The only part of Capital to be published in Marx’s lifetime was volume one. It first came into being in Hamburg in 1867. Throughout the book Marx confidently asserts that ‘more of this will appear in volume two’, ‘this argument will continue in volume three’ and so on. But those later volumes were not finalised by Marx himself. After his death in 1883 they were put together over a period of several years by Friedrich Engels and Marx’s daughter Eleanor.

But let’s imagine for a moment that all three volumes were published in Marx’s lifetime. And that, say in 1877, a publisher decided to put them out as a complete set. A three volume set in that year might have appeared with embossed gold lettering, and there might have been a picture of Marx, protected by an opaque sheet of paper in the opening, inner pages. But there would have been no picture of Marx on the front covers.

But the look and feel of books has changed a lot since then. The development of printing technologies, new processes, advances in typography and the introduction of colour inks have all changed the characteristics of covers, paper and design. That’s how we’ve arrived at the book design of today.

Now let us continue with this daydream of a day in 1877 when the Marx family were living in Maitland Park Road in Kentish Town. Engels had become established nearby in Regent’s Park Road and was a daily visitor. He had come round early that morning. Eleanor’s pet dog Whiskey is barking as the first edition of the books, in a complete set, is delivered. There is a general hullaballoo as the family helps itself to breakfast, half drunk cups of coffee, a cat licking melted butter from a crust of toast. Marx and Engels at the table that serves as a focal point for the family business, daily gossip and updates, and another place for Marx to accumulate books, notes, manuscripts and ideas.

A pot of jam is moved and some crumbs brushed away and the parcel is set on the table. A collection of journals are scooped up and temporarily put on an armchair once another cat has been shooed from its indolent observation of the day.

‘Look what’s arrived!’ Jenny Marx says, untying the string. It’s better than cutting it with a knife as then the string can be used again. And as she unwraps the paper, let’s pretend that there has been a tear in the space-time continuum and the volumes that have arrived are the ones illustrated at the top of this page.

She tries not to laugh as the photographs of Marx are revealed. Engels takes a deep breath and hides behind a newspaper, aware of how tetchy Marx can be at times. By chance, all three daughters, Jennychen, Laura and Eleanor are present, and they are less restrained.

‘Look at papa!’

‘How serious he is!’

‘I am Herr Doktor Karl Marx of bad philosophy!

‘I say down with the bourgeoisie!

‘Too much gin! He’s got another hang over!’

The teasing would go on for weeks. And rightly so. There is nothing in any of the biographical details of Marx, recorded by his wife and daughters, that Marx craved celebrity. There is nothing in the observations by Wilhelm Liebknecht or Friedrich Engels or countless others which suggested Marx had any interest in himself becoming famous. It was the ideas that mattered. They mattered in the mid nineteenth century and they matter today.

Now let’s move to the 1970s when this three volume Penguin edition of Capital was actually published. The covers strike me as odd. The books are not autobiographical or biographical. They are not about Marx the man. What is the exact purpose of this design? How does it relate to what Marx sets out to explain?

This first volume is about the centrality of human labour to the whole dynamic of society, of the development of commodity production, of money and capital as processes determined by capitalist relations of production. It includes coverage of the production of surplus value, the role of money as a universal equivalent and the relation of production to value, money and price.

Now I am not suggesting that parts of this are particularly easy to represent in images or graphical design. Some of the concepts, even when written down and explained from a variety of perspectives, are not immediate and require thought and study. But on the other hand, once you start looking, you can see stuff about prices and wages and profits and capitalist relations of production everywhere you look.

This is not all. These are no ordinary books. Throughout, Marx illustrates his arguments with ideas from Greek philosophy, events from Roman history, the dramas of Shakespeare, the empirical data of the development of factory production, quotations from factory inspectors, fragments of speeches from factory workers, the impact of enclosures in Britain, the death by starvations of thousands of weavers, their industry destroyed by mechanisation. Metaphors are turned around on the pages to take the reader from the physical actuality of the written page into the nebulous imagination of the reader’s own mind.

In places, volume one is an unbalanced book; there are pages about the conditions of cottagers in a dozen English counties but little if anything about the scale of construction in London in the mid-nineteenth century. There are sarcastic asides at figures who would have been familiar to nineteenth century audiences but are now unknown to all but a few historians. I find the section on the transition from the middle ages to capitalist production to be unconvincing. But there is an interesting outline of the development of capitalism in Italy and the Low Countries in the fourteenth century, and the emergence of a class that can be described as the bourgeoisie can be clearly discerned.

Paintings (all are in the Louvre), clockwise from the man holding a blue book:

Giovanni Giorgio Trissino, Hommes de Lettres, Vincenzo Cateno – 1500-25

Femme dé nudée vue en buste, anon – 1500-40

Portrait d’homme – Titian – 1500-25

Portrait d’homme – anon – 1500-50

Portrait de femme, La Belle Ferroniere – anon – 1500-10

There are surprisingly detailed descriptions of individual pieces of technology, but not a general theory of technology. There are certainly elements of Marx’s character throughout the writing; after all, it is his voice and tone, but these are still not books about Karl Marx.

In many ways in fact, volume one is a book about England. Edward VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, William Cobbett, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, London, Manchester, Nottinghamshire, Birmingham are part of the many references to people, time and place; of England past and present.

Marx quotes from John Fielden who describes the horrors that the developing and burgeoning factory system inflicts on the population, particularly children, who are flogged and beaten, half-starved (and certainly sexually assaulted although this is not mentioned). Fielden writes:

‘The beautiful and romantic valleys of Derbyshire, Nottingham and Lancashire, secluded from the public eye, became the dismal solitudes of torture, and many a murder…’

In some ways, a picture of the English countryside would make a surprising, but more sensuous and thought provoking cover. Perhaps putting Constable in the same plane as Marx could help make the point of when and where Marx was writing, and that he had a lot to say about the impact of capitalist industrialisation on rural life.

The fields that Constable painted were now full of agriculture workers who were becoming proletarianised, losing ancient rights and customs and subjected to the greed, bullying and aggression of squires and country parsons who were appropriating land that had been held in common since anyone could remember. The labourers fought back in desperate inchoate struggles that ended with hangings, prison and deportations. Marx describes their plight.

Or perhaps the covers could have spoken more to the world of the 1970s when these three volumes were published (1977, 1978 and 1979 respectively). This period was in some ways the peak of a certain phase of capital in Britain; urban landscapes often dominated by large steel works, chemical industries, engineering, large-scale manufacturing, a range of factory types, port infrastructure and mining.

On a global scale, the foundations of the global internet and networked computers was being built. By 1973, the application of science to technology had created TCP/IP (transmission control protocol/ internet protocol) which enabled packet switching of particles of data. An immense revolution in the means of production and communication.

The impact of containerisation and modular cargoes accelerated and transformed the global system of distribution, enabling a widening of the internationalization of production and an intensification of a global division of labour. The general tendencies which Marx had outlined were growing in power, becoming faster and impacting on ever greater areas of production. In this context, photographs of Marx himself seem ever more dated.

Marx does not set out a blueprint for a future socialist society in Capital but he made it very clear that capitalist relations of production are a disaster for large numbers of people. And this isn’t just to do with prices and wages and working conditions, although it is to do with that as well. It’s about how your life-energy is sucked out of your own body and turned into commodities that may or may not be sold and in the process you are turned into an appendage of a great big global system and you work for that system. Rather than that system of global production working for you.

Marx’s theory of liberation isn’t set out in chapter and verse but it’s easily found within his work. He gets to the core of what is produced, how it is produced, why it is produced and in whose interest.

To grasp Marx’s discussion about use-value, exchange value and value is to break the bourgeois ideology in your own head. It creates a profound change in the perception of what you imagined to be the reality of daily life. This is one aspect of the revolutionary character of Marx’s work.

Marx’s theory of liberation isn’t about waiting for some future communist society; it’s about liberating your own consciousness from the endless head-fixing. Encouraging the reader to look beyond the surfaces, to lift up the edge of the carpet of immediate appearances and study what’s underneath among the dust and debris that is usually hidden from sight.

And in the process, Marx encourages us to think deeply and widely about the world around us. The biscuits in the local shops, the lorries that fill the roads, the high rise office blocks that come and go with unsustainable regularity, the shopping centres and growth of the world-wide factory system. And Marx created a practical and operative approach that is elastic enough to enable the core ideas to be scaled up as capital accumulates and expands.

The reader will also realise that it is absurd to suggest Marx distained philosophy. He is a profoundly philosophical thinker. Only it’s a philosophy of everyday objects, not of the mind working in isolation from the physical practicalities of food and shelter and production. And these everyday objects – and the machine tools and heavy industries that create them – are all initially and primarily created as commodities. And that’s what he starts with, in the very first chapter of the first volume.

The conclusion, and to a certain extent the reader is left to work this out for themselves, is that the whole system of capitalist production of commodities, the whole social tangle of capitalist relations of production, the whole creation of use-value, exchange value and value needs to all be brought to an end.

This was an extraordinary achievement and it is degraded by suggesting that Marx had any ambition to have his profile on postage stamps, his body turned into grotesque ‘socialist-realist’ statues or his mug shot carried around on banners, often on military parades complete with nuclear missiles.

And there is something grossly distasteful about any political practice that insists (with the aid of police truncheons or party apparatchiks) that one must ‘follow leaders’, whoever they might be. Or to imply that some authoritarian half-wit has a licence to dictate and imprison because they have a badge of Marx on the lapel of a well-tailored jacket.

Marx wanted people to grasp his ideas in order to get rid of capitalist production. He never wanted to be some sort of weird secular saint (and he certainly didn’t have a saintly disposition). And there is something very wrong when the dialectical-reality-philosophy of Marx is turned into dogma, sermonizing and religious canon.

There is also something off-key when people on the left think that pictures of a man from the mid-nineteenth century is going to have any appeal to large numbers of people in the twenty-first. It makes the left look dated, lacking real-life fire-brands (partly true), stuck in the past and promoting images which are out of kilter with the current phase of the Society of the Spectacle.

There is something not right with all of this and I personally think a line should be drawn under it. In fact, that line should have been drawn a long time ago. All of the regimes that have ever gone in for this stuff have been horrible. Thought police, prison camps, physical battering of political opponents, long hours of boring work for the masses, caviar and chips for the political elites. No, down with it all.

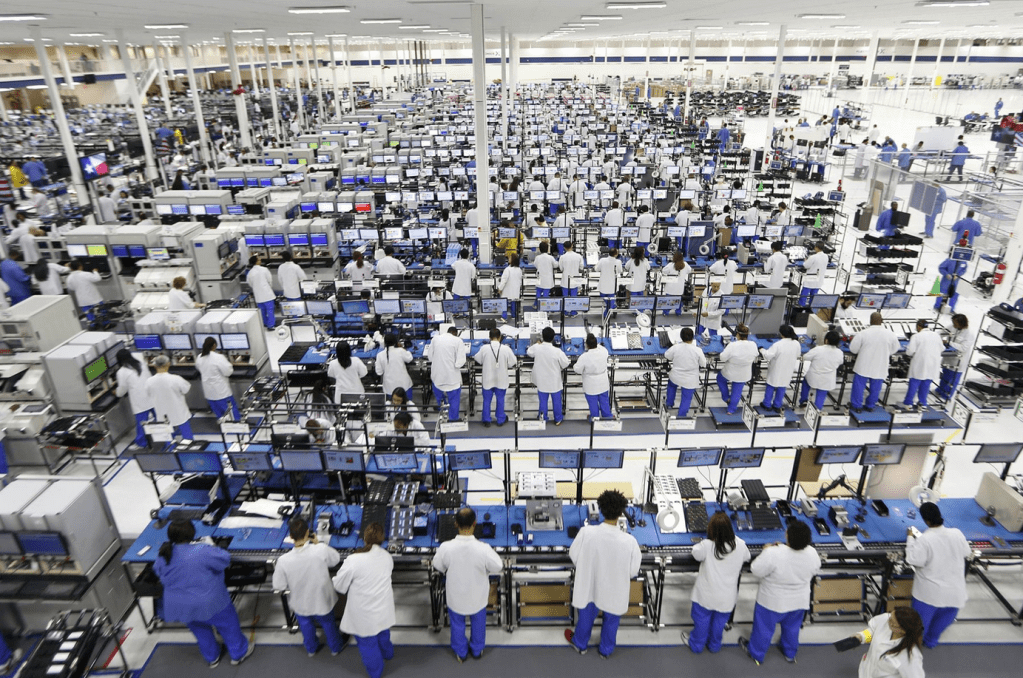

And if we need images, how about office blocks, containerships, machines that make microchips, hand production in the Mumbai slums, the giant Foxconn factories, migrant (often classified as ‘illegal’) labour in the fields of North America and England, drivers on the conveyor belts of Europe’s motorways, child miners digging out rare earth metals, skilled workers producing aircraft and MRI machines. Might there be something in that imagery that workers in the 21st century could see themselves in?

If Marx’s ideas are still relevant, and I would argue they are, how are they made attractive and accessible to people today?

Engels is smoking a cigar and still pretending to read the newspaper and trying not to keep looking at Marx from the corner of his eye. Marx is secretly very pleased with his books but embarrased at seeing his own countenance staring back at him.

Eleanor turns volume one over in her hands. ‘This would look better with a picture of a typewriter on the cover’, she says, ‘not you!’ and laughs.

And then she playfully and lightly taps the book on Marx’s head.

You must be logged in to post a comment.