The voice of a London girl floated up the stairwell of the bus.

‘Thank you’, she said to the driver as she alighted.

It was the 319 bus and now it crossed Battersea Bridge. Far away, downstream, the North Sea had pulled the water from the river and houseboats and the occasional steel clad ligther rested languidly on the sand and gavel of the river bed. In the west, the grim no-topia of the Chelsea water front. Sterile, symmetrical, cynical and clinical. I always imagine such places full of depressed people who fret because their large piles of money are never quite large enough. But this is just imagination. There are plenty who laugh and mock and scorn the poor.

‘Cheyne Walk’, announced an electronic voice. There was something mildy suggestive about the intonation, delivered with a raised eyebrow and intriguing expression. As if ‘Cheyne Walk’ was an invitation to an unexpected erotic adventure. Afternoons spent within the luxury of the senses followed by good food and a late evening walk along the river. These could possibilities; but capitalism has no imagination. All is reduced to the grubby cash-and-carry, chip-and-pin, financial domination and relationship.

Out of the window of the bus no opportunities for convivial pleasure can be seen. Just the industrialisation of motorism, the glum expressions of those stuck in traffic, the inanity of Deliveroo and Uber Eats. Giant capital sucking up cheap global labour, a circulation of junk food, a feeding frenzy of oils, fats, sugar and chemical additives with the cheapest cuts of meat, chlorinated chicken and artifical flavourings.

‘Cheyne Walk’ momentarily conjured something else. But capitalism won’t let us have it. Capital refuses that we might live in the realm of the senses, with the automation of production and the autonomy of the self.

The bus continued along the Kings Road, rolling along, creating a friction with its wheels on the hard tarmac road. Fourier claimed to have found the important knowledge of the four movements which were missing in all the existing 400,000 volumes on philosophy and the world. Perhaps there are 400,000 books on London, but how many really tell it’s tale? And is there something missing in our theory? Is there an idea waiting to be discovered that will make us see the city in a different way, that makes us realise that all along, the true character of social reality had yet to be revealed?

I changed buses at Sloane Square outside the Peter Jones department store. I like the building and it’s worth a look inside. From the fifth floor windows in the furniture department there are views across north west London. There are few if any tower blocks in that view. Instead there are domes and cupolas, the red brick apartment blocks with terracotta roof tiles.

It’s a different London. It’s how London was at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and how the city might have developed had the First World War not broken up a certain time-space continuum. The war was a great disruptor, a man murdering machine. Bodies were broken, spirits were crushed; the thoughtful intelligence of Arts and Crafts and Garden Cities was replaced by a harsher world of re-inforced concrete, discordant sounds and harsh words. How could it be otherwise when millions laid dead upon the battlefields, worms moving slowly through mouths and eye sockets where the bodies lay in smashed up corpses in the trenches and the shell holes.

I walked up to the Dorchester hotel and chatted to a man outside in a top hat and green frock coat. He was helpful and interesting about the history of the building. I was conscious of not making him feel uncomfortable by asking him questions that would impossible for him to answer while he was at work. I asked him if it was ok to go in and have a look inside which he said it was.

There is someone who stands outside the hotel in a dark suit and it’s their job to open the door for people coming in and out. He pointed to some floors and said, ‘no further than those flowers, the guests are still having breakfast’. I asked the receptionist if I could take a couple of photographs, ‘that’s fine’, she said, ‘but not of any of the guests’. I explained I write about architecture (really?). She didn’t say anything. I wonder what sort of other nonsense they have to listen to?

While I was talking to her there was a moody looking man having a moody sort of discussion with one of the other receptionists. Then another member of the hotel staff arrived. A huge wedge of £20 notes appeared and was put in a drawer. The moody man didn’t look any happier. I had a feeling of being up close to the super rich. I wonder what they see, and how they see the world, for personally I felt invisible.

I walked along Curzon Street, frequently stopping to consult the volume of Pevsner, ‘London 6: Westminster’. This was a slow but rewarding exercise. I discovered torch extinguishers on the south side of the street, wrought iron work, balconies and so much more.

Pevsner is of course exemplary for the architectural detail and history. What I would really like is more of the social history and more history of the changes of the architectural design; and some of the whys and wherefores. Why was wrought iron popular at a certain time? Why was the building style of the 18th century as it was. The Enlightenment? A technical deterministic reason? Something else? What about brick production, glass production, what sort of machines and tools; all that sort of stuff.

Perhaps it was being so engrossed in the book; lots of people smiled at me as they walked past at various points.

Outside one of the 18th century houses I stood and examined the door bells. More hedge fund management companies. And then I stood back to take a photograph. A car drew up and a loutish looking boorish looking ex-public school boy type got out. Not in a smart suit with manicure and blow-dry hair. No, this one was uncouth. He looked a shouting sort. The rebellious outsider making lots of money. Perhaps they weren’t a hedge fund manager at all. What do they look like? I need to spend more time just standing in the street.

Later, when I was standing outside the Connaught Hotel, a huge Range Rover or something, came to a stop outside the main entrance. A man in his late twenties or early thirties got out and passed the keys to a doorman without really looking at him. I watched him go into the hotel itself. His jeans were half way down his backside like some sort of gangsta type from a tough American city. He wore a multi-coloured woollen hat. He walked in with a pimp roll. There they are, our class enemy and they will stop at nothing if they think their interests and their life style is being threatened. It was illuminating and depressing in equal measure.

After a while, I got tired and fed up with all this wealth. It’s not because I don’t have it; all I would like is just enough to be able to move back up to London. It’s not that, it’s just that the people who have so much wealth don’t give the impression that they would be the sort of people you would want to spend any time with. This was all preparation.

I thoroughly enjoyed the Radical Mayfair Walk: Moneybags Must be so Lucky. It poured with rain. A lot of people cancelled and I can understand why. I always want to say to people, ‘listen, it doesn’t matter! I hope you’re ok and please don’t fret!’

I stood in a doorway near the Dorchester hotel. I thought the person on the other side of the road might be a potential attendee. I was wet and cold. I’d tried to buy a waterproof jacket earlier but couldn’t find what I wanted. Instead I’d found a thick, padded jacked that should have been hundreds of pounds. I bought it for sixty quid. Less than two return trips to London, just consider that. But it was heavy and hot to wear. I left it in Peter Jones. Now I was standing in the rain I was regretting that decision.

Anyway, the guy on the other side of the road was coming to the walk. I liked him and his manner and his interesting conversation. Slowly more people turned up. Some from leaflets they’d found in the Mayday Rooms and Housmans and Skoob and so on. Off we went. I was conscious of my notebook becoming ever more sodden. I was aware that I was getting more and more wet, I could see the people in front of me holding umbrellas and crouching down inside their anoraks and raincoats.

I passed sprigs of rosemary around. A symbol of the Levellers. I like the idea that there was a Leveller presence in Mayfair on this day in July 2023. I like the idea of Radicalism. I like the idea of Revolution. These ideas make me feel alive. And surely the point of being alive, is to at least occasionally feel alive.

Curzon Street, Crewe House, Shepherd Market, 5 Hertford Street, back to Curzon Street, a couple of stragglers caught up, Queen Street, Charles Street; Berkeley Square. A slave trader once lived at number 50. At number 14 lived Lewis Harcourt, Colonial Secretary. Dr Ethel Smyth smashed his windows with two other suffragettes in 1910. They had had enough. They asked politely for votes for women and they were met with ignorant narcissistic indifference. When 300 women went to Parliament Square on the 18th November 1910 they were beaten, sexually assualted and abused by the police and the riff raff the police encouraged.

It is generally accepted that two women lost their lives as a result of these disgraceful events. Here in the rain in Berkeley Square these events came to live again. And the militant tactics which the women then adopted. The rain came down. The stupid rich people drove past in their bang bang exhaust type cars. But if the spirit of the Suffragettes from a hundred years ago can be bought to life again, and if we can learn and act upon it, then ….well then, anything is possible.

Someone was walking next to me as we walked up to Hill Street and then Farm Street. As we passed the crass banality of Annabel’s at no 46 Berkeley Square we were debating militant tactics, when to make publicity, how and when and why to involve wider forces. There were three Rolls Royces parked in a row. And on the pavement a discussion walking by throwing out sparks that could start a revolution. That feeling of being alive. Surely that’s what we live for?

We stopped in the church of the Immaculate Conception. Someone was playing the organ. It was good to sit down, out of the rain, looking at the stained glass windows. I liked being here with this group of people, it had a sense of Christopher Alexander and the quality without a name. At least for me. Maybe others.

As we approached the Audley Arms the person minding the door for the restaurant, wearing a straw boater and holding an umbrella stepped forward and said, ‘there’s a good pub here’,

‘That’s just where we’re going’, I said. You have to be friendly. There are 85,000 people working in Mayfair. Most of them I would argue are on our side. People who see the rich up close all day are never going to be their friends.

The pub was lovely. A saturday afternoon in a London pub. Not too busy and without shouting people. The beer was good, a bit expensive. We found a table and conversation started up, relaxed and friendly. Marx had suggested that the conversation, beer drinking and camaraderie of the exiled German workers in Soho in the 1850s was a ‘thing in itself’. It was a creative act. When I explained this to my lovely friend J – W – he considered and said, ‘so conviviality as an antitode to alienation’. This is brilliant. That we have the power to to destroy alienation through our interactions with each other; being comrades, conviviality, friendships, kindness.

I might say again, it’s Christopher Alexander thesis of the quality without a name.

I really enjoyed the conversations. I really enjoyed seeing people that I feel towards each other we express friendship.

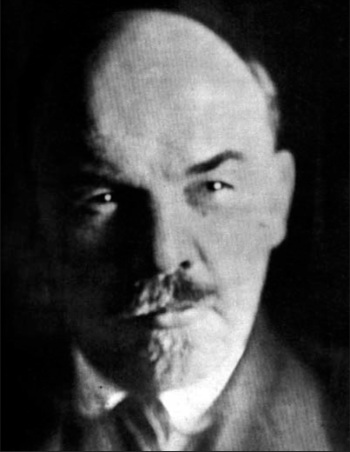

There were some people there I’d not met before and I enjoyed their company immensely. I learned so much. As if there is a new movement all around us, uncertain, at times an uncertain smile. Ragged around the edges, deep core ideas and commitment. I felt old, but overwhelmingly I felt so young. Marx, Lenin, misconceptions, party politics, political organisation, organisational culture, political culture. The need to be philosophical. Everything was there. It was interesting to listen. Always much more so than talking. And then a misconception about Lenin. It wasn’t a big thing.

‘But Lenin wrote that in 1910’, I said, ‘just imagine that Lenin was here now. And you’re trying to hold him to something he said one hundred and thirteen years ago. He’d quite rightly say that’s ridiculous’.

There is stuff to criticise about Lenin, but there’s a great deal to learn from too.

Maybe I shouldn’t drink so much beer in the afternoon but for a moment I thought I caught Lenin in the corner of that table smiling with his eyes and laughing and sipping on a half of beer.

Because if anyone wants to argue with Lenin it’s a modern, alive Lenin they must confront. Not a fossil. That was never Lenin.

In Farm Street we stopped briefly to consider a new building being constructed. I’d been there yesterday talking to the builders. They were working to attached large wooden units to straps so they could be hoisted up in the air by a large crane.

‘Are those floor units?’ I asked.

The two men in orange jackets and trousers and hard hats and big boots stopped and looked at me. They both had Yorkshire accents and explained that they were pre-fabricated floor units that came from Sweden. We talked. They were alive too. Is it only in brief snatches of conversation where we come alive? Do they feel alive in that labour? I doubt it. But they were skilled confident workers.

On the walk I referenced those construction workers.

‘We need the automation of production, and the self-autonomy of the soul’.

At least one person in the group of people nodded. That’s enough. It’s a flash of life. Sparkling like a diamond, but more powerful, as it is human, with agency.

These connections need to be made. Lenin – Marx – construction workers – transport workers – admin workers. We must find a language and practice to enable this.

The fragmentation can only be overcome with a universal opposition. Tough, but possible, potentially, revolutionary.

You must be logged in to post a comment.