This is a walk that takes in a little of Oxford Street, a visit to Selfridges and a meander through parts of Marylebone.

There is much to see in this area and several different walks could be created and each would be unique.

As with all Radical Walks it’s not just the big ticket stuff, it’s the back streets and alleyways, a rarely noticed shop front, cobblestones, forgotten vignettes from newspaper archives, out of print books, trade directories and department store adverts, a gargoyle on a rooftop, a wall of hand made bricks, an ancient doorway and where the beach lies hid beneath the street.

The suggested starting point is St Peter’s Church, Vere Street.

St Peter’s Church, Vere Street

The church now seems out of place surrounded as it is by a new form of corporate capital, offices and dull-witted chain stores. However, when it was built between 1721 – 24 it had an organic connection with the eighteen century houses of the surrounding area, with Cavendish Square and the original street pattern. The design is by James Gibbs, a notable architect of the time.

The church was built as part of the urban expansion west of the City following a trilogy of events. The Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665 – 7, the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666. These calamities followed the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Charles II became king and plague and fire followed. Charles hinted at Catholicism and a closer relationship with the French monarch. His brother James who briefly ruled from 1685 until 1688 secretly converted.

The Whiggish aristocrats plotted and schemed. Papacy had to be defeated and the Protestant ascendancy triumphant. In 1688, the Glorious Revolution; or how a Dutch monarch, who could barely speak English and preferred to converse in French, became a hero to the Loyalists of Northern Ireland.

St Peter’s was originally a private chapel serving the new estate being developed around Cavendish Square by Edward Harley, the 2nd Earl of Oxford and Lady Cavendish Holles. She was a wealthy land owner and their marriage provided him with control over her landholdings and financial assets. One can feel something as to why aristocratic women often came to support the feminist cause.

The chapel is built in red brick in a simple but stylish form. It has a colonial feel. This style was exported to what has become the United States.

During the nineteenth century stained glass by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris was added. The church is currently under-used. It would make a good museum of arts and crafts.

Walk a few steps to Henrietta Place. The CBRE building is in front of you on the opposite side of the road. Turn left into Marylebone Lane. There are two streets here. Take the one on your right (the western one if you’re familiar with the points of the compass). At Oxford Street turn right and then right again into Stratford Place.

Just before you get to Oxford Street note the triangular shaped red brick building. This was originally constructed in 1935 with shops at street level and service flats above. It is now a hotel.

[For a small detour when you get to Oxford Street turn left. Within a few yards you will be at the Disney Store.]

Disney employs over 231,000 people worldwide and has a market capitalization of around $200bn. This represents a significant concentration of capital in what is known as the entertainment industry.

Rather than steel making, office blocks and heavy machinery this form of capital is focused on cartoon mice and ducks, theme parks, film and television, streaming services, merchandise and gaming.

Across the world, curiously out of sight of all the Disney media is a vast hinterland of production. Large factories where workers toil for 70 – 80 hours a week, slums where people sleep next to what they make, mines and farms where child labour is employed. Behind the garish colours, plastic shapes, glitz and glitter, and the commodification of childhood is the commodification of child labour.

Stratford Place

This is one of the few cul-de-sacs in central London and has its origins in aristocratic land power. The large building at the end is Stratford House, built from the 1770s onwards to a neo-classical design by the Scottish architect Robert Adam.

The overall development was by the Hon. Edward Augustus Stratford of Baltinglass County Wicklow. In 1777 he became the second Earl of Aldborough. An Irish peer and Whig politician he sat in both the Irish House of Commons and the British House of Commons between 1759 – 1775.

In the latter he represented Taunton but lost his seat following allegations of bribery. This was not uncommon at the time. Direct bribery still continues in politics and public life today and corruption has now expanded into lobbying, donations and the appointment of peers.

Stratford House is now the Oriental Club. Established in 1824 it moved to this location in 1960. The Oriental Club was set up for those who ruled the British Empire in India and the Orient. British imperial rule was bloody and brutal, destroying existing industries, breaking up societies and social relations and expanding the selling and usage of opium on a large scale.

The Indian Marxist scholar Utsa Patniak estimated that the consequence of British imperialism in India over time drained around $45 trillion from the economy.

The original Stratford Place was built with good quality houses on either side. Those on the eastern side at 2 – 7 are still extant.

Number 3 is the High Commission of the United Republic of Tanzania. A former German colony it was taken over by the British Empire after the First World War. It was then managed as an extractive colony producing sisal as a primary crop, with secondary crops of cotton, coffee, tea and tobacco. It was an unequal and exploitative relationship between a global military power and a much weaker nation-state.

Number 5 Stratford Place has a number of brass and metal name plates, the sort that can be found all over central London. It’s often worth checking up as to what they are. These are signs and indicators of the many nodes of global capital offering a range of financial and other services.

You will notice ‘Lonmile’ which also has an office in Dubai. Their website promises to design A Fortress Forged in Trust for your investments, and help in setting up a family office. The website reveals a lot more than it says and the words and graphics work to suggest connections with the European merchant families of the past. This is how some of the current ruling class imagine who they are.

A more faded plaque at the same address is for Oracle Capital Group. The website is also faded but does include a section on how rich people can use their money to buy a visa to enter Britain.

One of its recent employees was Elena Chirkinyan who left the company in the summer of 2024. By the December of the same year she was sanctioned as a ‘key member of an international money laundering network’. The Daily Mirror covers the story.

Retrace your steps back to Oxford Street. On the corner of Stratford Place and Oxford Street note the brown brick building with pilasters on your right hand side. It is currently (as of December 2025) a Superdry shop.

212 Oxford Street

Superdry began in 1985 as a market stall in Cheltenham, run by Julian Dunkerton and Ian Hibbs. Since then it’s developed into a global company with outlets in 157 countries. For a while Superdry did very well. And then it got into all sorts of financial problems and was recently bailed out with £400 million of funds by Julian Dunkerton himself, one of the original owners. Capital investment is speculative, like gambling; there is no guarantee of a return. The immense ongoing destruction of capital is also part of the history of capital.

The building itself was constructed in 1921 for the shoe retailer Lilley and Skinner. In the 1930s it claimed to be the largest shoe shop in the world.

Thomas Skinner, one of the original founders, had started making shoes in a factory in Northampton in 1851. This was part of the industrial transformation, from the artisanal, hand working craft of individuals to machine powered manufacturing. Marx describes this process in great detail in Volume 1 of Capital.

By 1951, the company had £2m of share capital, 84 branches and employed 2,300 people. It continued to expand (the expansion of capital) and by 1958 there were 470 retail outlets including 60 department store concessions. The shoes were made in five factories in Kilmarnock and Leicester. In 1962 the company was bought by its main rival, the British Shoe Corporation (part of the Sears Group), for £27.3 m.

From the 1980s onwards the development of mass production of shoes in China began, and then expanded to Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and Eastern Europe. The British shoe industry collapsed, or rather was destroyed, as shoe capital in lower wage economies expanded.

I would suggest you cross to the other side of Oxford Street as you will get a better view of the buildings. You should be walking towards Marble Arch (that is, in a westerly direction).

360 – 366 Oxford Street

This was once Maison Lyons, a Lyons coffee house, opened in 1916. When built it had three restaurants on different floors, one with an American jazz band. These bands played raucous music.

In the buildings original format there was a chocolate factory in the upper storey and a large shop front to the street. This was damaged during the Second World War and the replacement of 1951 was of poor design. It is currently being renovated so let’s see what happens next.

368 Oxford Street

This is a rare example of a well preserved art deco facade which was added to an existing building in 1937.

From 1938 to around 1946 the shop was occupied by Peter Bradley, a costumier.

Stay on this side of the road and walk up to the centre of Selfridges.

Selfridges, 400 Oxford Street

Founded by Harry Gordon Selfridge, a retailer from Chicago, this was one of the first purpose built West End department stores. It was constructed in four phases from 1906 to 1928. The original building was opened in 1909. This is a good architectural and social history of Selfridges by Historic England

The facade is a pleasing mass of American commercialism which manages to avoid feeling dated. It has that quality that all art, architecture and people crave; timelessness.

Above the main entrance is the statue of the Queen of Time, created in 1931 to mark the stores twenty-first anniversary. Take note of the figures on either side of the main doors.

Selfridges has 20 plate glass windows onto Oxford Street. Twelve of which were once the largest plate glass windows in the world.

These plate glass windows were designed to encourage window shopping. One of Mr Selfridge’s many innovations was to keep the lights on throughout the night. Another was to put the goods on display inside the store.

Previously the commodities had been locked in cupboards or hidden in drawers and had to be requested. Now perfume, make-up, beauty products and accessories were piled up in bright colours and enticing arrangements where they could be handled, caressed, held up to feel their quality. This retail revolution can still be seen today throughout shops and department stores around the world.

The opening of Selfridges coincided with the growing international movement for women’s emancipation and in some ways contributed to that movement. There was much focus on the vote; but there were other demands too relating to women’s rights, divorce, custody of children, control of money and assets, legal status, the liberation from corsets and certain types of clothing, ways to ride a horse, cycling, playing tennis, a change to attitudes and behaviours.

The development of department stores, the expansion of office work and the appropriation of electrical technologies by a range of business increased the job opportunities for women. As shop assistants and retail managers, typists, telephone operators and after great struggles, doctors, lawyers and the whole range of the professions.

Women were now encouraged to shop unattended, on their own, without male chaperones. Tea rooms were created and that greatest innovation of all; the toilet, made available at last so any trip to town wasn’t limited by the capacity of the bladder. Any sane society would have started with toilet provision in the first place; which just shows how messed up the nineteenth century could be.

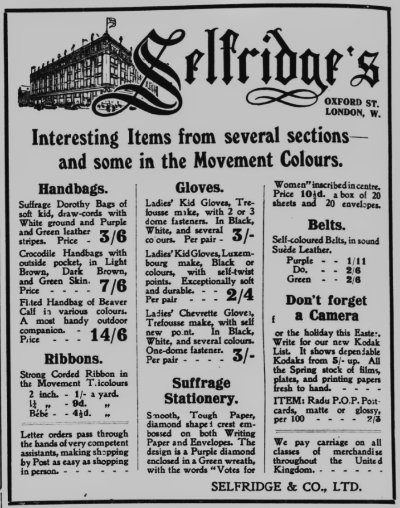

It has been suggested that Selfridges flew the flag of the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) from the roof. There were certainly regular displays of purple, white and green (‘the colours’) in the windows and goods specifically aimed at Suffragettes and their supporters.

Large adverts were placed in the Votes for Women newspaper. In 1913, presumably with Mr Selfridge’s approval, it produced a useful book, The Suffrage Annual and Women’s Who’s Who.

The Marylebone District of the WSPU actively targetted propaganda at shop workers in the West End, including the Selfridges store, to recruit them to the cause.

One of those recruits, Gladys Evans, had started working in the store before it even opened. In 1912 she was arrested in Dublin for setting fire to a theatre where Asquith was due to speak. Although no one was hurt she was sentenced to five years penal servitude.

In prison she went on hunger strike and was force fed 58 times. Over 250 workers at Selfridges, including the staff manager Mr Best, signed a petition demanding her release. This only happened when she became seriously ill and the authorities feared that her death would be attributed to them. She eventually emigrated to the United States where she died in 1967 in Los Angeles at the age of 90.

In 2021 the Selfridges Group was acquired by a partnership between Central Group (a family-owned retail and property company based in Thailand) and Signa Holding (based in Austria, dodgy and full of debt). The deal was worth around £4 bn. Signa don’t appear to have lasted long and in 2025 the Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund acquired a 40 percent stake.

If you have the time, explore some more.

Now head towards James Street (you can work that out from inside Selfridges) and turn right into Barrett Street.

Barrett Street

Lamb and Flag Pub

I have a reference that the Lamb and Flag was once popular with anarchists. But who these anarchists were and what they might be doing in the West End is proving elusive to determine. I would like to imagine Peter Kropotkin sitting in a corner with a pint of ale reading Russian newspapers but this could be well off the mark.

Underground Convenience

This was originally the site of a urinal that was unpopular with the pub landlord and local business. But given the lack of public toilets generally in London I can’t help thinking it was popular with a lot of other people.

3 – 5 Barrett Street

The site was developed in 1904 by Charles Pedlar an engineer and gas fitter based in nearby Bird Street. Once opened a large part of the building was used by the Women’s Dining Rooms Limited. These were restaurants aimed exclusively at the increasing number of women who were working in retail, offices and services.

One of the co-founders of the Women’s Dining Rooms Limited, May Tennant (1869 – 1946), was the first woman factory inspector in Britain. An active trade unionist, she supported the London Dock Strike in 1889.

Now turn left into St Christopher’s Place.

St Christopher’s Place

This was once a slum area and the narrowness of the street suggests something lacking in light, space and air. Substantial changes were made from the mid 19th century onwards but something of the atmosphere of former times remains.

Formerly known as Barrett’s Court it was here that the social reformer Octavia Hill began her work on housing reform in 1869. With financial backing from John Ruskin and Julia, Countess of Ducie, she started to buy houses (including in Barratt’s Court) and used them to develop theories and practice of housing management.

Her plans included building renovation, rent controls and training women rent collectors to both collect rents and act as welfare and social workers to the tenants.

The first buildings were condemned as unfit for human habitation and replaced in the 1870s. These are still extant at North St Christopher’s Buildings and South St Christopher’s Buildings (1882 – look for the plaque). They still look good; I wouldn’t mind a flat here myself. The ground floors are retail, deliberate additions to help provide a source of income to help subsidies the housing and social work.

In the 1960s the area was at risk of a more disturbing redevelopment; concrete block-ism. This would have destroyed a slice of time and changed the whole character from something now unique to another lump of urban blandness.

Thankfully the developer Robin Spiro was seduced by the charm of the area and picked up a plea for help from the existing bricks, tiles, lintels, doorways and window panes. In the 1960s it became a trendy shopping street part of a new wave of consumerism, electronic pop music and an atmosphere of rebellious optimism. It still has a quirky air and it’s the sort of place people discover for themselves. And things we discover, we often like more than things we’re told that, ‘we must see’.

Continue along St Christopher’s Place until you get to Wigmore Street. Turn right and then left into Marylebone Lane. You could take a short cut along Jensen Court. This is what I usually do but then I have walked here a great deal. Both are good in different ways. Let’s assume you decide to use the Marylebone Lane route.

Marylebone Lane

The charm continues and there is much to like here with the collection of individualistic shop fronts and a sense that this really is part of London, still hanging on to character against the sprawl of glass and concrete blocks.

This is twisty and curvy and, psychologically we all like curves; we are not, as Corbusier suggested, geometric animals.

The building which is now Vitsoe is a curious addition and appears as a slab and block modernity. In December 2025 there was a reference on the plate glass to Deiter Rams one of the great designers of hi-fi systems and a product of the Frankfurt electronics and radio industries.

Hinde Mews just seems to be some sort of oversight in terms of spatial use; but according to the UCL survey of London (see link above) it once ‘provided a buffer between the best part of the estate and the poor district to the south, very much an Irish colony by the mid nineteenth century’.

Bentinck Mews

This is worth a diversion into. It will help form an idea of the industrial production that once thrived in this area. In fact all the little nooks and crannies and side streets are worth exploring. You can enhance the walk by your own further research.

Bulstrode Street

If you turn right into Bulstrode Street you will see a red brick apartment block at numbers 8-10. Look out for the scallop shell doorway. This was built in 1906 for the organisation, ‘Housing for Working Girls’. This had originally been established in 1878 as a charity, ‘Homes for Working Girls in London’.

Towards the end of the 19th century several organisations of this sort were established. They reflected the increasing number of young single women seeking employment (and perhaps adventure and freedom) in the new industrial and service industries.

These organisations provided board and lodgings in buildings that were often well designed (Bulstrode Street has carvings by H.C.Fehr). As well as individual bedrooms, common rooms and opportunities for socialising were available. Some of the organisations exerted religious and moral pressure; but not all. And simply being able to walk around the streets of the West End unsupervised must have had a liberating impact on these young women.

There was also specific provision for ‘foreign’ young women in the city. The 1891 census recorded residents in such hostels from Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Bohemia, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland and Jamaica.

There is a good overall history by Bonniee Emmett here: Housing for Single Working Women in Inter-War London, 1919 – 1939. A PDF can be opened from the webpage.

A pamphlet published in 1883 by ‘Homes for Working Girls’ estimated that 800,000 women across Britain supported themselves through paid work and around 320,000 of those women were based in London.

The western end of Bulstrode Street has some good examples of eighteenth century housing.

Bulstrode Place

Until relatively recently Westminster was a large manufacturing district. There were many small factories and workshops producing commodities for department stores, specialist retailers, and medical practitioners, and components for larger-scale industrial production.

Number 10 -11 was the workshop of Salvoc Ltd, makers of optical safety lens for the use in goggles. In 1944 it advertised for ‘young women to work 40 – 50 hours per week on war industry work’.

It is now the site of Alliance Medical which offers radiology services including PET-CT, MRI, Cardiac MRI, Ultrasound, X-Ray imagining, fluoroscopy and diagnostic services. Alliance Medical is a multi-billion private company based in Warwick, England.

Between 1965 – 1975 one of the buildings in Bulstrode Place was used by the Sidney Webb Children’s Theatre Workshop (I have not been able to determine which building it was). This was an innovative theatre for children where they acted, built the props, made the costumes and managed the stage lighting and scenery.

Cross Keys Close

This is a great find for those who like exploring, a remnant of another London; less corporate, less homogenised, less dominated by commercial real estate capital.

The address of 1st Floor, Cross Keys Close, Marylebone, London W1U 2DW has 51 companies registered at Companies House. Sound suspicious? Part of its business involvement is student housing, which is generally a fraud in its own right.

In a curious tear in the space-time continuum, in 1955 the same address was involved in a mail order fraud of £20,000.

In the 1930s, Scholl and Sons, manufacturers of medical equipment were based here. Unfortunately I cannot find the exact address.

There was a radio dealer in the close in 1945 and a firm called General Radiological Ltd was based here in the 1950s.

Number 4 Cross Keys Close was built in 1903 – 04 as stabling for John Davies, a dairy man. Boosey and Hawkes then turned the building into a workshop making bandsmen’s uniforms. After the Second World War it was used by Peter Cox, a specialist in stone cleaning and pioneer in the use of chemical damp proofing.

Since 2004 it’s been the base of BBS Capital which arranges loans for real estate companies. To date the company has raised over £15bn for the development of offices, residential blocks, hotels, warehouses and shopping centres.

A fascinating progression. But how is such change explained?

There are more plaques on one of the buildings. Cairngorm Capital with 12 employees and committed equity capital of approximately £400 m. Blandford Capital, which employs seven people. It is a private investment office so it does not need to disclose the assets under its management.

Go back to Marylebone Lane and turn right into Marylebone High Street and then very shortly turn left into Blandford Street. If you have time, a stroll along Marylebone High Street is pleasant. There are several places for refreshments and this might be the place for a timely break.

Catholic Church of St James, Blandford Street

The main entrance for the church is on George Street but the Blandford Street entrance is usually open. It is a quiet space to have a rest for a few minutes.

The church is in the neo-gothic style by Edward Goldie. It was completed in 1890.

The history of Catholicism in the 19th century is out of the scope of this walk, but park that idea somewhere for a future walk.

64 Blandford Street

An earlier version of 64 Blandford Street is the building we really want here. Unfortunately it no longer exist so we must conjure up our realistic imagination.

If you stand at the current 64 and look at the buildings on the opposite side of the road, you will see the type of buildings that we’re thinking of. Nineteenth century London standard terrace with bricks and geometric windows. Keep this image in your head for 64 would have been the same. And this was the headquarters of the Marylebone district of the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union).

The WSPU was founded by the Pankhursts – Emmeline, Richard, Christabel and Sylvia – at their home in Manchester on 10 October 1903. In some ways it has become synonymous with ‘Suffragettes’ but there were other organisations too. The WSPU was the largest of the groups and due to its adoption of militant tactics is the best known.

Votes for Women was the main newspaper of the WSPU and it is fascinating to read through its archive. It is accessible online at the British Library Newspaper Archive.

The newspaper archive suggests that the Marylebone District was a well organised and effective branch. All the characteristics and activities of the Suffrage movement are recorded. Chalking on pavements, weekly paper sales (there were regular reports of more than 500 sales a week), lessons in how to organise and how to speak at street meetings (held in Harley Street), banner making, visiting the local shops to ask if they would sell Votes for Women. By one estimate more than 10 percent did.

Not recorded, but no doubt taught, ‘how to smash a plate glass window’ and ‘how to make incendiary bombs for post boxes’. There is a detailed reference on how to do the latter in Margaret Haig, 2nd Viscountess Rhondda autobiography, This Was My Life. The book also contains a detail account on page 162 of window smashing in Oxford Street by Haig’s aunt:

“Aunt Jenatta, carrying a small and unobtrusive parcel, which was in fact a hammer done up in brown paper, strolled down Oxford Street…..with soft curly hair and a very gentle and spiritual face – the face of a saint – and she dressed well.

It would have needed a wily policeman to identify her with the popular view of the Shrieking Sisterhood. Opposite the windows of D.H. Evans she stopped, and murmuring to herself “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with all they might” upped with the hammer and splintered the window.

She told one of her daughters afterwards that it had been almost impossible to strike that blow. The great plate-glass window looked so beautiful and well made that she could not bear to destroy it. However she did it all the same, and then moved on to the next and the next. Each time she struck she murmured the same text”.

Detailed records were kept on mapping out the deliver of leaflets and circulars to individual households. Reports were produced and printed in Votes for Women which described street meetings in details, preparations for demonstrations and the time and place of ‘at homes’.

One of the organisers in Marylebone was Elspeth McClelland (1879 – 1920), originally from Keighley in Yorkshire. She started training as an architect at the Polytechnical Architectural School in London in 1899, the only woman among 600 men. She practised as an architect from 1904 onwards.

The Suffragette newspapers of the early part of 1910 capture the mood of excitement, optimism and enthusiasm which defined the women’s movement and lead up to the mass demonstration of Saturday 18th June. Trains from Manchester, leaving the city at midnight, arrive at Marylebone station early in the morning. Suffragettes from Liverpool, also arriving at Marylebone were informed that ‘the saloon car will be decorated with the colours’.

[Marylebone Station should be a point of call for those who wish to map the topography of women’s emancipation in London. It was here that the trains from Aylesbury arrived carrying women who had just been released from prison there – see foot note below]

For the demonstration on the 18th of June each district of the Suffragettes was allocated a specific space. It was due to march at 5.30pm but vast crowds gathered throughout the day. Messenger boys were paid to help organise the contingents.

There were at least three Suffragettes on horses to help arrange the crowds; Flora Drummond, ‘the General’, the Hon. Mrs Haverfield and Miss Vera Holme, both wearing ‘long dark riding coats’. (There is a superb account of the whole day in Votes for Women from 24th June 1910).

At the very front of the demonstration stood Charlotte Marsh carrying a banner. She was one of the first three women to be force fed, along with Mary Leigh and Patricia Woodlock. Marsh experienced this violent, painful and humiliating abuse on 139 occasions. Her release from prison was delayed by an act of vindictive malice by which she missed the death of her father. Not only was she a Suffragette militant and activist, she worked as a sanitary inspector at the London County Council.

Next came the flag bearers with ‘the brave colours of the Union’, and then the the WSPU drum and fife band. ‘Then comes the first part of the Pageant of Prisoners, representing the 617 imprisonments that have been suffered for the cause of freedom, carrying a special silk banner’. They were dressed all in white and carried silver wands.

The vast procession included women artists with ‘palettes covered in ribbons’, the Actress Franchise League, women from the London County Council, sanitary inspectors, typists, stenographers, teachers, women graduates in gowns, nurses in uniform,

‘There were also sweated workers in poor clothes and hats that knew no fashion. They were boot-machiners, box-makers, and shirt-makers, who fight daily with starvation. They too, had beautiful flowers in their hands’

The police estimates of the numbers are absurdly low. Some estimates suggest that the demonstration was at least 250,000 strong.

The mood of great optimism and enthusiasm changed however with the shocking events later in the year. On the 18th November around 300 women tried to enter Parliament. They were met with ferocious violence by the police and the lumpen mob the police encouraged. Women were beaten, dragged across the pavement, sexually assaulted. At least two women subsequently died including one of Sylvia Pankhurst’s aunts. It is alleged that Winston Churchill was responsible for the instruction that sanctioned this disgrace.

Dorothy Agnes Bowker, one of the Marylebone Suffragettes who lived in New Cavendish Street had her head smashed against a lamp post by a police ‘officer’.

Perhaps these these events and others help explain how Gladys Evans, the shop worker from Selfridges, came to be involved.

Continue along Blandford Street and then turn right into Chiltern Street.

Chiltern Street

Should I win the lottery, that desperate tax on hope, this is where I should like to live. This is a true nineteenth century street which oozes a special charm. It is perfect for a leisurely amble.

The fire brigade station was built in 1889 by the London County Council as part of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. There’s even a stone sculptured head of a fireman.

Wendover court was built between 1890 – 1900 by the Artizans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company. This company, also known as the Artizans Company had been established in 1867 by William Austin, an illiterate builder.

He bought together other builders and clerks and together formed a joint stock company. The ambition was to build low cost housing for the respectable and industrious poor on cooperative principles. The original apartments lacked bathrooms – the facilities were shared – but as you can see from the exterior, considerable thought and energy was expended on the style and design.

The ground level shops help create a lively street life.

Turn right into Paddington Street. Note the inappropriate lump of ‘Chiltern Place’.

Chiltern Place

One of the many problems with the liquid character of capital is that it flows where ever it can make money regardless of actual human needs, urban design or common weal. Part of this flow is into luxury apartments.

The building itself is in a new style which is so bland it doesn’t even have a name. It isn’t Gothic, Neoclassical, International Modern or anything else. And yet it is everywhere. Odd shades that aren’t really colours, generic shapes that lack geometric definition, materials that all appear to reduce to the look and feel of plastic panels.

And yet it is a blandness wrapped around a mailed fist. It’s primary purpose is to generate revenue. Any threat to the actual power of capital that is concentrated here will be met with a brutal response.

Now turn right into Paddington Street Gardens

Paddington Street Gardens South

The height of Chiltern Court casts a shadow over this much needed open space. Chiltern Court is new but it replaced an office building of the 1960s. That earlier building must have had planning consent up to a certain height; and that height allowance has been passed on to this new development. It would be interesting to know the full history; or is that history now lost?

Paddington Street Gardens is a good place to sit down and rest. The Ginger Pig at Moxon Street is only a 100 yards so away. It sells tasty sausage rolls and pasties and there are vegetarian options too. These snacks can be eaten in the gardens while you watch the world go by.

Walk across Paddington Street Gardens towards the far corner where the gate leads to Moxon Street. Turn slightly back on yourself and turn right into Ashland Place and then into Ossington Gardens and Grotto Passage.

Ossington Gardens and Grotto Passage

This is a collection of well built four storey buildings, originally known as the Portland Industrial Dwellings. Nine blocks were constructed in total, mostly between 1888- 89. This was built as social housing and supported by a communal steam laundry. They are a good example of a certain style, philanthropy and patronage.

The build quality was good but the accommodation was small and basic and toilets, two to each landing, were shared. Of the £30,000 capital required for the building, around £10,000 was provided by Lady Ossington and Lucy, Lady Howard de Walden.

The intention was to improve the social conditions across the estate. Prospective tenants were vetted for character, temperance and suitability. This was carried out by Octavia Hill who lived nearby in Grabutt Place. Hill acted as the general housing manager.

There is more detail from the UCL Survey of London, West of Marylebone High Street produced by the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Grotto Passage

The Grotto Ragged and Industrial Schools and Refuge for Destitute Boys was established here in 1846 It was claimed that it was the only place in London, apart from the workhouse, which would take in poor and destitute boys without ‘subscription or recommendation of any sort’. An early supporter was the Earl of Shaftesbury.

One reporter who visited in 1867 wrote:

“In honour of my visit firewood chopping was suspended for a while, and hymn singing substituted. Accompanied by a harmonium, those thirty waifs and strays sang – many of them in gruff manly voices, but all sang, – “I was a weary wanderer” & c.

The lady who accompanied me added little comments in French, so as not to be understood by our sharp-witted friends. That boy was a clever poacher; another lost his mother, and was trained as a thief, but fled to the Grotto; a third was an habituéof the gaffs, &c. Many of the former inmates of the Grotto, starting from such antecedents, are now in excellent situations as footmen…”

Some boys were ‘sent to the colonies or into the merchant navy or place in domestic service’.

Make of this what you will. At least one of the former inmates worked their way up to the position of a butler. He returned one evening to explain his story which was recorded in the Surrey Comment of 7 May 1867.

‘Boys, before I came to the Grotto I was the biggest thief of you all’.

Walk to the end of Grotto Passage and then turn right into Garbutt Place.

Garbutt Place

Garbutt Place was the site of Octavia Hill‘s first reform programme. She lived at no. 2 and you will see the Blue Plaque. The area had been known as Paradise Place;

Hill wrote of the slums there:

“The plaster was dropping from the walls, on one staircase a pail was placed to catch the rain that fell through the roof. All the staircases were perfectly dark, the banisters were gone, having been used as firewood by the tenants”.

Sadly, there remains far too much housing in England which continues to have damp and mould and leaking roofs.

Hill was of a certain type of nineteenth century reformer and is not without controversy.

Turn right into Moxon Street. In front of you is Marylebone Square

Marylebone Square

There is a pithy phrase that runs something like, ‘the more appetites a person has, the richer they are’. But it could be added, that too many appetites can make a person queasy.

The first impression is of Dubai and the global bland. When I did some vox pop in the street a couple of people – unprompted – said more or less the same. The marketing department however has a different view, and in the interest of balance I shall quote it here:

“Known for its distinctive red-brick Georgian architecture, Marylebone is a district that has carefully preserved its past – and Marylebone Square is a sensitive addition. A contemporary interpretation of a classic London mansion block, it blends into its historic home with a subtle modernity that enhances its surroundings.

Externally, the building is a rich palette of glazed terracotta, with intricate yet robust cast metal balustrades adding a European sensibility to the design. “It was designed with a singular vision,” says lead architect Simon Bowden, “so it has a cohesive quality – and a distinct character that’s strengthened by the robustness of the natural materials.”

The area is known for its ‘distinctive red-brick Georgian architecture’ and yet this is a petrol-dollar antithesis.

It comes across as being bloated, pushing itself into the streets on all four sides in a way that earlier mansions do not. It feels constipated, the flatulence that will not come.

Such buildings have inflated ego as they must meet the demands of people with inflated ego. The top flat is a penthouse. What else?

According to someone I spoke to in the street there were (or are?) problems in the selling of that penthouse. As a temporary measure it had been used for classes by a local yoga group.

This may be a tall story, but if so, it was well invented on the spur of the moment. Which makes me suspect it’s true.

And so that ends this particular Radical Walk. There is so much more to see and tell of these, and other local streets. This is just a tasting menu if you like. Anyone can create a Radical Walk. All you need is curiosity and imagination and those are best when they are free.

And now these dreams are done, we must learn to dream anew.

Footnote:

‘Don’t you know? It’s for the window breakers!’, said one porter to another at Marylebone Station last Saturday morning’.

‘The platform was gay with Suffragettes, carrying bunches of flowers. At the entrance to the station stood two paper sellers; every minute, more people, wearing the colours, carrying more flowers arrived on the scene.

‘…the 10.26 from Aylesbury was going to bring home six women who had served the excessive sentence of four months imprisonment for making a Suffragist protest’.

As the train arrived, two lines of women formed. First members of the public got off the train, then the six Suffragettes who were showered with flowers in the colours of purple, white and green.

‘a great burst of cheering went up, as they walked down the lines, greeted as they came, covered with flowers, receiving a welcome such as any victorious General would be proud to receive on his return home from the war’.

Votes for Women, 21 June, 1912

If you are interested in finding out more about Radical Walks please use the contact link at the top of this page.

You must be logged in to post a comment.