There are many routes to follow in tracing Red Vienna. Walking towards a planned destination; walking as a means of discovery, walking as an ambient experience within the envelopment of the city. Walking as both a journey and a destination.

There is no need for rules or dogma. Chance, accident-ism, everything and anything. Walking in a line along a wide straight road. Walking in a non-linear fashion, catching the streets on the basis of almost imperceptible shapes that are only fleetingly seen. Is this a lucid dream? I read the term ‘politically charged urban architecture’ in Eve Blau’s book The Architecture of Red Vienna 1919 – 1934.

I decided to walk along the Hernalers Hauptstrasse, just to see where it might go, towards the wooded hills that I often saw in the distance, in the morning when I went to buy rolls and cakes. Along the way I came across the Eifler Hof, designed by the architect, designer and artist Otto Prutscher and built between 1930 – 1931.

These are only preliminary notes. I need to read at least two or three good books on Prutscher before anything of substance could be said. But it struck me that these first and early impressions might be worth recording. And it made me realise that there is interest in studying Red Vienna through the work of individual artists, architects and designers.

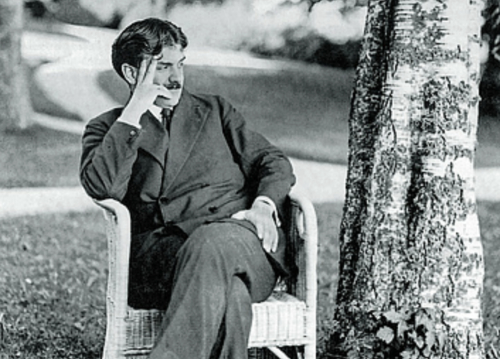

Prutscher became a student at the Vienna School of Applied Arts in 1897, the year of the formation of the Seccession Movement. His tutors included Franz von Matsch and Josef Hoffman. His training inculcated the importance of quality and craft.

Perhaps it’s too easily forgotten how difficult it is to create an artistic and cultural movement which may change the world. Vienna at the end of the 19th century was dominated by a monarchy that believed its long held power derived from the thousand year rule of the Holy Roman Empire.

The city was dominated politically by the Christian Socials who combined large-scale improving infrastructure works with socially conservative ideas and anti-semitism. That particular version of the world was ended by the First World War and revolutions in Russia, Germany, Hungary and Austria. Barricades, street fighting, mass strikes, factory occupations, food riots, demonstrations and workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

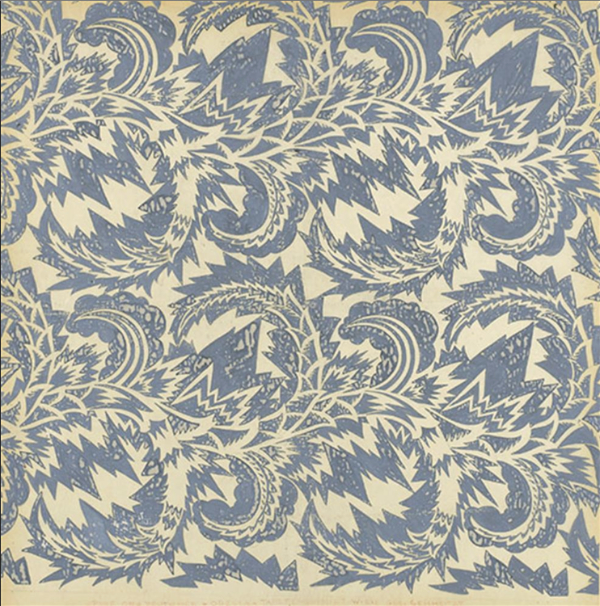

It is within that context that Otto Prutscher trained as a carpenter and became an artist, designer of furniture, glassware and wallpaper, an interior designer, an exhibition designer and an architect. In the 1920s he designed four Gemeindebau for the socialist council of Vienna.

Eifler Hof

The front of the building is on the Hernalers Hauptstrasse, a busy main road which has the unusual characteristic of seeming to fade away. I walked along it one day and ended up in the Vienna woods.

The trams come and go and it’s easy to get into town. There’s something well-organised and satisfying about the trams. They have a muscular presence and as they have dedicated lines, and weigh a great deal, even the most obnoxious SUVs get out of their way. It’s good to know that sometimes public transport can triumph over motorism in such a way.

Having a tram stop right outside the front door makes one feel connected to the city and city life. And yet, once through the big iron gates and cast concrete entrance, a quite and tranquil open space is found.

I was waiting for someone to move before I took a photograph and an elderly woman with wispy air and bright red lipstick came slowly through the gate with her shopping trolley. She didn’t stop looking at me. Then I said ‘tag’ and she smiled and her face lit up and something very alive shone through her sparkling blue eyes. And she said, ‘tag’, in return but somehow we communicated a great deal more than just two words.

Heine Hof

The Heine Hof was built between 1925 – 26. It is named after the German poet and writer Heinrich Heine who was a good friend of Jenny and Karl Marx.

This is a narrow site and yet the layout, with the two courtyards, enables a meandering perambulation.

The use of arches and their positions breaks up what would otherwise be a long straight walk from one end to the other. It makes one feel as if it’s a little adventure to move around, rather than just stepping out, one foot in front of the other with no variation.

Centering a key part of the block to align with Leitgebgasse is nicely done. It creates a grandeur; not just of the Heine Hof itself, but in terms of adding to the overall street scape of the surrounding area.

Anyone who glances there must surely be impressed. The pink flush of the building gives a good sense of committment to the quality of the housing. The building is not shy about this, there is no quitely mumbled doubt of, ‘is council housing allowed to act in such a way?’. It’s a statement such as working class kids make with their sharp and smart street wear that always defies the money-power of their richer peers. A sense of cool is not something that can be commodified and simply purchased.

An elderly woman was sitting on a bench at one of the entrances. She refused to accept that I couldn’t understand what she was saying and acted out an event in which she showed me her shopping bag and said something about her heart (she patted her hand quickly against her chest).

From this charade, and the few words I understood, it was impossible to tell whether she had successfully fought off an armed gang or eaten something disagreeable. When the subject moved to Gemeidebau and Wohnung it was more of a conversation. She told me she lived in one of the blocks and, as she proudly pointed out, was responsible for some attractive gardening.

Lorens Hof

The block was built between 1927- 28. The Bebel Hof is next door.

The main facade of Lorenshof is afflicated by the most pernicious urban blight; motorism. The cars never stop and they drive too fast and make too much noise and cause far too much pollution. I accept that motorism won’t end overnight but a lot more could be done to trim its excesses.

There are substantial amounts of housing along main roads; people’s homes, where they live. Tenants rights and quality of living should have priority over other people’s noise and speed. Motorism degrades housing and the proud front facade of Lorenshof is slightly lost to the possessive individualism of stare-ahead drivers.

The arches of Lorenshof are similar to those of Heine Hof; a little bit arts and craft, a medieval cloister come to town. Once through the arches, the courtyard space is much quieter; there is a sense of calm and urban peace.

The statue, a mother and child, was created by the sculptor Rudolf Schmidt.

Hermann-Fischer Hof

The housing was built between 1928 – 29 along the Ybbsstrasse. It’s in a quite tree lined street. There are several other Gemeinde Bau nearby which are well worth visiting including Lassalle Hof, Heizmann Hof, Wachauer Hof and the block opposite which has some lovely brick work. I’ll cover these at a later date. They are a good ensemble of Red Vienna and if visited together give a sense of the scale and achievement.

The presence of trees in the streets provides the greenery which was a principle of the early days of Red Vienna planning and design. Ybbsstrasse is a wide street and so there’s air and light too. This is what can be done when space is not seen as a commodity to be utilised for profit.

Again, Prutscher has designed the block to break up the space to avoid monotony. There are trees on both sides of the flats.

Through the use of planting, and the back wall, it’s possible to walk around the courtyard and imagine you are somewhere else altogether. This is a clever arrangement. If you were elderly or with limited mobility, there is a pleasant walk to be had. I’m not sure if the wall was there before the estate? If it was built at the time, the attention to detail with the arches adds to the dreamy quality.

The photograph makes the building appear more dominant in this space than it actually is. To walk around is to achieve a sense of separation from the building. Children can play here and still be generally observed by parents and carers, but so too can children find corners in which to hide and develop their own independent world’s.

Wider Questions

Prutscher was a designer and craft worker of a high quality and yet caught in the compromise that William Morris, Josef Frank and many others found themselves in. What could be the secret to enable the mass of people to enjoy the luxury and comfort that the rich could buy?

The good quality working class housing built in the interwar period in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Hamburg, Zurich, Frankfurt, Reims, Vienna and elsewhere was a huge advance on the slums and private landlord world that dominated before 1914.

But it was never as good as the standard middle class housing built in that period. It was generally constrained in its size because costs were a key issue. There is a great debate about ‘form following function’ and so on. But in reality, for large amounts of working class housing, form follows money. The housing of Red Vienna is extraordinary in that money-power does not appear to be the determining factor. But money was still a constraint.

And in Vienna, the whole of the house building programme was held in check not just by cost but by the political imbalance between the socialist city and the countryside dominated by the Christian Socials and their increasingly fascist allies. A deeper contradiction was identified by Manfred Tafuri as that between the reformist politics of the social democracy and what were really revolutionary ambitions in its housing and welfare programme.

None of this can be resolved while production is dominated by the power of capital and its greedy self-interest of maintaining its own expansion above all else. And it is the ownership of capital as private property which splits industrial society into two main classes. So long as that continues there cannot be universal interests, let alone a univeral realisation of housing needs.

If…if….if…..the Russian Revolution had been joined by thorough going revolutions in Germany, Hungary, Slovakia and Austria, then much of Europe would have been pulled significantly to the left in the 1920s (instead, much of Europe was pulled to the right).

There were certainly those who for a few brief weeks thought world socialist revolution possible. If that had happened then the power of capital could have been broken. In which case, all housing would have expanded in size, luxury, quality and style.

In that world, Prutscher would not have just been an architect of working class housing, he would have been a universal architect who could have realised his interior design and architecture on a mass scale too.

Whole new schools of art, architecture and design would have formed. Without the need to constantly waste labour power on the production of capital, and the enormous production of waste within capitalism, work could become an activity of liberation and art and craft.

Automate all boring work, use human labour to create objects of great beauty and originality. Imagine how fabulous and amazing such a world would look. Perhaps that will happen one day. If so, books relating to Prutscher will be on many a shelf, his designs brought into existence, his ideas explored, his quality surpassed. We live in a great accumulation of life. Surely the ambition should be, not to destroy, but to add to that?

You must be logged in to post a comment.