…Hegel came too

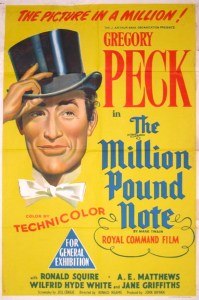

In the film The Million Pound Note Gregory Peck plays the character of the American sailor Henry Adams. He has been blown off course in his schooner, picked up in the Atlantic and ends up in London penniless. Two eccentric brothers, Oliver and Roderick Montpelier see him in the street (he is trying to pick up an apple from the pavement as he’s hungry) and invite him in to their grand Mayfair house.

He is given an envelope which he is told not to open until 2pm on a certain day. When he does so he discovers it contains a one million pound note. The brothers have a bet; Oliver wagers that the mere presence of this piece of paper – for that’s really what it physically is – will enable all sorts of things to happen, and it won’t actually need to be spent.

The Million Pound Note

As it becomes known that Henry Adams possesses this object his fortunes dramatically change. The luxury suite in the best hotel, a new valet, his own tailor in Savile Row, invitations to mingle with the aristocracy (still in the period of opulent imperialism, it is after all, 1903). Even his name now has added value. Just its mention helps secure a fortune in a gold mine.

The film is based on the story The Million Pound Bank Note by Mark Twain and it delivers wit and sharp social observation. But will the note need to be cashed? I’ll leave you to watch the film to discover.

In a light hearted way the film makes a telling point about the social character and the social power of money and gently asks the question: what exactly is money?

Most of the time, the main concern many people have about money is the quantity; how much of it do they have. And when money is an expression of prices; ‘how much does it cost?’

But money is much more than an expression of price (although it is that as well). It is multi-faceted, with multiple meanings, definitions and characteristics. It is something which is deeply engrained into the social relations of the modern world and the relations of production and powerfully infuses the human consciousness with its presence.

The keyword money cannot be reduced to a one-line definition. Marx writes a great many words in Capital explaining, defining, critiquing, analysing and describing money. He writes exhaustively about money; as he does about the commodity, value, exchange-value, surplus-value, capital and more.

He sets out these concepts, pulls them apart, describes their multifaceted characteristics and then puts them partially, and then completely, in relation to other multifaceted concepts. In doing so he creates the multi-dimensional sphere of capital and capitalist relations of production.

There is a uniqueness to Marx’s approach which make it difficult to find analogies. This sphere that he describes, the totality of production dominated by the commodity and capital, governed by capitalist relations of production, lubricated by money, is not analogous with the human body, the universe, the computer, or the mind.

It is more like the repetition and originality and movement of fractal patterns. And describing fractal patterns is no easy task.

This is partly why Capital is such a complex work, bringing together 3,000 years of human history, Aristotle, Ricardo, Hegel, factory workers, land ownership, technical innovations, 20 yards of linen, four gallons of schnapps and much else.

Marx is not only trying to create a language to describe the reality of the sphere of capital but also to find a style which will describe something so strange; so concrete yet so abstract, so moved by hidden forces while seemingly so simple and apparent.

At times Marx’s striving to find the exact words, the voice, the tone to describe all this can almost be sensed on the pages. Dimensions exist which are both in harmony and conflict; historical and contemporary, connected and seemingly random relations, in the same time and space, in a different time and space, opposite and united.

The medium of the printed page feels inadequate to the task of describing the sphere of capital and money, a space in which everything is in movement, swirling, flowing and ebbing, constantly changing, simultaneous growing and shrinking, moving in two opposing directions at the same time. It’s as if Marx needs to bring together political economy and theoretical physics.

This is the realm in which Marx makes his study of money.

Money is a feature of capital, but it is not unique to capital. Neolithic societies used a range of objects to exchange goods with. Some of the first objects that acted as money – or a means of exchange – included cattle, beads, axes, stones, gold, slaves.

Money suggests in the first place some sort of surplus. One group having more of certain objects than they can directly consume. A good harvest, a fertile herd, a chance finding of a rich deposit of iron or copper.

Initially all exchange was a form of barter; one group exchanging six cattle for 20 axes, another group exchanges 30 rabbit pelts for 2 copper ingots; here the exchange is honey for wheat, there it is turnips for apples, seeds for hemp rope.

The working out of equivalents (how many rabbit pelts could be exchanged for how many axe heads?) would be done through social intercourse. There were no physical measures that could be used. There was no univerally accepted measure of value.

As society developed more objects were produced. Settled farming and the introduction of tools, carpentry, metal working, stone working, weaving, the accumulation of knowledge, the intensification of the division of labour, all helped to increase productivity. At some point, the limits of bartering were reached (not necessarily in all objects at the same time) and also, some objects began to be produced speculatively, for the market, as commodities.

Once this stage is reached, two things happen. Bartering is now longer sufficient; it’s limits have been reached. Bartering becomes a drag, an obstacle, a fetter on the further development of the productive forces. The second is that money begins to emerge in the form of coin, of socially acceptable materials (gold and silver), with recognised markings, sizes and shapes, and eventually weights, and then later, agreed values.

Money slowly developed as the universal means of exchange. One gold coin could now be exchanged for x number of rabbit pelts, y number of copper ingots, z jars of honey.

Let’s leave this broad brush history and jump back into the contemporary world. Now let’s imagine that money had never come into being as the universal equivalent and the means of exchange.

Here comes the lorry from the Heinz factory full of bottles of tomato ketchup. From a different direction, a lorry full of Mrs Elswood gherkins. A van load of Spontex sponges, another lorry, this time full of Warburton’s seeded bread, and then another stacked up with bottles of Fairy Liquid.

The owners of these commodities want to sell them. But not necessarily to each other. What use is it to Proctor & Gamble (the owners of Fairy Liquid) to exchange a 1,000 bottles of washing up liquid for 1,000 bottles of tomato ketchup (owned by Heinz)?

They are all back to where they started. They are still the owners of commodities but they haven’t sold them. Which means they haven’t realised any value, and so, no profit. They are capitalists after all and it’s profit which gets them out of bed each day.

That’s the capitalist perspective. But what about the consumer? I don’t go to the supermarket as a hobby. I go because I need to eat and buy things for house such as light bulbs and cleaners.

In my basket I have potatoes, a lemon, a pot of parsley, a pack of butter, four notebooks, a jar of gherkins, two packets of scallops, a bottle of tomato ketchup, a loaf of bread. Most of this is for my supper. I need to eat, as do we all.

[We could expand upon all this by considering where all these products originated from, the inputs of capital (raw materials, labour and technology) required to make them in the first place and how much socially necessary labour time they each contain. But let’s leave that for another day]

It would take an age and possibly a lot of argument to work out how each of the items in my basket could be bartered with other things. And what would I barter with? What if Morrisons wouldn’t accept Trotsky’s book on Permanent Revolution in exchange?

And it gets even more complicated. That’s just a few goods in my basket to sort out exchange with. It is estimated that an ‘average’ supermarket may have up to 30,000 – 50,000 different types of commodity-image-objects (known in the retail industry as stock keeping units). How could the owners of all these different things barter with each other? It would be impossible.

And how could anyone work out how many bottles of Fairy Liquid are worth some many pots of parsley? Or how many potatoes would be needed to exchange with a packet of four sponges? Never mind the seller, what is the consumer to do? Shopping would take up most of the buyer’s waking hours.

Money smooths this all over. The owners of the commodity-image-objects are the sellers. They sell to the supermarket for money. The supermarket sells to the consumer for cash. The consumer, the buyer, pays with cash.

Many consumers are workers. They sell the one commodity they own, their labour power, and for this they are paid in money. Commodities dominate both production and consumption.

And so many complex circuits move along together, all made possible because all exchange is with money. And money is the universal equivalent. A measure of value, a store of value, a carrier of value, and means for value to be exchanged.

The commodity-image-objects are stacked on the shelves and decorated with price tags, the visual expressions of their money value.

Everyone knows where they are. Each buyer and seller and seller and buyer, regardless of where they are in the chains of production and consumption, knows their place (and their price), and the limitations and possibilities.

[As a side note, It also helps both the buyers and sellers that every infant is quickly socialised into this overall dynamic. Just consider how many adverts there are on children’s television, outside schools, on the internet, bus stops, inside shopping centres (which many children are introduced to at an early age); and how the importance of brands and logos is drummed into children’s heads on a daily basis].

In the illustration below, a £20 note is being exchanged for a bottle of tomatto ketchup, a bottle of Fairy liquid, a jar of Mrs Elswood gherkins, a pot of parsley, a packet of scallops, a notebook, and a lemon. In fact, the £20 is being transformed into these goods; or that’s how it can appear.

Water to wine. That sort of thing.

In the second illustration (below) a range of commodity-image-objects (our friends the tomato sauce, lemon, scallops, parsley, sponges, notebook, potatoes) are exchanged for a £20 note. This is the seller’s side of the exchange. Here the commodity-image-objects are being transformed into money.

And money is so flexible that it is possible to buy almost anything (apart from love apparently).

Those who posses large amounts.of money can buy great piles of raw materials; metal ores, animal skins, wheat, oil, coffee beans, timber, sand; even 20 yards of linen.

They can buy that most precious commodity of all; human labour-power.

They can secure loans to built factories and machines.

By adding raw materials, technical infrastructure (buildings and machines) and human labour together they can produce more commodities. And from this, generate more money and accumulate capital and make profits and become rich and powerful.

It’s been a busy 20 minutes in the supermarket and I take my basket to pay for my shopping; using money of course (it doesn’t matter whether it’s cash or card, the process is the same).

I usually go to the cashiers but on this occasion I use the self-checkout. I realise there is opposition to these technologies in relation to ‘jobs’. But this has to be seen in a wider view. Cashier work is tiring, monotonous, low paid and can be stressful.

Couldn’t this buying and selling process be automated? And cashiers given a guaranteed universal social income? And on a nice spring day, instead of moving thousands of stock keeping units along a conveyor belt, walk along the seashore or meet a friend in the park, or sit at home with a cup of tea and slice of cake reading a good book?

What exactly is life all about, and what is it in reality and what should it be? A supermarket is as good a place to ask these questions as the academy; in some ways, a better field of study.

I put my shopping in what I think is the basket area and my bag in the bagging area. The attendant comes over to explain I have done this the wrong way round. She has a saintly patience. This is part of her sensory labour-power. She is selling this as a commodity. In the process she is selling her consciousness and sense of self, her very person. But what could be more precious to her than that? And yet she is coerced to sell her very being for a trifling amount.

I slowly turn each commodity-image-object to find the bar code. The next time you put your shopping past a cashier notice how quickly they do this, and observe how much they are repetitively moving their hands and arms, eyes moving from commodity-image-object to the screen, back to the conveyor belt, back to the screen, a glance to see what the other customers are doing, a quick hello to a friend. On and on, hour after hour.

This check out is one of millions of global nodes of data processing. Billions of data points per second, data being analysed, aggregated, collated. Merged with hundreds and thousands of other data streams, personal and anonymised. Internet browsing history, bank card use, online and physical shopping, travel cards, phone apps, train tickets, movements across borders, the number of steps, the number of hours spent looking at screens, cash machine withdrawals. Data warehouses, customer relationship management software, cloud computing, tracking, tracking, tracking.

The screen on the automatic check out needs confirmation that I have bought my own bags. But only the shop assistant can do this. She is at the far end of the two banks of tills. She has to walk the distance again and again.

‘You do a lot of walking’, I say when she swipes a card to let me proceed.

‘Yes, I do a lot of steps’, she says. She raises her eyebrows as she states this. This slight movement communicate a great deal more than her words.

In these moments I have been buying, and the supermarket has been acting as a seller on behalf of others; an intermediary, part of the process of distribution.

I must pay with card or cash. What I cannot do is barter. At this point I cannot demand that the supermarket accepts 20 boxes of Weetabix as payment. Should they do so, that would be a physical exchange; it would not be buying and selling.

And so another function of money is revealed. It is fundamental to the process of buying and selling.

It appears so simple. So obvious. Axiomatic. Natural. Part of the natural world. Unchangable.

And this me, is what makes Marx so interesting. He takes the everyday and pulls it apart to reveal the most extraordinary mysteries.

Buying and selling, as Marx points out, are seperate and yet fundamentally entwined events. Selling is a different process to buying; but they cannot exist without the other. And although they are oppositions, they are bound in a never ending unity.

And as the £20 note disappears into a slot in the machine, the goods become mine. In this unity of opposites, the £20 note is transformed into sauce, pickles, sponges, scallops, notebooks, bread, parsley and potatoes. A lovely Hegelian dialectic dances across the bagging area and the electronic voice from the automatic till says, with a German accent of the early nineteenth century, ‘I told you so’.

But it doesn’t stop there. No one said taking Hegel to Morrisons would be easy. The practical-concrete, abstraction mysticism continues.

This is not just an exchange of a £20 for the objects in the basket. It is also an exchange of value. The value represent in the £20 note and the value of the commodity-image-objects is realised.

Money has enabled this process. But this is a strange metaphysical development. For if the commodity-image-objects are dissected, pulled apart, reversed engineered, filled with dyes, x-rayed, boiled and distilled, not an atom of value will be found.

For all the concrete character of the £20 note and the very real presence of the items in my basket, the most important part of this exchange for the seller, that is the owners of commodities, the owners of capital, is the realisation of something that doesn’t seem to physically exist. And that value now floats off in its own independent existence.

Are we ready for yet more strangeness?

The commodity-image-objects are now in my shopping bags. But what’s happened to the £20 which went into the slot in the machine? Well lets assume that someone comes around and empties the machine at 4pm. There’s a shortage of £20 notes at till three, so my £20 note is added to the float.

A customer comes along at 4.20pm and receives that £20 note as part of their change. They go to Boots on the way home to buy some aspirins. All this talk of value has given them a headache. And so the £20 note wanders around the town. Each time helping to realise value without ever seemingly to exhaust itself.

The commodities now drop out of circulation. I will turn the potatoes into chips and fry the scallops in butter with garlic and parsley. A large dollop of tomato ketchup will be added to the plate. The sponges and Fairy liquid will be used to do the washing up. These commodities will be directly consumed by myself over a period of time.

I will use my new notebook to make a note today’s experiment; that studying money and looking for value in the supermarket has been successfully completed.

And if a small fraction of Marx’s ideas about money and value can be found in my local supermarket, they can be found in every supermarket in the world, without exception.

I check with ChatGPT as to the number of supermarkets in the world. It replies:

“Determining the exact number of supermarkets worldwide is challenging due to varying definitions and the dynamic nature of the retail industry. However, insights from major retailers can provide a sense of scale:

Walmart: operates over 10,750 stores across 19 countries

Carrefour: 3,842 supermarkets globally, the majority in Europe

SPAR: This Dutch multinational operates 13,623 stores in 48 countries.

Lidl: approximately 12,200 stores across multiple countries

Morrisons: approximately 500 supermarkets and around 1,600 convenience stores”

This suggests immense amounts of capital investment in buildings, infrastructure, technologies and software, millions upon millions of individual commodity-image-objects, thousands upon thousands of people selling their labour-power, great piles of physical money, and an enormous amount of an invisible and weightless abstraction called ‘value’.

I’d very much like to meet Karl Marx in the local Morrisons. And if he wasn’t busy he’d be more than welcome to come and share those chips and scallops.

Footnote:

The next Radical Walk is on Thursday 1st May – London May Day. You don’t need to book – although it’s helpful if you do. You can either book (and pay) via Eventbrite, chip into the hat on the day, or come for free. More details here:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/1264973613129?aff=oddtdtcreator

You must be logged in to post a comment.