Ostheim was discovered by chance, and perhaps the experience was more enjoyable for that. I was going to the REWE supermarket to buy a couple of bottles of beer. I walked along Landhausstrasse and slowly my senses started to pick up that there was something rather attractive here, rather unusual, in the local streets.

I’m still trying to piece together the history of public housing in Germany and am familiar with siedlung (estates) in Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Karlsruhe. This was different. All red and yellow brick and fancy ornamentation (but not too much), arts and crafts with a sprinkle of Bohemia. And all on a larger scale than one might see in an English example such as the Dover House Estate (but let’s be clear, that estate is fabulous in its own right).

These moments are interesting because one’s senses start to work overtime, partly in collaboration and partly in opposition to each other. The senses send certain messages but the brain can’t properly process them. One’s theory and practice are temporarily unaligned. The messages are out of sorts with ‘expectations’ and ‘experience’. The built in commentary in the head has stopped making sense.

It wasn’t what I might have expected in Stuttgart and at first I couldn’t properly understand it. Which is where walking up and down and round and round the streets comes all into its own. Helped by much sitting and observation and where possible stopping people in the streets for informal vox-pop.

I walked around some more the next day, still curious as to what this was all about. That evening, I got to work on some desktop research.

Stuttgart, like all German cities, grew enormously in size and speed during the latter part of the nineteenth century. It’s said that Germany was slow to industrialise, but when critical masses of capital were accumulated, the growth of factory and industrialised production expanded rapidly. The city had a population of 90,000 in 1870 and that had grown to 250,000 by 1905.

The independent German states were unified between 1866 and 1870. It’s worth remembering that the whole Alsace region became part of the German Empire in 1871 following the Franco-Prussian war. It became part of France again after the First World War.

Alsace is a rich area and this expansion fitted the general playbook of global and European imperialism and Empire building of the time.

Industrialisation and imperialism always help to form and develop their own dynamic oppositions; workers’ movements, often with socialist and anarchist tendencies, and struggles for national and regional independence.

In Germany, the worker’s movement, Marxist intellectuals and socialist reformers developed the large and influential Socialist Workers Party of Germany (SPD – Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands).

The imperialist tensions, the particular accumulations and flows of capital, the competition between individual masses of capital, the competition for raw materials, the aggressive search for markets created bigger and bigger sparks. Eventually one of those sparks landed on the powder kegs of nationalist armed forces and the explosion led to the First World War.

For two long years, imperialism and militarism and nationalism held a death grip on the fate of whole nations of people. Millions died. Hundreds of thousands of houses and buildings were destroyed. Whole libraries of ancient books were destroyed. Cultural collections were blown to pieces.

War created anti-war. The manic organised slaughter of the generals was brought to an end by revolutions in Russia, Germany, Austria and Hungary. The German Empire, the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire disappeared. Maps had to be redrawn. Masses of people relocated. Systems of production re-established.

But this doesn’t really explain these cheerful, solid, intriguing houses in Ostheim.

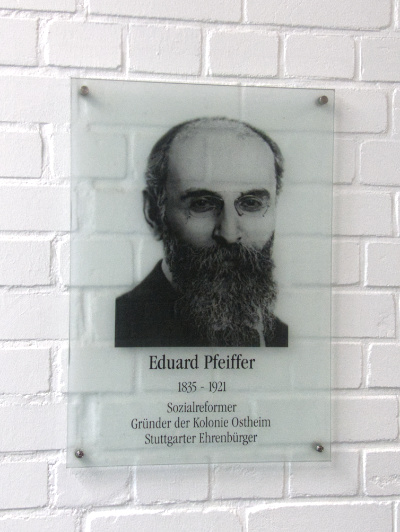

These pre-date 1914 and were the result of the actions of the industrial philanthropist, Eduard Pfeiffer. He had inherited wealth and also worked to increase his wealth, helped along by his marriage to a rich Parisian widow, Julie Benary.

He was a serious scholar and following a trip to England in 1862 became interested in, and influenced by the Cooperative movement. Through this he developed an interest in housing, planning and sanitation issues caused by the rapid growth of population and urban areas. This type of reformist philanthropist could be found all over the industrialising world at this time.

In 1866, Pfeiffer helped to establish ‘The Association for the Welfare of the Working Classes’ (der Verein für das Wohl der arbeitenden Klassen) in Stuttgart. He led this organisation from 1876 to his death in 1921. He contributed his own wealth to the Association, enhanced by contributions and donations from other wealthy patrons.

There was also political power at work here. In 1866, Pfeffier helped to establish the ‘German Party (Württemberg)’, a ‘liberal’ organisation, with industrialists and professionals based in Stuttgart. He became the first Jewish citizen with a seat in the Württemberg Assembly.

Pfeffier was a conscious reformer with ideas set in particular ways. He genuinely believed in improving the conditions of the working classes; as a way to pull them into support for the ways of capital and to innoculate them against communist and socialist ideas. This created that type of philanthropy which is both well-meaning and patronising, summed up in the slogan, ‘cheap housing for little people’. Enjoy this nice housing, but remember who you are.

Four housing projects were completed in all. Siedlung Ostheim, Siedlung Südheim, Siedlung Westheim and Siedlung Ostenau. Siedlung Ostheim is the one I stumbled upon by chance on the way to buy a couple of bottles of beer. (It was excellent beer by the way, just the thing I needed after the train trip from Paris).

This is solid housing and looks well built and maintained (often housing is not well maintained). It’s more bourgeois Bohemian than actual Bohemian with a slightly burger-master air. The historicism is presented in a slightly dogmatic way; this history is not for revision or reinvention. There can be no debate. Turrets, half-timber gables, bay windows, brick work patterns and dare I say, a slight gloominess, express something that still has a tinge of Kaiser and Empire.

Having said that, the individualism of the houses provides grace and charm and there are unexpected alleyways and nice arrangements of corners and angles that provide a lived-in and intimate feel.

There were 1300 apartments in all, sometimes two or three in each building. In Neuffenstrasse, which is central of the development, many of the buildings have small front gardens. Otherwise gardens and green space are at the rear.

The feeling of space is enhanced by the generally wide streets of the surrounding area. Rotenbergstrasse for example, has a central green avenue with trees. This feels luxurious and helps to support the general principles of sunlight, air and space.

The housing was also supported by a range of amenities; the protestant church of St Luke, police station, post office, children’s play areas, nursery, primary school, public library, swimming pool, air and sunbathing pool and three beer gardens. One of those beer garden buildings, the Rechberg, still survives.

The development was designed by the architect Friedrich Gebhardt with individual houses by Karl Heim and Karl Hengerer. It has more the feel of a garden suburb than a garden city; but there’s nothing wrong with that. The area was connected to the Stuttgart tram system in 1901. It takes about ten minutes to get into the city centre, but it didn’t take me more than 20 minutes to walk.

(One evening on the way back from seeing Barry Kosky’s super production of ‘The Magic Flute’ at the Staatsoper (a very enjoyable evening) I tumbled into a back street pub which was great fun).

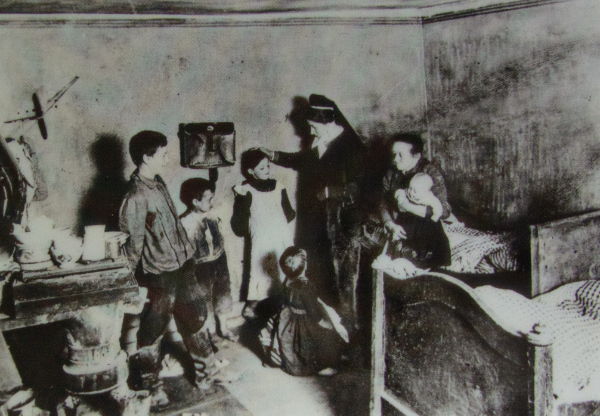

German officials, like those in many countries which industrialised rapidly, wanted statistics about what was actually going on in urban areas. They also wanted regulation in order to control the spread of infectious diseases (which had no regard for class distinctions) and municipal-bureaucratic control in urban areas instead of festering proletarian discontentment with hints of class rebellion.

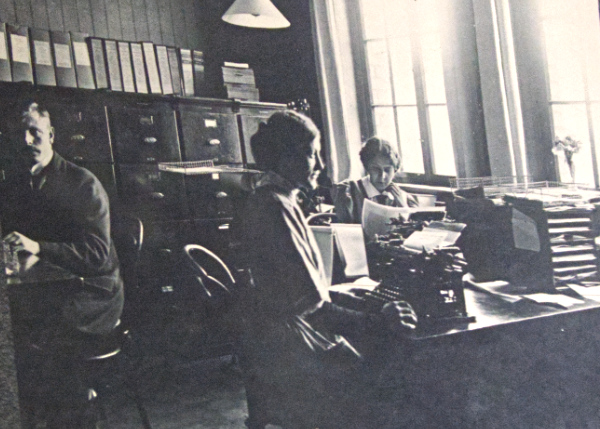

In 1901, a Municipal Renting Agency was established in Stuttgart which provided its services for free. In the same year a survey was carried out across the city which discovered over 15,000 overcrowded, unsanitary dwellings. A substantial mass of housing was expensive and of poor quality. High rents led to overcrowding as groups of poor people shared space in order to spread the costs.

Part of its remit was to have a monthly update as to what was happening with regard to housing across the city. This included details of new housing, refurbishment, planned building, the number of dwellings available to let, the number of rooms for rent, which floors these were on, and geographical location.

It was a legal requirement for all those involved in building and renting to complete the relevant forms. These were simple and straightforward but captured a great deal of useful information. When a building was rented out, the landlord had to inform the agency within three days. The agency also provided free information to renters and acted as an arbiter in disputes between landlords and tenants.

All of this work was supported by the Dwellings Inspections Department. This organisation created a set of regulations which it actively enforced. Every room, including bed rooms, bath rooms and kitchens had to have at least one window ‘of such size as to allow sufficient light and air’.

Regulation 5 stated that every dwelling house had to have a sufficient number of toilets. Regulation 6 stated that damp bedrooms and damp living rooms would not be tolearted.

All the poorer dwellings were to be inspected at least once a year, and any ‘dubious’ dwellings, more frequently.

The housing of the Ostheim estate however was never intended for the poorest classes of the city population. Records of the time reveal that the inhabitants of the estate included carpenters, locksmiths, typesetters, a sub-head of a post office and railway officials. Skilled workers, administrators and managers.

Pfieffer’s intention included some deliberate social engineering. Provide nice bourgeois surroundings for a layer of skilled workers and they will vote for bourgoise parties. It would be fascinating to know what individuals did vote for but across the Ostheim district as a whole, strong support emerged for socialism.

A Social-Democratic federation formed in the area in 1893 and quickly established a voting base of between 70 – 80 percent of the voters. Social democracy thrived in the area. Local events mirrored the greater national events that took place in Germany as the First World War ended. Revolution, shootings, disturbance and riotious protests in the local streets. The Ostendplatz became the established meeting point for demonstrations and there are at least two recorded instances of guns being used in the local streets.

All of this was bought to an end with the conquest of political power by the Nazis. Socialists and communists were beaten up, sent to prison and banned from political activity. Torture and murder followed.

Then the Nazis intensified their attack against the Jews. A popular local doctor, Dr Jacob Holzinger committed suicide, along with his wife Selma. They just managed to get their two children, Hermine and Rudi, out of the country before the fascists exerted their violent terror.

There is a lot to see in Ostheim and I wished that I had more time and better resources at my disposal. To properly trace out the history of the area would require time in the Stuttgart archives and of course, discussions with local historians.

Some of the information I gleaned from the internet was incomplete and contradicted what I seemed to find at street level. There is a great deal of knowledge that is not available on the web because it has never been put there in the first place. No amount of AI is going to solve that.

The existing paper records – particulary of land sales, building costs, local authority decision making – may be incomplete, destroyed or inaccessible. These are all issues one finds when trying to do this sort of research.

But I did manage to put something together. As I have so little data, this next section is really more a collection of photographs than a detailed outline. If any reader can add to this, I would really like to hear from you. These are some of the other estates which were built locally in the early 1920s, mainly commissioned by the city of Stuttgart council.

There is a similar style to the public housing. Note the use of shutters but I would really like to know if these were original features or later additions. The housing looks to be of good quality. All of the blocks are well maintained and there are large green courtyards and plenty of play facilities.

Alfredstrasse

The reference I found suggests this was built between 1921 – 23. However, the statue (the third photograph) has the date 1926. But in relation to what?

Schönbühlsiedlung

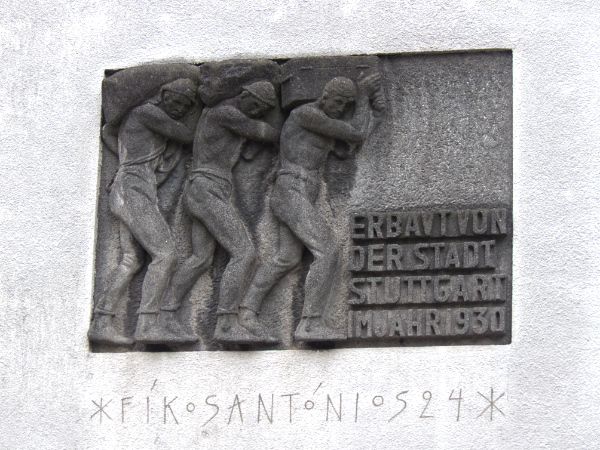

This is the modernist Döckerbau building, part of the Schönbühlsiedlung, built in 1930.

The estate was commissioned by the city of Stuttgart. The architects included Richard Döcker and Ernst Wagner, working in the New Building Style.

All of the buildings originally had flat roofs but, with the exception of the Döckerbau building itself, these were replaced with pitch roofs after the Second World War.

Lehmgrubenstrasse

The first image is what I think is the municipal housing. But there is nothing visible to explain this one way or the other.

Is this part of the original Pfeffier building scheme or something else? It’s on the opposite side of the street.

Rotenbergstrasse siedlung

Rotenbergstrasse housing estate (1919-1920). Built on behalf of the city of Stuttgart by the Sippel & Sprösser architectural group.

It’s this period of house building from 1919 – 1920 in Germany that I want to research further. This was a period of great political turmoil and violent tensions between reform and revolution; and yet house building continued. What impact did this construction have on local and national politics?

The exploration of Ostheim raised far more questions than answers. But surely that’s the point of wandering the streets, looking for clues as to what actually happened in history?

If you have access to JSTOR (much of it’s free, you just need to register), there’s a good article from the American Journal of Sociology from 1904 from where some of this content is derived.

You must be logged in to post a comment.