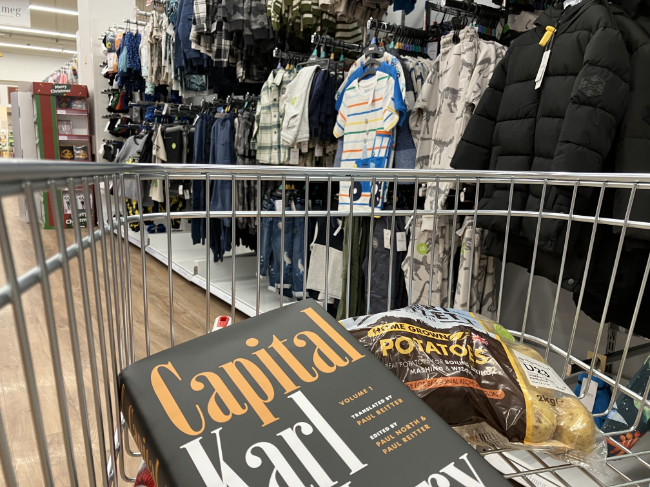

The more Marx is bought to earth, the more fascinating his ideas become. By earth, I mean the local area in which I live. If Marx is relevant to this somewhat shabby and run down urban area then his ideas can be scaled up to a global level. Marx had a lot of theories and most of them don’t concern us here. What he thought of Palmerston, free trade and Russian imperialism we can leave for another day. The new edition of Capital arrived and I want to read it in a way that I could visualise around me what Marx was trying to say.

The very first paragraph of the first chapter of volume 1 of Capital begins:

“The wealth of societies dominated by the capitalist mode of production appears in the form of an ‘enormous accumulation of commodities’. The individual commodity appears as the elementary form of that wealth. Hence our investigation begins by analysing the commodity”.

Marx explains how the physical qualities of the commodity determine its use. And how commodities can be measured and exhanged (let’s leave the theory of money and surplus value to another day).

He then moves into abstractions. How can it be that this physical object of the commodity can have exchange-value? Where is this exchange value? It is not part of the physical properties of the object, but to the capitalist it is the most important aspect.

These opening chapters are demanding reading, but once the concepts are grasped, the world will never look the same again. And if you get lost in the ideas, a walk round the local shops will help to clear the brain.

Marx wrote Capital between 1855 and 1867, the middle years of the nineteenth century. The historical examples of the changes in the English countryside and the origins of the factory districts in the north of England do give the book a dated feel. But the ideas…the ideas in general are so alive.

At times it feels as if Marx is struggling with Information Theory, something that won’t really be developed until the 1940s. I detect Vint Ceft and Einstein in some of his passages. And with hindsight (that so valuable of tools) everyone now knows that he developed ‘historical materialism’ (along with Engels). But this was not at all apparent when the book was first published.

I’m reading the book slowly to carefully look for words and concepts. Marx uses the term ‘social-metabolizing’ and that alone could be a chapter. Just that one term can lead the reader into whole new spheres of thinking.

But will Marx still be relevant when taken from the study and academy and into the streets and shops and factories and warehouses and …dare I ask, the supermarket?

Some of Marx’s writing is convoluted and dense, layered with so many sources and ideas that it can be difficult to pull sense out of the words and sentences. And then suddenly he looks up from his writing desk, draws breath and puts down on the manuscript page:

‘What the capitalist wants…is the movement of ceaseless profit making’

Does Marx’s idea that the accumulation of capital is in fact the ‘accumulation of labour’, apply here? On these shelves? Well I don’t see how else this can be explained other than as an accumulation of labour. And the capitalist isn’t selling hair dyes because the capitalists is bothered by the colour of people’s hair. The capitalist wants to make money. Hair dye is just a good a way of doing this as jars of marmalade or container ships or office blocks or bicycles.

If nothing else reading Marx has made me wonder how the owners of supermarkets explain all this? What do they think is really going on?

“It is only within capitalism that this accumulated labour becomes capital; that is, property which is owned privately rather being in the public domain for everyone who needs it to use it”.

I think that helps to explain the supermarket rather well.

There is more here too. The visual identity of commodities, of consumerism, of what might be called ‘the creative commodity’.

Each individual unique commodity is a replica of a primary, individual object. The bottles of liquid detergents and fabric conditioners started as a unique design. Then as prototype and then into production. The colours of the bottles, the logos, the branding, the advertising; these are all part of the process of turning the commodity into a commodity-image-object. These surround us. These help to form how we see the world, these help to create a social reality.

There are so many billions of these commodities that it can appear that they are the social reality. We all see them and are surrounded by them so they appear to be some sort of universal truth, an natural state of affairs, they are everywhere and dominate our visual experience. Everyone goes shopping; how many people visit natural places on a regular basis?

The production of these commodities however is dispersed, often hidden, in countries where it’s difficult to travel, in factory districts a long way out of town. The intensity of the division of labour means that few actually see production as a physical totality. The actual form of the commodity is only apparent at its final moment of creation.

It is also possible within the supermarket to see how many different types of labour have been used.

Harvesting, weaving, baking, food processing, hammering, lifting, digging, metal working, glass making, computer programming, writing and many more types of human labour have all been applied to the production of the objects on these shelves.

And at some point in the process of production, the raw material has absorbed direct human labour power and the accumulated labour-power embodied in machinery and tools. And this has all been possible through the use of electrical power, the use of water and gases and chemicals and increasingly the application of computing power.

All of this impacts upon each and every price and it seems extraordinary that so many items can be bought so cheaply. Such is the impact of the use of a global means of production, the marshalling of the forces of labour in an intense division and the discovery and application of the power of nature through science.

Through a global network of distribution involving ships, ports, railway networks, lorries and vans, inventory and logistics software the commodity arrives at its point of sale. Here it is at rest, until someone buys it. The ambition of the commodity is almost done; all that remains is its transformation into money, then back into the accumulation of capital.

I have a shopping list and yet buy things I hadn’t intended to. Chocolates, peanut butter, cheesecake (on special offer). An elderly woman who is stooped over a stroller asks me if I can help her. ‘How much are these?’ she says, pointing to bags of white chocolate snowball sweets.

‘It’s two packets for three pounds’ I explain.

‘I’ll think about it’, she says, looking up at me with sparkling eyes and smiling. Her whispy grey hair frames her face, full of life.

I wait at the check out for a minute or so although it feels like glacial time. And then it’s my turn and the cashier asks how I am and do I have a store card and stuff like that.

‘Have you got your own bag?’ he asks.

‘Yes thanks’, and then I add, ‘it’s not a bag I need so much for my shopping as some help in paying for it’.

He laughs at this.

‘Everything goes up apart from my wages’.

There’s a lot of poor people around here and lonelines and depression and alcohol and drug problems and these acts of kindness and fraternity and friendliness are of immense value. Much greater value than exchange-values.

The creation of solidarity is also an act of production and we need to add to its accumulated mass and speed up the process of its circulation anyway we can.

You must be logged in to post a comment.