Hubert Gessner. It was originally called the ‘Garden City of Jedlesee’ (one of the areas in Florisdorf). There were originally 1,173 apartments and as can be seen from the photographs, large amounts of green and open space. When first built there were shops, communal laundries and drying rooms, a restaurant and a coffee house.

It was renamed Karl Seitz Hof after the Second World War to commemorate the role of Seitz as the mayor of Vienna when the housing of Red Vienna was built.

Seitz had been a leading member of the Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, (SDAPÖ) and involved in the anti-war protests of January 1918 which spread across the Austro-Hungarian Empire. These happened just weeks after the Russian Revolution of October 1917. In early 1918 there were strikes and demonstrations across Germany too. In London, Sylvia Pankhurst wrote in her notebook of street based anti-war meetings being attended by soldiers in uniform. The war might have been ended nearly a year before it did. Think of all the lives saved.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire both collapsed from within and was pushed to extinction by workers’ and soldiers’ councils from below. Seitz became the first President of the new republic. As an active socialist before the war he had been a strong advocate of educational reformer, of creating a secular and progressive school and college system. When the Clerical Fascists came to power after the Austrian Civil War in Febrary 1934 he was arrested and removed from all his formal positions. The socialists, trade unions and opposition movements were banned.

Florisdorf had been a large industrial area with a huge locomotive works. A centre of working class production and of socialism and trade unionism and a particular type of reformism. It would do well to study this reformism and its political trajectory because it has more in common with how Western Europe is at the present than the Bolshevik experience in Russia. And it is also from this reformism that this particular housing and welfare programme developed.

There is nothing being built like it in Britain now. Nothing remotely as reformist, as progressive, as clever and thoughtful in all aspects; building quality, aesthetics, committment to low cost rents and tenants rights, the provision of a full range of medical, welfare, educational and social facilities.

And the moral of this tale? If we want decent housing then we must fight for it.

We – the workers, the building workers, factory workers, machine operators, network engineers, service workers, nurses and health care workers, transport workers, the woman in the bakers, the man working on the road, the tenants, the dispossed, the artists, musicians and writers, the freaks and oddballs – must take control.

You must be logged in to post a comment.