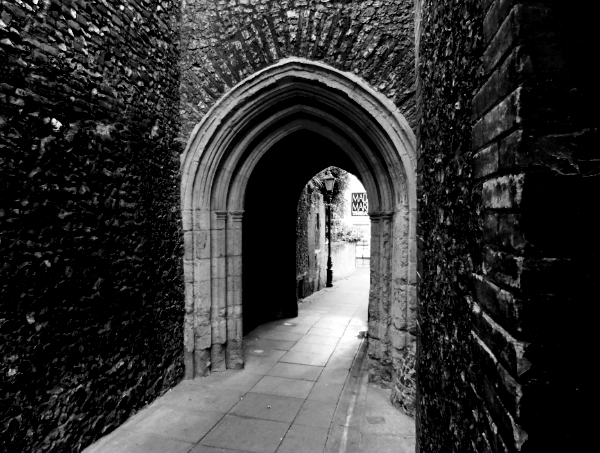

It is an occasion to catch up with oneself, to determine the location of here and now, the recent past; the future is always a shadowy blur. One wishes for magic, illusion, enigma, the mystery of light and shade in both harmony and tension draped over the stone and flint of a medieval church.

Digital networks are too social, and often in intrusive ways, now flooded with 21st century fascism; the wearers of the death mask horror have returned. By degrees they raise their right arm, it is gradually becoming higher and their hand is rigid, fingers pointing to the march that leads to the gas chambers and concentration camps. Is this where life goes to, manic symbols and psychotic brain sludge?

On the train to Norfolk, the medieval churches harmonise with the landscape of winter crops and leafless trees. The infrastructure of high voltage wires and steel pylons, a hydrocarbon economy, silica dependency, petrol addiction. The big white clouds on the horizon are like a mountain range, the fairy tale, the utopia that the world cannot birth.

I read Kevin Lynch’s thought provoking book, The Image of the City, turning pages dense with ideas, and occasionally glancing through the train window at vistas of the countryside and the dominance of capital intensive agriculture. I make notes, keywords and references to explore in city streets.

on a trip, where do you first feel a sense of arrival

thematic concentrations sensuous adaptability

nodes (/ and buildings) may be extrovert or introvert)

Landmarks as an artificial world

good and bad, characteristics

singularity, uniqueness, specialization, clear form (will stand out more), contrast with back

ground…../ foreground + background – Gestalt; definition

space concepts; coherence ambiguous curves

The book is full of multi-faceted picture-words, an anecdote to the one-dimension of the flat screen data streams, creating one-dimensional ideas, one dimensional formulations, orthodoxies; some on the left now play the role of category police, ever watchful eyes for deviation from a-priori thinking.

Marx starts with the commodity; this was conscious and made after great deliberation. He read extensively of Aristotle, Hegel, Plato, Adam Smith, Balzac, Heine, Goethe, Shakespeare before he came to this decision.

I recently spent time in Vienna exploring the Red Vienna period between 1919 and 1933. I visited several Gemeindebauten(community, public, municipal housing), met many people, had fascinating conversations in pubs and in the streets and community centres. People generously gave their time and took me on tours of Karl Marx Hof and Rosenhügel, showed me round an apartment block designed by Hans Prutscher, discussed at length and detail the politics, history and practice of Otto Bauer.

Walks were explored, buildings mapped together, days in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Albertina, Belvedere Palace; endless tramping through the streets. Saturday morning in the Naschmarkt with hot black coffee and croissants, Saturday afternoon in the Sigmund Freud Museum to visit a disturbing exhibition about the destruction of his family by the Nazis. First the humiliation, then the violence, then murder. All recorded in detail with inane letters of property acquisition, swastika stamps and signed off with Heil Hitler.

I worked to a plan, drawing hand-made maps which I edited as I explored. Sometimes I would arrive at a building in a street and discover that the sun in the afternoon created a lot of shadow. The next day I got up early and went back and the sun was now throwing bright light across the facade.

All the research for the walks was memorable, even the day I walked for miles along Handelskai, a main road with a railway line carrying heavy freight trains to the Vienna container port. A mouse ran across the pavement. I just wanted to see one particular building but I had misplaced its location on the map. I was determined to find it.

At the conclusion of this particular piece of field work and immersive observation it came to me that what made Red Vienna so powerful was that those who were in charge at the top, the Reformers and the architects, designers and urban planners, Karl Sietz, the mayor, Hugo Brietner, the Finance Director, Fritz Seigel, the Head of Building Control (and a former building site foreman), Josef Frank, Adolf Loos, Margarete Schutte Lihotzky and many others were either committed socialists or were clearly on the side of the workers.

And the workers themselves had a vested interest in all of this because it was providing better housing and schools and kindergartens and paddling pools and higher standards of living and a range of welfare services that greatly reduced infant mortality and infectious diseases. One afternoon I spoke to community workers at Sturhof and one later explained how he was working with some of the oldest residents on the estate and how they all said how proud they were of all of this.

On the side of the workers. What ever happened to that as an ambition of the reformists?

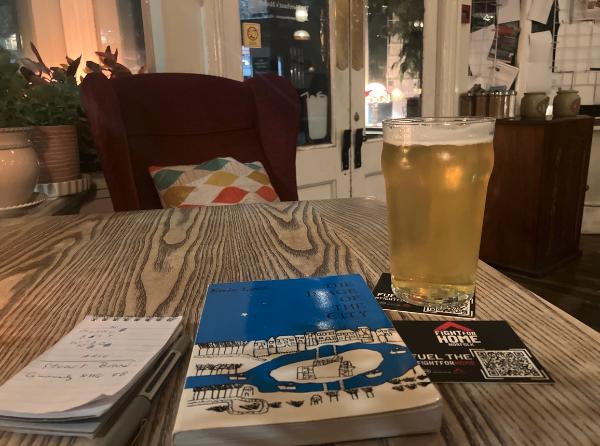

I should have bought the laptop to the pub, but one word notes in a small pad also works. In some ways it’s liberating. There are no distractions. I bought a pile of these notebooks in a sale at Tesco. They are made of good quality paper and it is pleasurable to write upon them with a blue ink pen.

I walked to that Tesco store, the size of an aircraft hanger, early one Saturday morning across recently harvest fields. It was bright inside, full of the packaged pleasures of commodity-image-objects. It’s part of an out of town shopping node and light industrial estate. It’s a concentrated node of capital dominated by motorism. It’s a pseudo-modernism of greyness and without style. As if the Bauhaus had been disinfected; and all that remained was germ-free and antiseptic.

The notebook and pen disconnect me from the digital world and help to ground me and connect into the world of the pub. It encourages a state of half listening, enjoying the sound of the rain on the window, sipping a good pint of hoppy ale, the in-and-out intrusion of Belle and Sebastian from the in-house music system, the eddying and splashing of conversation. The aural sensation of a pub with a convivial atmosphere, the bass guitar of a likeable song, the clink of a bottle as the bar is cleaned and the whoosh of steam as glasses are rinsed.

After a couple of pints, I hear the voice of a friend, ‘might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb’. He always says this at this point in the evening. It’s origins are likely in the Middle Ages. Hanging was the punishment regardless of the age of the animal.

A group of people sat at a table nearby, different voices; they are simultaneously a collective, a group of friends, and individuals. Their conversation creates a mosaic. No voice shouts, none dominate, a woman is knitting and listening at the same time, and looks up and adds a sentence or two.

It is an equitable babble, no words corrode or degrade, the conversation is created and crafted and finely tuned. A broad brush stroke is followed by a delicate detail. A new story is being started and the others listen and hold their glasses of beer and wine and cups of coffee and sup occasionally. It is steady and enjoyable drinking to match the companionship. There is no sense of any interruption. The story will run its course and then others join in and embellish and add decoration and new colours and hues.

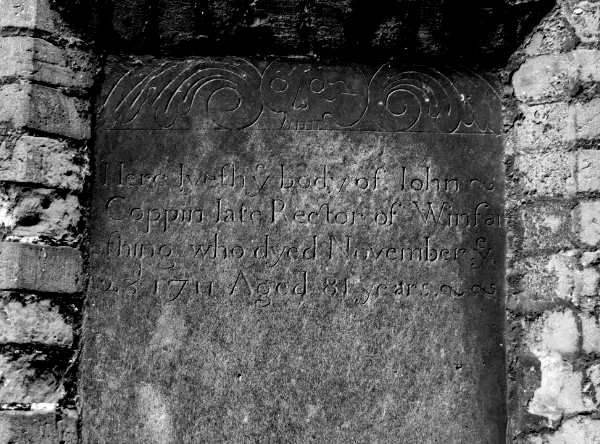

If the display of current fashions is ignored this might be one hundred years ago, or even further in the past, five hundred years ago or more. The past; that curious place which is impossible to reach, but dominates the background, sometime an illness and disease, sometimes a source of inspiration and hope, a place we will never properly understand.

Everything hand-made and local, woollen stockings and hose, leather jerkins and belts, the peasants with their individual knives, icons and imagery placed within local custom and tradition, the women, each with a pair of shears in her belt. To cut cloth, wild herbs, the umbilical cord of life. Local manufacturing, iron and wooden looms, beer from the water of a chalk or gravel stream, clear and sparkly.

A great transformation, industrialisation, electrification, the splitting of the atom, the world connected with TCP/IP, packet data switching, satellites and fibre-optic cables, sub-sea, Atlantic transmission cables, the digitisation of the People’s Republic of China. Synthetic materials, chemical dyes, minerals, elements and rare earth metal extracted, processed, applied through the use of scientific knowledge and precise technical instruments of production.

Mass production.

The intensification of the exploitation of labour at global scale, the expansion of capital, the palaces of steel, glass and concrete in the artificial air, the make-shift hovels in the waste dumps.

The creative arts and craft essence of the proletariat wrenched from mind and limbs through machines and wheels and conveyor belts and keyboards and tools that still needs arms and hands to use them. The very human essence extracted and turned into cheap tricks, glittering baubles and the pointlessness of money-greed. The coercion of production, selling life so cheaply, dreams so hard to buy.

The cadences of conversation. It’s light and airy, then the tone becomes deeper, more serious and then a quip and bubbling laughter.

‘A way of organising that’s melodic’.

I go to the bar to buy another drink. A woman who has just finished her shift asks me what I’m up to. I condense Red Vienna into a sentence or two. She describes attempts to unionise the hospitality sector. Then explains she is from Bulgaria, a student of anthropology and archeology. Her grandfather is still a ‘hard line communist’. I interpret that as Stalinist. We briefly discuss this legacy but where to start? The damage done.

A whole party that claimed allegiance to something called historical materialism and Marxism and dialectics. How can so many people read so much and get everything so wrong? How does a theory of human liberation become turned into a justification for the gulag, a police state and bureaucratic tyranny?

My parting line is that communism cannot be imposed from above. She looks at me with big eye liner eyes.

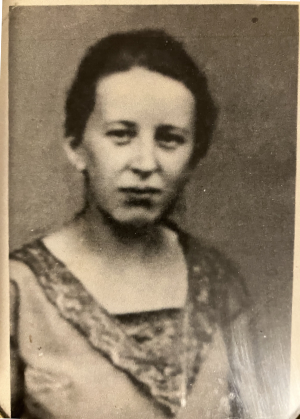

Earlier in the day I’d been to visit my mum who is now in a care home. She was born in the Weimar Republic in 1931 and lived through the Nazi period, the war, the Russian occupation, the mass deportations from Silesia. It is not yet the time to write her story out in full.

On the chest of drawers in her room I notice a photograph of my grandmother. She died in childbirth in 1936.

My grandfather was inconsolable.

Before the fascists, they would dance around the kitchen when a favourite song came on the radio. He would call her ‘Meine Leibe Lotte’. For some reason I have never seen this photograph before. It has immense power and poignancy.

Thoughts form and dissolve. ‘At least once everyday’, a friend would say, ‘you need to have a sense of being alive’.

Through the glass door I can see the pub opposite. It has a security guard standing outside. He looks cold, miserable and alone. He is past the time and age be a security guard. He blows into his hands for half a degree of warmth. It’s performative, he knows, I know, the world knows, it won’t make any difference. When it’s his turn to sit in the corner at the bar he asks the question to those who will listen, ‘how come I built so many houses and yet don’t have anywhere to live?’

I’m thinking about Norwich in 1977 and the excitement of the punk scene. An atmosphere that anything might happen, something for the good, a radical change which would blow away the bad breath and the stale ideas. Cool faces appeared. I can still see some of them now. The first punk I saw was walking near the market, hair swept up in Eraserhead style, grey trousers, an oversized white jumper, carrying a 45rpm in a white paper bag. It was early days, perhaps Anarchy in the UK , New Rose or White Riot. It really did feel like a cultural explosion, heavily saturated with us-and-them politics, of creative socialism from below.

A new conversation from a table in an alcove. This is a different set of notes and tones but they chime together and produce harmonious chords, pleasing harmonies, dialectical counterpoint. The people are playing a game on the table. A woman’s deep laugh drops like a waterfall into the deep pool of her friends voices.

‘Goodbye my friend’, I say to barman who has served me beer all evening. He had explained the origins of the beers on tap, the locations of the breweries (including West Acre), the different types of hops and variations in gravity and taste.

I zip my jacket up and step out into the night. The sleet and the neon lights of a double decker bus moving through the glistening wet of the city. Pavements of dark steel and silver rain water reflect the lights, shimmering and shining, city roofs drip cold slush, puddles distorting the perspective. A medieval church of flint, mortar and clunch, the lead latticed windows absorb light, creating a sense that cannot be touched, a gargoyle stares into the night and terrifies the darkness.

I walk through the streets after an evening in The Merchant’s House.

You must be logged in to post a comment.