Empire

Latin: related to imperare, whence imperator, Emperor,

1. Supreme and extensive political domain

2. Absolute sway, supreme control

3. Emperorship – 1606

Corruption

1. The destruction or spoiling of anything, esp. by disintegration or decomposition, putreficatio – 1718

2. Infection, infected condition; also contagion, taint – 1598

3. Decomposition or putrid matter – 1526

4. A making or becoming morally corrupt; the fact or condition of being corrupt; moral deterioration; depravity (Middle English)

5. Evil nature – 1799

6. Perversion of integrity by bribery or favour; the use or existence of corrupt practices (Middle English)

7. The perversion of anything from an original state or purity (Middle English)

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 1933 (revised edition) 1956

At its greatest extent, the British Empire covered nearly 14 million square miles, around 23 percent of the world’s land mass. This included control of nearly a quarter of the world’s population.

In the nineteenth century alone the British Empire was involved in wars in Europe, North America, Myanmar, Afghanistan, the Punjab, Crimea, India, China, South Africa, Egypt and Sudan.

The building of Empire was predicated on the slave trade which began in the 1560s and continued until 1807 when the slave ‘trade’ was abolished. Slavery itself continued until 1833. It is estimated that ships of the British Empire transported over 3 million Africans across the Atlantic, of whom about 10 percent died en route.

In what became known as the triangular trade, cloth, guns and alcohol were transported from Britain, slaves to the Caribbean and the Americas, and sugar, cotton and tobacco to Britain.

Dr. Utsa Patnaik, a Marxist academic, estimated that £9.2 tn was drained from the India economy by the British Empire through trade imbalances, currency exchange distortion (in favour of the British Empire) forced exports, and by using revenues in the country to fund the expenses of Empire.

And what of corruption?

In 2020 the Parliament Intelligence and Security Committee commissioned the ‘Russia Report’. Previous research had suggested that around £20bn had moved through the Russian ‘laundromat’. Another £2.9bn had done similar through the Azerbijaini laundromat.

Weak regulation, shell companies and off-shore banking were all suggested as part of the complicity. London offers lawyers, accountancy firms and financial service companies which will also services for the right price. Some politicians were also no doubt involved.

Corruption isn’t just in money laundering. In 2009 the Office of Fair Trading fined 103 construction companies £129.5 m for bid rigging. This essentially involved companies working together to rig contract price. Over 400 contracts were involved, mainly in the public sector. Some of the hoardings in the city will bear the names of these companies; Kier, Balfour Beatty, Carillion (as was), Laing O’Rourke.

The Libor scandal of 2005 – 2012 involved traders at banks manipulating the LIBOR rate, a global benchmark for interest rates. There were large fines.

In 2012 HSBC was fined $1.9 bn by US authorities for money laundering. This was mainly in the US but there were strong allegations of a London connection.

The National Crime Agency estimates there could be £100bn laundered every year.

Corruption can be defined as corroding, ‘the perversion of integrity by bribery or favour’. It can be applied to tax evasion through the use of shell companies and tax havens and various accountancy tricks.

It can be applied to the corruption of democracy by foreign power lobbying, the use of bot farms and paid-for social media distortions. When I typed in ‘Corruption’ to the search box of the Financial Times the first references were to Trump and Netanyahu.

And the term corruption can be applied to the process of workers selling their labour power; their very essence, in coercive relations of production in order to buy the things they need to stay alive.

It is in this context that the area between the Fenchurch Avenue and the River Thames can be explored. Here can be found a particular geology of history, politics, political economy and culture, woven together by the general threads of the history of London and the world.

It is clear that one is in the City. The identity, the atmosphere, the archeology of the street pattern, the muscular modernity of the office blocks. The types of clothes and fashions, how the people walk in a constrained rush, the snatches of conversation overheard, the way the traffic moves, the brand-image shops, the absence of graffiti, the relative cleanliness, the iconography and symbols of the City of London Corporation.

The architecture of individual buildings and the overall city image create the first impressions. There are stones and shards from ancient epochs, power dynamics from the medieval period, glass, concrete and steel from recent times. Decades of slow change, concentrations of historical events.

Consider the sequence of the English Revolution, Civil War, the Restoration, plague and the Great Fire; all within a time span of less than 25 years. In London the age of Gothic and Absolutist monarchy was over; making way for the curious English Baroque. In Parliament the King was aware of a rival force. In the City the mercantile class emerged in triumph.

And what was the main ambition of this mercantile class? The accumulation of capital. And as Marx states in Capital ‘As capital accumulated, it also became more concentrated’. 1 This can be seen in practice (and theory) all across the square mile.

And through these streets it is possible to determine different ages of capital accumulation. There are buildings from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the period of hand and wood and iron machine manufacturing. Hand made bricks. Groups of artisan builders; the masters of stone and wood and metal working. Human and animal muscle provided the power.

The most modern buildings in this area are being partially manufactured in factories; industrial processes, the application of electrical and computing power. On the construction sites the increasing automation of tools and machines; a worker stands next to a robotic pneumatic drill, controlling it with a hand held device. Add Large Learning Models and then what future for the workers?

Capital expresses itself in the size of the buildings and the power of the City financial institutions. More and more capital pours in. An ever growing expansion of office space. The buildings and their office space are commodities but ones which do not move. They are fixed and cannot be distributed in the way that cars and electronic devices and clothes are. Space becomes a particular commodity form.

Staring point: The Monument

This is an excellent starting point because it is so easy to find.

I arrived early one Saturday morning for a field trip and realised it was just about to open. The London skies were full of raggedy grey clouds, heavy and oppressive, lead lined casks; holding the dead of generations past. The heat of the City is trapped. The world is warming up; wild fires, droughts, crop failures, floods. Switch on the air conditioning, drink the Trump kool-aid, bow to the crazed prophets, worship the anti-science. The world has burned many times before.

There are three people in front of me in the queue. We pay and I wait a few moments for them to get well ahead of me. Then I slowly climb the stairs. I dislike heights and this is an old building. How are the stairs actually held up? This iron railing seems so slight. As I force myself to go higher I become more nervous. Apparently James Boswell experienced the same.

At the top there is a button and notice; ‘in case of emergency please call a member of staff’. But what could they do? How would a heart attack victim be carried down? How to deal with someone frozen with terror by the vertiginous views?

I cling to the railing in front of me while trying to lean backwards against the stone. My hands are shaking so much that I can hardly hold the camera. But I want photographs so force myself forward. It feels as if I will tumble over, into three thousands of history, all experienced in the few seconds of the fall.

The Monument is a memorial to the Fire of London of 1666. The west panel includes Charles II wearing Roman dress. Perhaps the fate of his father encouraged imperial pretensions rather than kingly ones. This is one of the few monarchical symbols in the City; for it is a centre of financial, not regal power. Until 1811 there was an anti-Catholic slogan. A message of paranoid fear.

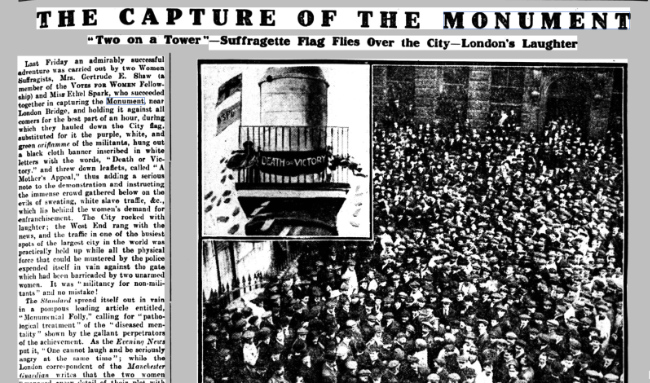

On Friday 18 April 1913, two Suffragettes, Mrs Gertrude Shaw and Miss Ethel Spark, ‘captured’ the viewing platform. They barricade the door at the top of the steps and unfurled a banner, ‘Death or Victory’. From this vantage point they threw leaflets to the increasingly large crowd below. They had carefully rehearsed this action with the use of a model of The Monument itself. 2

The Suffragettes used the publicity to hold a meeting the next day at which over 2,000 people attended. 3

Along Monument Street can be seen Faryners House by Richard Seifert & Partners from 1971. It is now empty and derelict, described as ‘outdated’ and suffering from ‘deteriorating concrete’. Was it deliberate to build with such poor quality?

St Magnus the Martyr

The church is referenced in T.S. Eliot’s work The Wasteland

“the walls of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold”.

Inside the church is a statue of Magnus, an 11th century nobleman of Orkney. He was known for his piety and peacemaking, offering himself as a sacrifice to prevent war. After his execution miracles were reported.

The original church would of course have been Catholic. The rebuilding by Wren after the fire was as a Protestant church, and a particular type of Protestantism at that; Anglican, Church of England rather than fire and thunder Puritan. It is Catholic again and the interior has a rather Catholic air.

The church is currently surrounded by two major refurbishment projects. These are shrouded in sheeting creating an avant garde effect. The whole ensemble is a rather intriguing, albeit unintentional, street art project.

You could just walk along Lower Thames Street in an easterly direction. But it’s more interesting to climb the stairs and use the walkway to Peninsular House. Then follow the walkway, past the tents of homeless people (a counterpoint to the surrounding wealth) and down the stairs at the far end.

Now cross Lower Thames Street again and cut alongside the Custom House for a view of the river.

Lower Thames Street

If you do use the walkway then you will get a better view of the impact of motorism on the urban landscape. This is part of a wider proposal from the 1960s to demolish large chunks of London and build an intensive road network. There is a tension here because the impact of all this traffic retrains the development, and therefore the land values, in the immediate area.

The solution in any fair minded and cooperative world would be to reduce vehicle traffic in London to the minimum. A few yards away is the River Thames which could once again be used to move goods and people in large numbers. The Royals could be used for short sea shipping and warehousing brought back into the city.

If this was pedestrianised then St Magnus, Old Billingsgate and the Custom House could all be bought back to life. Perhaps a giant piece of cloth with a William Morris or Josef Frank design could be draped over the tacky and lurid Northern & Shell building.

The Custom House was designed by D. Laing between 1812 – 1817 with the centre being redesigned by Robert Smirke in 1825. The riverside area is being used as a car park but apparently there are plans to make this a public space.

‘Old’ Billingsgate, by Sir Horace Jones, was opened in 1877. He also designed Tower Bridge, Smithfield Market, Leadenhall Market and the former Guildhall School of Music and Drama in John Carpenter Street.

The building is now used for dinners, receptions, exhibitions and conferences.

The fish market at Billingsgate closed in 1982 and relocated to Poplar. It is possible that this will close in 2028 with no replacement.

Cross back over Lower Thames Street at the traffic lights.

Cross Lane, Harp Lane and Bakers Hall Court

It’s worth going to see this to get a sense of an older City, of manufacturing, warehousing and wharfage. The red brick building appears to be empty and despite hours of research I cannot find anything out about it.

The new red brick building is the Bakers Hall.

What you will find here is an atmosphere from the past. Not a commodity, unless turned into heritage, and therefore worthless to the developers. But of great interest to independent scholars and sidewalk sociologists ever striving to discover the beach beneath the street.

Walk back round to St Dunstan Gardens.

St Dunstan in the East Church Garden

This is a fabulous Gothic ruin and if a modern Dracula arrives in London this will surely be part of their grand tour.

On the night of Saturday 10 May, 1941 a force of 500 Nazi bombers dropped over 700 tonnes of high explosives and 86,000 incendiary bombs. More than 3,500 people were killed or injured.

The main body of the church was destroyed although the tower survived. This was the last day of the Blitz. Five weeks later Hitler ordered the Nazi armies to attack the Soviet Union.

For those in Britain and occupied Europe the end of the war must have seemed like a very long way away.

Walk along St Dunstan’s Lane and turn right into St Mary at Hill.

This only works during the day when the church is open. There is a pointing hand painted on the wall of the church with the instruction ‘ENTRANCE THROUGH IRON GATE’. It’s a good way in.

If the church isn’t open then continue along St Mary Hill to Eastcheap.

St Mary at Hill

The church was rebuilt by Wren after the fire. John Betjeman described it as, ‘the least spoiled and most gorgeous interior in the City, all the more exciting by being hidden away among cobbled alleys, paved passages, brick walls, overhung by plane trees’.

Unfortunately the church experienced a fire in 1988 which left it with no wooden furniture or fittings and scorched edges. Many London buildings were burned down in this decade, often deliberately but this fire is described as ‘accidental’.

However, the rather minimalist interior really does show off the architecture and design.

Walk up towards Eastcheap.

Eastcheap

Eastcheap is decades of differing and sometimes conflicting architectural styles and technical formations of office space. The earlier buildings were built before telephones, networks, computers, databases, spreadsheets and key performance indicators. The modern buildings have fibre optic networks and cloud computing and some of the firms within deal in crypto-currencies.

Note 33 – 35 where the architect Robert Louis (or Lewis) Roumeieu designed a wine and vinegar warehouse for Hill Evans & Co in 1868. It as if one stepped from an opium dream and realised that it was a workday and somehow you had moved from a purple and red room full of gold and rubies and were now in the office; but with no idea of how you got there, or what you were supposed to be doing at work or why. Ever had that feeling?

The building looks as if it is about to be swallowed up. Perhaps it will be.

Throughout 1910 there were adverts in the Suffragette newspaper Votes for Women for the London seller of ‘Suffragette Crackers’ based at 41 Eastcheap. These, the adverts explain, were manufactured by CT Brock & Co under the direction of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

Find Rood Lane and walk north.

Rood Lane – St Margaret Pattens

On the corner of Rood Lane and Eastcheap is the Wren church of St Margaret Pattens, built between 1684 – 7. It experienced little damage during the Second World War other than the windows being blown out.

Being in the curious style of the English Baroque it is simultaneously rich and austere; a dialectical tension that only a powdered Whig could possibly achieve. It has a bold clerestory of round windows and some good woodwork. Note the spiral stair to the organ. New glass was recently added when the church was able to wangle some money out of a new office building that is blocking some of its natural light.

This was all explained to me one morning by one of the church assistants. She was lively and good fun. She told me about a roof problem; something to do with joists and beams. ‘Perhaps it was always like that’, she said, not quite pointing a finger at the original seventeenth century workers. But she was convinced that all the pile driving and the immense weight of more recent buildings weren’t helping. I tended to agree with her.

It is one of the few Wren churches with a spire and once that’s pointed out it’s one of those things that cannot be forgotten. It’s a good carrier of messages and images from an earlier time in terms of style, ideas and commercial practice.

The statues and memorials caught my attention. Something of mercantile London came alive. St Peter Vandeput was a Huguenot from Antwerp. Sir Peter Delme was the son of Huguenot exiles and a powerful merchant involved in the wool trade with Turkey and Portugal. He became a governor of the Bank of England in 1698, four years after it had been founded. I cannot find an accurate history of Susannah Batson who died in 1727. We must assume that she was a person of importance.

There are two canopied pews from 1686 and two sword rests.

Come out of the church and turn right and right again into Rood Lane

Note Plantation Lane, another slavery reference.

Rood Lane – 20 Fenchurch Street

The corner of Rood Lane and Fenchurch Street is a good place to sit down. The official name for the monstrosity is 20 Fenchurch Street but the marketing department will have been in ecstasy when it gained the populist name ‘Walkie Talkie’. I guess we must all have some ambitions.

‘An absolute shocker of a building’ as my companion described it.

‘It looks like design by spreadsheet. The higher the floors, the more revenue. So let’s make the floors bigger towards the top’.

It does raise the question as to whether computing power has ever enhanced architecture, aesthetics and design.

We both agreed that we rather like some of the other work of the architect Rafael Viñoly and are unsure as to what happened to this particular building.

The building was bought in 2017 by the Hong Kong based Lee Kum Kee Company who have been making cooking sauces for the past 150 years. They paid a record £1.28 billion.

While you’re here, have a look around some of the other buildings in Fenchurch Street.

Fenchurch Street – A Small Sample

The ‘market’ relies on perpetual growth of rents and this, along with the pressure of capital to accumulate, is why the City is a never ending construction site. It’s not just the constant knocking down and re-constructing, it’s the endless buying and selling and speculation. Because of these factors no-one involved has any real interest in addressing construction and function obsolescence.

Rather than considering how to build a high tower that might last 300 years, the planning is for a 30 year term followed by a new cycle of demolition-building. This requires a great deal of financing and it seems increasingly the case that large asset managers can default on some loans while still acquiring new loans; and selling at a loss while they continue to expand their property portfolios. This I must research more.

30 Fenchurch Street was built on the site of Plantation House. The name, ‘Plantation House’ was another direct reference to slavery in the development of the City. The name was changed in 2020, partly in response to the Black Lives Matter movement.

The building has over 500,000 sq feet of grade A office space. It was developed by British Land in 2004. It was sold by Safra to Brookfield in 2021 for £635 m. It’s rental value is £79.50 per square foot.

Brookfield is a Canadian asset management company which co-owns Canary Wharf Group with the Qatar Investment Authority.

Safra bank was founded in Aleppo, Syria in the mid nineteenth century. It’s origins were in providing finance for trade caravans across the Ottoman Empire. It is now a private bank with ultra wealthy clients. When Joseph Safra died in 2020 he was considered the world’s wealthiest banker.

The J.Safra Group has assets of over $345 bn and 35,000 employees.

158 – 159 (on the left of the photograph) is in a classical revival style by Leo Sylvester Sullivan, 1911. Telephones were slowly replacing messenger boys as a means of communication.

155 Fenchurch Street (in the centre of the photo) was built in 1984 with subsequent refurbishments. This is the time of the development of the internet. By the latter part of the 1990s, the world wide web, business email and Access databases had appeared.

153 Fenchurch Street (on the right of the photo) dates from 1880 and is by Osborn and Russell. It was built for Samuel Tull & Co, a firm of rope and net manufacturers. Note the cartouche of a rowing boat with ‘Established 1740 – Tull – Fenchurch Street’.

The typewriter had been invented in 1873 and by the 1880s the machines were more reliable and beginning to be widely used in offices. Imagine the day the first typewriter arrived here? Let’s pretend that was the year 1885. If there was someone in the office that day who was 60 years old, they had been born into a world where there were no passenger railways.

Opposite, at no 10 Fenchurch Street, a company existed before the First World War that offered general typing services.

143 – 149 Sackville House was built in 1921, probably as speculative office building. It’s an attractive building with a strong Art Deco form but its history is proving elusive.

Now walk east along Fenchurch Street.

Fenchurch Street – Fountain House

This was the first building in London to use the a tower and podium design. It references Lever House in New York. One can imagine the excitement when it was completed in 1958. The architects were W.H.Rogers and Sir Howard Robertson. It provides a sense of how London might have developed in the 1950s into a New York style city image.

Demolition is scheduled to start in 2026. Apparently tower and podium is now ‘outdated’. The main developer will be CO-RE on behalf of Aviva Investors (the asset owner). Arup will be the main engineers for structures and MEP (mechanical, electrical and plumbing).

The freehold is still held by the Clothworkers Company founded in 1528 by Royal Charter from Henry VIII. This was the year of the divorce crisis when the King sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon.

Landownership remains a contentious part of English history. Reflect here that a great deal of land ownership, including that of the Crown, has its origins in extensive violence. The dissolution of the monasteries and seizure of church lands by Henry VIII transferred a great deal of land and money wealth to the monarchy.

Turn left into Fen Court.

Fen Court

There’s a small garden with some planting, perhaps some tulips if it’s the spring. It’s a good place to have a rest and a snack. Absorb the sculpture.

It’s ‘The Gift of Cain’, by Michael Visocchi with text by Lemn Sissay and commemorates the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. It was unveiled by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 2008.

Fenchurch Avenue

And suddenly the atmosphere has changed. This is shiny, this is new, this is grade A1 office space. No crumbling concrete, tired facades or anything that’s date. This is the future. It too will last about twenty years and then fashion, caprice, speculation, rent increases and the insatiable pressure for capital to expand will make it all redundant. And then the whole cycle of destruction-construction will start again.

It’s worth walking around the buildings; perhaps up to 122 Leadenhall Street, just for a peek. But that area is the subject of a different walk. It’s just the edge you want to see, and save the rest for another day.

Come back to Fenchurch Avenue and walk through Hogarth Court which is the undercroft for One Fen Court, built in 2017. The funding came from General Real Estate, Italy’s largest insurance company.

If it’s open you can visit the sky garden. No need to book and currently it’s free.

Cross Fenchurch Street to get a better view of the building. Taste is complex and I don’t know why but I rather like this.

Now walk a few yards westward along Fenchurch Street and turn left at Mincing Lane.

Mincing Lane, 1 – 2 Minster Court,

Mincing Lane also has an association with the Suffragettes. The ‘Women’s Tea Company’ run by the Gibbons sisters was based at number 9. It offered tea, coffee, cocoa and chocolate, ‘of the very best quality at moderate prices’. And, ‘if orders are of sufficient quantity the goods will be packed in National WSP Union colours’. 4

There were a number of tea shops run by Suffragettes across Britain, and tea drinking became a symbol of protest in its own right.

And today there is yet another huge office building which is about to be demolished. All the buzzword boxes have been ticked; sustainability, public consultation, public realm, wider social benefit.

It might be imagined that it was built so long ago that it bears marks of the last ice age. It was in fact completed between 1991 – 92. However. It is ‘increasingly out of date’ and ‘The office space is inefficient and has poor accessibility. It also has few wellbeing features that office tenants are increasingly demanding in the City’.

The marketeers continue:

“Our vision for 1-2 Minster Court is to create a new City destination, that becomes a City institution. A re-imagined place, that will be a landmark in sustainability, have amenities to attract global talent, with unique public access and a wider social benefit”. 5

How soon before all these marketing departments are run by Large Learning Models? Or perhaps they already are. Who could possibly tell the difference.

And while it’s still standing, it’s possible to go into the building itself. There are a couple of bars and restaurants and a huge pub. One last chance to get the full post-modern, 1980s, Thatcherite yuppy experience. When mobile phones were the size of house bricks and it was still just about possible to get a free dentist on the NHS.

Our age yet lacks a label.

The age of want or that of plenty? The crushing of the soul by capital or the age of liberation?

Are we on the starting line for the future or at the end of time?

Empire of Corruption: A Radical Walk

Thursday 10 July, meet at The Monument, 5.30pm

Book in advance for a tenner, chip into the hat on the day, or if you’re hard up, come for free

- Capital Volume 1 Karl Marx p 594 translated by Paul Reitter, edited by Paul North, Foreword by Wendy Brown ↩︎

- Votes for Women 25 April 1913 ↩︎

- Votes for Women 2 May 1913 ↩︎

- Votes for Women 6 Sept 1912 ↩︎

- https://1-2minstercourt.co.uk/ ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.