This walk illustrates the scale of the house building by the Red Vienna council between 1919 to 1933. Several of the buildings were designed and constructed in the mid 1920s. There is a feeling here of confidence and optimism. Many of the changes which had been implemented by the social democratic council – a progressive tax system, the re-organisation of the city administration, the creation of new supply chains, reforms in welfare and education – were beginning to produce the results they were designed for.

The house building programme of the city, accompanied by welfare reforms and the development of a large, city wide cultural sector, consciously set out to make several changes. To act as a way of building socialism within the city, to act as physical markers of progressive ideas against reaction, to bring into view the most essential class of people in Vienna; the working classes, and to improve the physical and social conditions of that class.

The housing deliberately presented an alternative to the world of poor quality housing, oppressive landlordism, excessive rents and lack of tenants rights. It was good quality build with attention to materials, construction, design, architecture and decoration. Tenants had rights and rents were low.

The housing was managed by the city council which provided democratic accountability through the electoral system and engagement through the trade unions and social democratic party structures. In a system of private landlordism, complaints can simply be met with evictions; in a system of democratic control, complaints must be taken seriously.

The housing was built with tax revenues, including property taxes whereby the rich proportionately paid more. Hugo Brietner, the Director of Finance announced that there would be no debt. Capital costs were written off and rents were to be used for maintenance and repair.

This meant that the housing was, and is, in some ways a non-commodity form. This is a different approach to one in which housing is a commodity, a source of profit, an active accumulation of capital expected to expand capital and accumulate further capital. The purpose of the housing was to provide housing, rather than to act as speculative assets and as instruments to increase land values.

Starting Point

This can be done as a circular walk with the starting and end point being Längenfeldgasse U-Bahn station which serves lines U4 and U6. I would allow 2 -3 hours for the walk itself. It’s long-ish (but less than 10,000 steps) and if this is the only walk you do of the housing of Red Vienna while you’re in the city you will see and learn a great deal.

Coming out of metro stations can be confusing. You need to look for Rechte Wienzeile. With the station entrance behind you there will be a Billa and Apotheke in front of you. Turn left and follow a rather grungy path round to Kobingergasse. Not quite the land of the Habsburgs and a useful reminder that Vienna isn’t a sanitised wedding cake. Follow this round to the right and then cross Schönbrunnerstrasse and continue along Kobingergasse. There’s a police station on the corner to your right. Cross Arndtstrasse and go into Malfattigasse. On your left hand side is Fröhlich-Hof.

Fröhlich-Hof, Malfattigasse 1-5 1928-29 Engelbert Mang

The estate has three sides which means that the courtyard opens out to the street. This creates a great deal of space and both opens out the housing to the world and yet retains a great deal of privacy.

The type of topology, of housing and workshops surrounding a courtyard, had been developed in Vienna from the Beidermeier period onwards and there are still examples of this across the city.

In the courtyard is a sculpture by Stanislaus Plihal of four putti carrying a globe. Look out for the three frogs which act as a water spout.

The housing was named after Katharina Fröhlich (1800–1879), ‘the ‘eternal bride’ of the poet Franz Grillparzer. She created the Grillparzer Prize in 1879 to help impoverished artists and scientists.

If you have the time and inclination, you can walk further along Malfattigasse to Malfattigasse 7 and Malfattigasse 13 (see the next two sections below). If you do this, when you have finished turn around and walk back to Fröhlich-Hof and then turn right into Arndstrasse. On the right hand side is some new housing. You are heading towards Haydn Hof. When you reach Haydn Hof, turn right into the estate.

Malfattigasse 7 1931-32 Stefan Fayans

Within capitalist relations of production, markets are treated as sacrosanct. Allegedly only markets can deliver competition, and only competition can produce innovation and drive down costs and prices.

Markets in fact create huge distortions (just look at the housing ‘market’ in London), waste, inefficiencies, unaccountable bureaucracies, profits for the few, expenses for the many.

Once the theoretical principles of Red Vienna became established, air, light, space, nature, and the financial and administrative structures were created, it became possible to roll out housing on a large scale in an effective way. Everything about the housing programme could be scaled up and adapted, regardless of the type or size of individual plots of land.

Malfattigasse 13 1930 – 31 Johann (Hans) Zamecznik

Here’s another example; a plot of land becomes available, apply the theory and practice within a political and regulatory framework and housing is built that lasts a hundred years.

Every part of the housing, regardless of size or location embodies the same high quality standards. It is a mix of politics, architect and design theory and practical application; all with the ambition to improve housing for the working classes.

Standardisation was applied to doors, door handles, windows, fittings and so on. This helped to keep costs down and, regardless of the architectural form, helped to create a visual identity of the public housing.

I’ll just repeat the directions above. Turn around and walk back down Malfattigasse until you reach Arndtstrasse and turn right. Within a few yards you will see Haydn Hof in front of you. It’s about 300 metres.

Haydn Hof, Arndtstrasse 1927 – 1928 August Hauser

Named after the Austrian composer Josef Haydn, the estate was built between 1927 – 28. There are three monumental entrances to the estate; on Arndtstraße, at the Gaudenzdorfer Gürtel and on Steinbauergasse. If you walk through the courtyard of the estate (which I would recommend) aim to come out of the one on Steinbauergasse.

There are interesting demarcations between public, communal and private space around and through the estate; but they never feel policed in the way pseudo-public spaces are.

On one of my visits to the estate it was being cleaned by workers from Wiener Wohnen which is a department of the Vienna City Council. One department to do the cleaning across the whole city and a line of accountability through local elections.

It would be interesting to know how the overall costs compare with local authorities in Britain which have now outsourced so many services; and what trade unions density is like, rates of pay and so on.

The estate has a pleasant internal courtyard within which there is a separate kindergarten and waschsalon (communal laundry). The waschsalon was a common feature of the larger estates. Centralised communal launderies could provide a range of equipment which would be outside the budget of working class families at the time. And by centralising laundry machinery it meant it wasn’t in the kitchen taking up space.

Previously working class women (as it was almost certainly was women who did the laundry) would have to boil clothes using water heated over coals or wood. This was arduous and time consuming.

At one point it was suggested that laundry would become a professional occupation; people could drop off their clothes, bed sheets and so on in the laundry and collect it when it was done. The laundry workers would be paid professionals. This never happened.

But the laundries did become women only spaces and one wonders what the implications of this was. In some ways it reinforced stereotypes, but it also bought this type of domestic work out into the open. Everyone would see women carrying the washing to the laundry and knew that the women were doing this work.

All the supervisors were male; one of those weird things that just don’t make sense. At this time most working class people did not have a large wardrobe of clothes and women would strip down to petticoats and underwear to do their washing.

The courtyard was the scene of fighting during the civil war in February 1934.

As you come out of the other side of Haydn Hof you will be at Steinbauergasse. On the other side of the road you will see Leopoldine Glöckel Hof

Leopoldine Glöckel Hof, Steinbauergasse 1931 – 32 Josef Frank

You could either walk around the courtyard or head for the opposite corner on the right hand side. I always walk around the courtyard; you get a better sense of the estate.

This is a closed perimeter building with an attractive inner courtyard. The mass of the building is broken up by the use of soft pastel tones. It gives the impression of a series of tall houses rather than a horizontal facade of apartments. The balconies add a symmetrical rhythm. You will see them when you come out the other side.

The optimistic energy was draining away from Red Vienna at this time and yet Josef Frank created something solid, permanent and impressive here.

It can be read as a subtle statement; fascism and the right simply destroy all that is good and enrich themselves through venality and corruption.

The opposition to this is something socialistic, collective, based on unity and solidarity. There is a gentle atmosphere about the courtyard and the estate that I like a great deal.

When you arrive at the right hand corner there is a passageway out of the estate to Hethergasse. Turn right and then left into Siebertgasse. As you walk along, look to your left and you will see Reumanhof. I would suggest you leave that for another day.When I am next in Vienna I am going to create a separate walk for that area. There appear to be organised walking tours around that area you might be able to find.

Turn right into Koflergasse and then left into Schallergasse and then right into Flurschüutzstrasse and then left into Wolfgangasse. It sounds much more complicated than it actually is. It’s just to create a bit of variety and to show some other streets. On your right hand side as you walk along Wolfgangasse is number 54.

Wolfgangasse 54 1930 – 31 Rudolf Karl Peschel

There is one central entrance which leads into a communal courtyard. Here, and in other Gemeindebau the courtyard was a benefit to all the housing and to all the tenants in the housing; be they private tenants or those who were tenants of the city council.

This was conscious and deliberate; to open the space up to everyone. Before Red Vienna housing also had courtyards; but it was generally reserved for the landlords and property owners.

The courtyard creates a central space of air, light, space and green for everyone. It is a democracy of spatial organisation based on socialistic ideas. This approach benefits everyone equally, rather than a few.

This type of spatial and topographical organisation highlighted the differences between the progressive, good quality, low rent housing of the socialist council and the reactionary and oppressive poor quality and high rent housing of the private landlord sector.

This sort of political intervention in the urban space of a city is unheard of in Britain today.

You could continue a few metres along Wolfgangasse and go and see Elisabeth Schindler Hof which is new.

Elisabeth Schindler Hof Wolfgangasse 2022

This was opened in 2022 and contains a mix of apartments to accommodate a range of family types including large families and single-parent households.

The block has a community garden on the roof and a kindergarten. It’s also an attractive design and hopefully it’s well built. To me it is like a key to open the next stage of my research: housing in Vienna from 1945 onwards.

If you did go and see this, now turn back on yourself. You need to turn into Karl Löwe Gasse. Look out for no. 4 on your right hand side

Karl Löwe Gasse 4 1929 – 1930 Anton Potyka

One of the characteristics of this walk that I like – and I hope you like it too – is the mix of housing types. There are large estates and there are small blocks like this.

And what is illustrated in the built environment is a democratic commitment to all of the housing provision, not just the housing that is big ticket. It would have been easy to have created a bland facade here. It’s less than 20 apartments.

Instead there is as much attention to detail as in the large blocks and statement buildings.

The balconies create open, outside living space; to sit and drink coffee in the morning and the afternoon, and beer and schnapps in the evening.

Here the world can be discussed. I would bet that the world was put to rights many times over on these balconies, and I would suggest that the solutions offered up by the tenants were often better than those offered up by the majority of European politicians.

Continue along Karl Löwe Gasse and then turn into Fockygasse. Number 53 is on the right hand side. On the other side of this is Fockygasse 44

Fockygasse 53 1930 – 32 Bernard Pilcher

The building has a recessed front courtyard. It is shallow in depth and yet provides an effective spatial barrier between the street and the building. An element of privacy is introduced and yet the space is also part of the street, and of the city itself.

Creating space in this way is a clever application of design skill.

The statues are in natural stone by the sculptor Rudolf Schmidt. I like the sense of identy that these sculptures provide. I imagine how children would identify with them, think about their curious shapes and complex messages; how the sculptures would enter the imaginations of children, provide a sense of place; ‘this is where I live, it’s my home’.

Fockygasse 44 1933 – 35 Franz Wiesmann

The building was constructed between 1933 – 1935 and was privately financed.

At the moment my research is from 1919 to 1934. This housing represents an end point to that period. It is also a starting point, a question as to what happened during the period of Austro-Fascism, Nazism and post-war reconstruction? The building raises many different questions.

Federal support for the housing of Red Vienna was withdrawn in 1929, the same year as the Wall Street Crash; although the city council continued to build.

The architect was Franz Weisman. The plainness of the building, the lack of decoration and statues, the lack even of a name and inscription, raises the question as to how much financial considerations were becoming more dominant.

In the world of profit-centred commercial housing everything has to be paid for, everything is determined by costs; the quality of the materials, the craft skill of the labour, the aesthetic of the design. The principle of ‘home’ is sacrificed to the spreadsheet, financial projections and profitability of ‘housing units’.

Go back up to Karl Löwe Gasse and turn right. Walk a few metres and then on the right hand side is Karl Löwe Gasse 12

Karl Löwe Gasse 12 1929 – 1930 Jacques Schwefel

The appreciation of architecture is like the appreciation of any form of culture; it’s subjective. And even in our own inner life we may struggle to explain why we like particular things. Personally, I think this is great.

This is an infill building, Lückenverbauung, which is far harder to achieve well than it might appear.

The architect is restrained by lack of space and there are a lot of pressures from existing buildings. Of course all that could be ignored. A giant glass box with an eccentric shape could be imposed.

This happens all over London. It is driven by commercial interests and therefore a huge marketing and PR industry must work hard to tell everyone how marvellous it is. The reality of profit and greed must be disguised with the mantra of ‘opportunity, community and sustainability’.

A building like this doesn’t need a mantra. It just valorises through time, always enjoyable, like a Miles Davies trumpet solo.

Little is known about the architect Jacques Schwefel. He was Jewish and came from a humble background. This is the only building known to have been designed by him as part of Red Vienna. He and his wife managed to migrate to the USA to escape the Nazis but then his biography is lost to view.

Continue along Karl Löwe Gasse and then turn right into Malfattigasse.

Malfattigasse 39 1929 – 1930 Klemens M. Kattner

This represents a more simplified form of architecture which starts around 1930 but it still embodies the generalised elan and spirit of the time of Red Vienna.

Everything has a quiet dignity; everything is done well. There was something about this building I liked a great deal. The courtyard had a particular tranquility. Perhaps it was the time of day, perhaps it was because I’d already done this walk two or three times and no matter how often, I always enjoyed it, it was becoming familiar and I noticed different things on each occasion.

Continue along Malfattigasse and then turn sharply to the left into Rizygasse. You will Reismann Hof in front of you.

Reismann Hof, Rizygasse 1924 – 25 Heinrich Schmid and Hermann Aichinger

This is one of the first of the large Gemeindebau of Red Vienna. There are a number of separate buildings which are linked together with open space, arches, paths and the roads that run through the estate. It was planned to be integral with Fuchsenfeld on the other side of Längenfeldgasse.

Reismann Hof was named after Edmund Reismann, a Social Democratic who served as a city councillor and member of the state parliament. He died in Auschwitz in 1942.

It is probably best to explore this for yourself as I think it would be too complicated to try and describe a route through and around the estate. And these notes are intended as pointers not as dogmas. There is always something pleasurable about finding things, rather than being told about them.

I would suggest however that once you have gone through the main arch (which says ‘Reismann Hof’ above it) turn left towards the kindergarten and explore that part first. You will find statues of children playing instruments and much else.

The kindergarten is still in use. These are impressive buildings in their own right and are part of the physical built commitment to improving the living conditions of working class people. Infant care, child development and support for teenagers were all taken seriously within the Red Vienna programme.

You could come out of Reismann at several different points. When you’ve finished you need to find Längenfeldgasse. On the other side is Fuchsenfeld Hof. Go through the large archway and then head towards the corner on the right hand side. There’s a way through and you can explore the courtyards of the estate.

Fuchsenfeld Hof 1922 – 25 Heinrich Schmidt and Hermann Aichinger

Schmidt and Aichinger were both pupils of Otto Wagner in the 1900s. There were many more applicants to Wagner’s courses than places. He taught in a rigorous, technical and imaginative way. In their first year all pupils had to complete an assignment on housing.

Carl König also taught at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). He concentrated on technical ability and a close study of classicism, insisting that only through such an approach could new styles emerge.

I would draw an analogy with the German group Can; classically trained musicians who were able to create unique avant garde music.

Could you listen to Can, Captain Beefheart, Louis Armstrong, David Bowie, Mozart and Richard Wagner in such housing? I certainly could.

The purpose of this housing was to be the basis of a home. A good home will help a person develop, enjoy and discover. All sorts of things; music, films, art, self, each other.

The construction of the large-scale Gemeindebau was consciously organised to use large numbers of workers with different skills and that’s well illustrated here.

Steel frames to employ metal workers and scaffolders, brick work to employ brick layers, stucco to employ plasters. Wrought iron work, lanterns and lamposts, stone work and sculpture. The art isn’t tacked on at the end, it’s integral to the totality of the building itself.

We generally experience architecture from street level or within the building itself. There is a good range of perspectives across the estate.

Fuchsenfeld was also a scene of fighting during the civil war in February 1934.

I would suggest to just drift through Fuchsenfeld. It’s one of the first large scale Gemeindebau that I ever really walked through and it had a big influence on my thinking about housing in general and Red Vienna in particular.

When you want to move on, come out of the estate at Karl Löwe Gasse. In front of you will see Wilhelmsdorfer Park. Walk across the park towards the corner on the right hand side. You will come to Deckergasse and Deckergasse school. Turn left into Längenfeldgasse. On the right hand side is Böckhgasse and Liebknecht Hof

Liebknecht Hof, Böckhgasse 2-4 1926 – 27 Karl Alois Krist

This is another one of those estates which are best explored through a rambling interaction. The built mass has a great deal of personality; and yet the individual character of its components is all predicated on the social, collective use.

The original wrought iron gates are by Karl Krist.

The laundry is still in use. One afternoon I sat nearby for a couple of hours, sketching and watching the world go by. With a half closed eye I observed the people going in and out of the laundry.

Elderly working class women with shopping trolleys full of cloths. Middle-aged blokey-men, the sort who drink and smoke too much and never get asked to dinner parties. You used to meet such types in local pubs. They could be good company. Bright working class radicals with broad minds and socialistic and progressive views about the world.

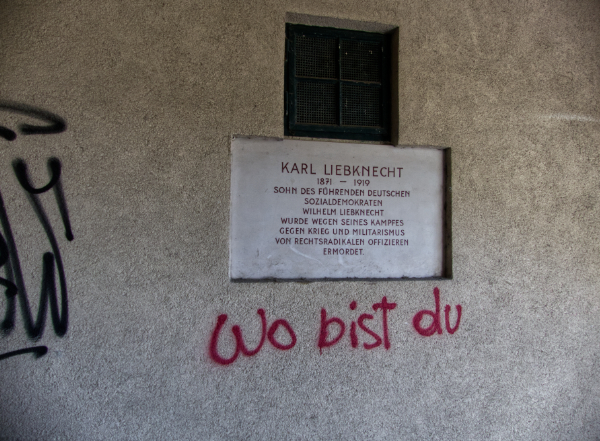

The estate is named after the German revolutionaries Wilhelm and Karl Liebknecht. Wilhelm was a close personal friend of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He lived in Soho near the Marx family in the 1850s. The Marx children Jenny, Laura and Eleanor gave him the nick name ‘Library’.

His son Karl was murdered by proto-fascists in 1919. Fascism grew – aided and abetted by right-wing newspapers, cultural wars and opaque funding from rich and powerful elements within the capitalist class. There were fierce clashes here between the Schutzbund and fascists during the Austrian Civil War.

When you’re ready to move on, find Steinburger Park. You should be heading for the far left corner. This will take you back to Längenfeldgasse. Turn left into Steinbauergasse and there’s Bebel Hof. There isn’t a way through the estate. You have to go in and come out the same way.

Bebel Hof, Steinbauergasse 36 1925 – 26 Karl Ehn

I wondered how many kids cracked their heads and broke bones on this concrete slide? It is now surrounded by a wooden fence and is no longer in use. As a slide it’s a disaster; as a sculpture of a slide it’s a great success. But these are different things.

One afternoon I was in the estate and talked to a local social democratic politician.

“What are the problems?” I asked.

“People moan about everything all the time’, she replied.

Of course they do.

“But’, she added, ‘if anyone tried to take it away from them they would fight’.

I hope they do. For whatever problems there might be they would be much worse if the property-speculator-land-development-profit-making-capital-accumulators took over.

There were originally 301 apartments, eighteen shops and commercial units, five studios and workshops, a large meeting hall, tuberculosis clinic, playground and a paddling pool.

The architect was Karl Ehn who was also a pupil of Otto Wagner. Little known about his personal life. He never married and lived alone.

He is now best known as the architect of Karl Marx Hof which might suggest he was a communist. But no. He was briefly a member of the Social Democratic Party from 1925 – 27 and he worked for the socialists of Red Vienna. He also worked for the Austro-Fascists, the Nazis and the governments of the post-war occupation.

When you come out turn left, and left again into Längenfeldgasse. A few more metres and on the left hand side is Lorens Hof.

Lorens Hof, Längenfeldgasse 14-18 1927 – 28 Otto Prutscher

Otto Prutscher was a student of Josef Hoffman. He also designed glass ware, furniture and much more. There are examples of his work in MAK (Museum für angewandte Kunst – Museum for Applied Arts) in Vienna.

The estate is named after Carl Lorens who was born in Vienna on 7 July 1851. Lorens was a folk singer, composer and poet and considered ‘one of the most important representatives of the Viennese song tradition. He is buried in Meidling Cemetery.

There is a sculpture in the courtyard of a seated woman with a child by Rudolf Schmidt. On a previous visit to the estate, perhaps a year or two ago, the sculpture was surrounded by bushes and shrubs, and if I remember correctly, flowers. Those have all gone, although there does now seem to be a larger play area. What the history of all that’s about would require some local knowledge.

It’s worth going to see the day centre and the waschsalon which are also in the courtyard.

I walked this route several times to try and join it all up. For some reason Lorens Hof always seemed to be the best end point.

As you come out of the estate turn left into Längenfeldgasse and the Längenfeldgasse U-Bahn station is about 300 – 400 metres away. You should be able to see it.

And that’s it. Another Red Vienna Radical Walk.

This is part of a series of seven Red Vienna Radical Walks.

1. Ella Briggs, Karl Marx & Modern Housing

2. The Radical Housing of Meidling, Vienna

3. Favoriten and the end of Vienna

4. A Walk along Wahringer Strasse

6. Rabenhof, Vienna: A Radical Walk

7. Red Vienna: A Radical Walk

And here’s an eclectic Red Vienna reading list

You must be logged in to post a comment.