Update: Thursday 31 July 2025

I am organising a ‘Red Vienna Radical Walk’ on Sunday 28 September 2025.

Meet outside the Rabenhof Theatre, Rabengasse 3, 1030 Wien at 14.00

More details here:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/1548015378669?aff=oddtdtcreator

If you want more details use the contact form, link on the top right corner of this page.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There are so many different ways to explore Red Vienna it can be difficult to know where to start. An obvious place might be Karl Marx Hof. It’s well known, big ticket and to this day it’s a symbol of the Red Vienna period. Including its partial destruction, when artillery fired on the building (and many other buildings) in the Austrian civil war of February 1934

It was that event that stuck in my mind on the first reading of GER Gedye’s book Fallen Bastions many years ago. But in some ways Karl Marx Hof feels like the conclusion of the Red Vienna project. I wanted to go further back in time to get a sense of the achievement during the earlier years.

So one Sunday afternoon in September, a nice time for a lazy walk, I decided to go and visit a building that Josef Frank had designed. The walk wasn’t planned, and along the way, I discovered a great deal.

But before we put one foot in front of another, an excellent way to proceed, let’s briefly consider the political context of Vienna in the 1920s.

In the 36 months from the beginning of 1917 through to the end of 1919, parts of the European political system were blown to pieces. Revolutions in Russia, Germany, Austria and Hungary, the emergence of new liberal democratic states in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Jugoslavia, the destruction of the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires.

Workers’ and Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Councils in a huge arc across the continent. Mutinies of troops, peasant uprisings, factory occupations, food riots, worker’s control of parts of production. Nobody was expecting this vast political movement of so many people, ideas and actions. This was the context within which Red Vienna was born.

Red Vienna describes the period from 1919 – 1934 when a majority socialist council was in control of the city. It set out to resolve problems of overcrowding, homelessness, poor quality and expensive housing, lack of amenities and high levels of disease, poverty and unemployment.

In that short period, the council implemented a building programme that created 64,000 homes in around 400 buildings; most of them five storey apartment blocks but including terraced housing and garden city developments.

The housing was supported with kindergartens, schools, studios, cinemas, theatres, mother and baby clinics, gardens, parks, allotments, welfare services, sand pits, swimming pools and more. Sigmund Freud provided a weekly psychiatrict clinic. Adolf Loos and Josef Frank and others provided artistic, technical and design skills and advice. Poverty, infant mortality and infectious diseases rapidly declined.

The legacy of this remarkable achievement can be discovered across the city. And those 64,000 homes continue to provide a core of the public and municipal housing to the inhabitants of the city. Housing that is still low-cost and good quality. And most of it is around 100 years old.

Ottakring Brewery

The Ottakring brewery is a good starting point for this walk. Nearby is the Joseph Manner factory that makes chocolate biscuits and wafers (there is lovely smell of melting chocolate in the air).

It provides an industrial working class edge that is sometimes now missing from cities. Factory production, docks, railway marshalling yards, warehouses, workshops help to keep cities grounded. All those things still exist (on a large scale than ever) but they are often out of sight as it were and no longer in the centre of major European cities.

Dr Friedrich Becke Hof – Thalhaimergasse 36

The riff of the angled bay windows provide a jazz line along the main street front. This is a relatively common motif in large blocks and it locates us in the 1920s. Louis Armstrong, Speakeasys, cinema, telephones and airplanes. The interior of the estate takes a more unusual turn. The green statues are of a different sensibility, more Peter Pan than Al Capone. They were designed and produced by the sculptor Robert Obsieger.

I often wonder what small children would have thought of these? As symbols of home, slightly weird and calling from a bigger world that is both strange and curious. Walk across, or around the interior courtyard, for an aspect that changes the tone once again. This is a medieval cloister with artisanal brick work and forms part of the estate. It’s modern in build, but ancient in atmosphere. A fascinating addition to any large housing estate. It creates a presence of a different age.

The estate was named afer Dr Friedrich Becke, a natural scientist and mineralogist.

Schmelz Housing Estate – Wickhoff Gasse

The estate was planned before the war but delayed until revolutions had bought the war to an end. It was one of the first housing estates to be built by the new socialist council. The architect and planner was Hugo Mayer and it was designed along garden city principles. The large gardens and allotments are still in use today and provide a strong rural sensibility in an area which is actually part of the inner city.

A second phase was built between 1921 – 1924 between Wickhoff Gasse and Gablenzgasse and included some three storey houses.

It is worth exploring the whole estate. Walk through it, around it, and sit in the square for a while near the pub. Or go and have a drink if it’s open.

Hufeisenbau – Wickhoff Gasse

On the other side of Wickhoff Gasse is the Hufeisenbau built in 1924. It has a modernist Italianate feel to it and is probably the most run down of any of the municipal housing buildings I’ve seen in Vienna. Across the city there is an active programme of renovation so perhaps this is just in a queue to be fixed.

It does show however the importance of regular maintenance of estates, and what happens if that isn’t done.

In England some housing estates appear to have been deliberately run down so that they can then be knocked down and in the process council housing, which could have been redeemed, is replaced by private housing and housing associations. More expensive and less rights.

A walk along Wickhoff Gasse reveals a nice example of historical development. How the earlier ideas of Garden Cities were replaced with larger, estate complexes. Putting aside aesthetics for a moment, one of the pressures that provided this change was the need to house large numbers of people as quickly as possible.

But I also wondered what the impact on the housing was of the easing of the revolutionary pressure?

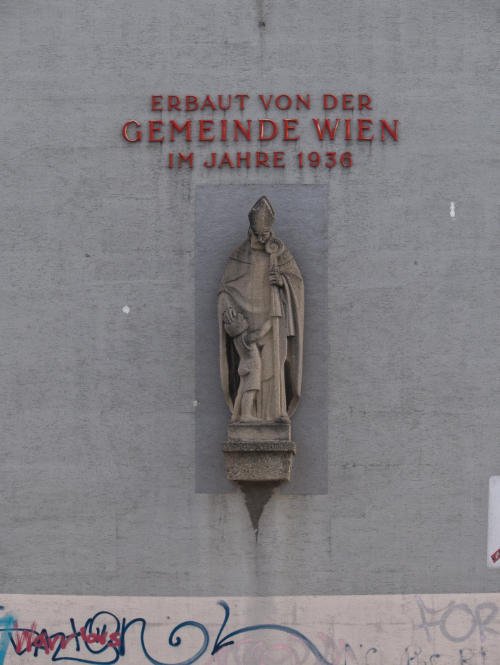

Minciostrasse – 1936

As you come out of the garden city, this is what’s encountered. A building from 1936 when the fascists had gained political and social control of Austria and Vienna. They murdered, tortured and imprisoned their political opponents and banned newspapers, political parties and trade unions. The social housing and the supporting health, education and welfare services were all curtailed. Authoritarianism and prohibitions replaced democracy and free speech.

Throughout the 1920s, the reactionary right had fought a relentless cultural war against Red Vienna. They used lies, anti-semitism, violence, smear campaigns and slander, backed with large amounts of money from Mussolini. Now they were in power, what would they build? Not much, and the housing was of poorer quality and of cheap design.

This is a rather stumpy building which close up has a dour atmosphere and an abandoned cardboard box feel about it.

Draskovichgasse

Continue along Draskovichgasse and note some of the typical architecture of Vienna pre the First World War. There are examples of sturdy little Biedermeier cottages and later apartment blocks with facades covered with all sort of ornamentation. It’s this sort of ornamentation that Adolf Loos decried in Ornament and Crime.

He wasn’t against decoration on building per se. But he did object (in his usual amusing and acerbic style) to the profusion of heads with alarming expressions, large Herculean figures wrestling with porticos and women with tantalising bosoms trying to lure pedestrians up towards the attic storeys.

It’s this sort of street that the architects of the 1920s were working with. Striving to provide buildings which represented both continuity with the past and yet the creation a new world. It is to their credit that they did this with style and panache. No click bait architecture was produced, nothing cranky or contrarian or controversial.

The only people who worked themselves up into a lather were the far right, and as we’ve seen above, their idea of buildings turned out to be lacking in style, quality and class. The evidence suggests that the people who moved into the new buildings liked them for their design as much as for their amenities.

I think one of the ways in which the new architecture works is that it looked back in a rather nice way to the Biedermeier period. It referenced those earlier values of comfort, homeliness and domesticity. Personally I think criticisms that these are ‘bourgeois’ values are ridiculous. It’s like saying we won’t listen to Mozart because he was such a good little Salzburg burgher’s son.

67 – 69 Meiselstrasse

How good is this? It has the presence of a magical castle set amongst some mysterious mountains that can only be reached by a path through a thick forest full of adventure and excitement. The Brothers Grimm hide in the shadows, the puppet masters of tantalising stories. When one arrives, the most marvellous things will happen.

I spoke to a woman coming out of the block who explained that she was going to vote in the election (Sunday 29 September 2024, the far-right won).

‘My father was a very political person’, she tells me, ‘and he said forty years ago that the right would come back’. And indeed it has. And they will be interested in the privatisation of this housing so that profit can be created instead of homes.

She asks me what I’m up to and I explain I’ve come to look at the Josef Frank building.

‘I can see that from my flat’, she says.

The estate was built on vacant land from 1924 onwards. From the start it included a kindergarten, communal facilities such as a laundry, and shops. The architects were Rudolf Eugen Heger, Anton Drexler, Rudolf Sowa.

73 Meiselstrasse

Built in 1928 to the designs of the architect Theodor Schöll, a student of Peter Behrens. Schöll had the humble origins of being the son of a waiter. Before becoming an architect he completed a bricklayer’s apprenticeship.

This has a good sturdy dynamic and an example of how blocks were successfully used to fill gaps in the street. Just by bringing forward the central section and adding some drama to those middle windows creates a dynamic straight-line modernism. It’s a very clever building.

4 – 6 Sebastian Kelch Gasse

I got called out here by a woman with a huge dog which thankfully was wearing a muzzle. Although it looked to me like pure decoration. It felt that this dog could discard that muzzle whenever it wanted to. It made a gesture to be friendly, in the way that a drug dealer does when they’re trying to sell you something.

The woman asks me what I’m doing in a tone that doesn’t welcome a fool’s response.

‘What’s he got to hide?’ is the vibe coming from the dog.

I explain in German. So what I think I’ve said is that I’m here to study the architecture and politics of Rote Wien. What she may have heard could be a different thing.

She tells me that she’s lived here for 25 years and likes it a lot. ‘It has high ceilings’ she says, stretching her arm as long as it will go into the air.

She seems to know everyone who walks through this entrance way. A man with a box of tools, a woman arguing with a mobile phone.

I explain I’ve come to look at the Josef Frank building opposite. She’s not aware of who Frank is but she knows that the architect of this building is Heinrich Vana. She shows me the plaque with his name, alongside Karl Seitz, and Hugo Breitner.

The dog wants its tea. The glance it makes towards me is a reminder that it once punched Mike Tyson in the face. This vignette makes me forget to photograph the Frank building properly.

1 – 3 Sebastian Kelch Gasse

This is what I originally came to look at before I was side tracked and distracted by so many other things. Frank never started with ‘bourgeois’ values and ‘proletarian’ values. He started with the principles of light and air and space and high quality build and the appropriate use of materials. He never insisted in a dogmatic way how anyone’s home should look, let alone a ‘worker’s home’.

His pluralist, non-dogmatic and eclectic approach would be well applied to a whole layer of left politics. I unobtrusively observed the people on their balconies, day dreaming and watching the day go by, a woman leaning out of a window, smoking a cigarette. I came to the conclusion that this can be described as good housing with working class people living inside it. I will let others write critiques as to whether or not it’s ‘working class housing’.

5 – 7 Sebastian Kelch Gasse

Is this an early prototype for Karl Marx Hof? This area was fields before the First World War and this block which takes up numbers 5 -7 of Sebastian Kelch Gasse filled a gap that had yet to be built upon. It’s not visible in the photograph but there is also well designed wrought iron-work.

One of the policies of the socialist council in the 1920s was to employ artisans to work on the public housing. This was done deliberately both to enhance the design quality and also to provide employment. This included the creation of statues, iron work and ornamentation.

The architect of this block was Karl Holey, an architectural historian who went on to work as the cathedral architect for St Stephen’s.

I find this rather unbalanced and the balconies too loud and shrill. If it was my balcony I would want it to retain a sense of privacy so I could sit there and read a book or watch the street below without attracting the attention of passersby. These balconies shout too much and I would feel that I was on display.

Gründorfgasse

I will need to come back to this one as I cannot find out anything about it. However, it’s worth noting the brick work around the windows. A nice touch.

The production of window frames and other common elements of the housing were standardised. This reduced the overall costs and creates a commonality across the buildings that helps define them as part of Rote Wien.

Neubeckgasse

Another small block built during 1928 – 29. There were originally 18 flats although this has now be reduced to 15. The plans and design were by Alfred Adler. The block is an example of a more functional style that began to develop at the end of the 1920s.

It was only when I came to process this photograph that I realised how much bigger the block looks compared to the earlier building next to it. I wonder if this was deliberate?

Cervantgasse 9

Rudolf (Rolf) Eugen Heger was the architect of this block, built in 1926. It’s another good example of how smaller blocks were fitted into existing street buildings. I rather like the deliberate pointed roof. There was surely no functional need for this. Flat roofs were proscribed in the building standards of Rote Wien, partly because they were deemed to cost more in maintenance.

In Germany, flat roofs were used in many of the buildings of the Neue Frankfurt project (and elsewhere) and became a focus of unpleasant shouting culture wars that were laced with anti-semitism and the demonisation of anything deemed to be ‘other’.

But what’s this? Both the ‘traditional’ buildings on either side have no visible pitched roof. They appear flat. If this was a joke by Heger it is a very good one.

Hickelgasse 12

This is a small block that fits neatly into the existing street.

The architects were the brothers Adolf and Hans Parr. Adolf studied under Peter Behrens and Hans worked in the office of Hubert Gessner, one of the leading architects in Vienna in the 1920s.

This building fits very neatly into the street. The drop of level on the upper floor is a very smart piece of design.

Cervantgasse 18

This corner block was built in 1929 (I can’t find any details on the architect). It’s an early example of a modern type that has now been copied in many urban areas.

There were several cars parked in front of it which I airbrushed away. Cars do so spoil the aesthetics of the street. They should all be parked out of sight, or better still, banned for towns and cities.

Cervantesgasse

This is a rather zany delight. Just when you thought that the architecture of Red Vienna was an understated gothic modernism, you bump into this; a playful and exuberant call for a return to the baroque.

Built in 1928 to a design by the architect Klemens M Kattner. This is one of three blocks he designed for the council housing programme. His main interest was church architecture. I would never have guessed.

And that’s the end of a short tour of a small part of the public housing programme of Vienna in the 1920s.

Please note; the walk doesn’t go in a straight line, it meanders and goes up one side of some streets, and down the other side. It’s probably easier if you take your own map. Your also bound to discover some new things for yourself.

This is part of a series of seven Red Vienna Radical Walks.

1. Ella Briggs, Karl Marx & Modern Housing

2. The Radical Housing of Meidling, Vienna

3. Favoriten and the end of Vienna

4. A Walk along Wahringer Strasse

6. Rabenhof, Vienna: A Radical Walk

7. Red Vienna: A Radical Walk

And here’s an eclectic Red Vienna reading list

This is a small selection of some of the other estates I visited:

Visits to other Gemeindebau

Otto Prutscher was one of the designers involved. Here’s a walk to discover some of his work

Karl Seitz Hof is one of the large estates…and is well designed and well-planned

A fabulous visit to the Sandleiten Gemeindebau

Sunday afternoon tramping in Vienna and a visit to the Josef Wiedenhofer Hof, and surrounding area

A Saturday visit to the Goethe Hof. This is how good public housing should be.

Red Vienna: A Reading List

Here’s a reading list. I keep adding stuff to it.

Resources

There are several excellent web resources. They are all in German but there are several good translation tools on the web.

Wien Geshichte Wiki

https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Wien_Geschichte_Wiki

Der Wiener Gemeindebau

https://www.wienerwohnen.at/wiener-gemeindebau.html

Das Rote Wien

https://www.dasrotewien.at/

Feel free to contact me, particularly if you can add anything to the brief desciptions above.

danny at beingdigital dot co dot uk

Here’s a presentation I delivered on ‘Housing is more than. houses’. It gives some context and examples of public housing in London, Paris, Brussels, Frankfurt and Vienna

You must be logged in to post a comment.