The bus pulls into Princess Street. I consider how it is that the blue of the sky that I noticed the day before had made its presence felt in my dreams. A blue silk and movement and something so close and yet; a phantom, not real, to try and touch, an impossibility.

In the street. The amplification of pose.

Into the Scottish National Gallery. The first painting is magnetic. Grifo de Tancredi, The Death of Ephraim and Scenes from the Life of the Hermits. And in the wings of the triptych, Scenes from the Passion of Christ. Painted around 1280 it is an object that is over 700 years old; created as a non-commodity. Or was it? When exactly does capitalism commence? Has the formation of capital begun?

It is like watching a frozen film. All the scenes are here, laid out in static panels. And yet it moves. It pulls me into dimensions beyond time and space.

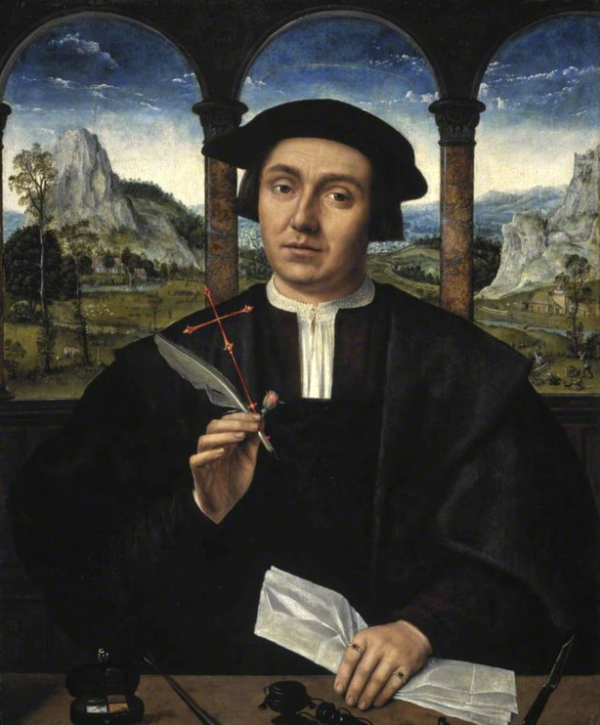

Nearby is The Portrait of an Unknown Man by Quentin Massys. His father was a black smith, his son Jan the painter of the enigmatic Flora and allegedly a member of the Family of Love in Antwerp in the 1550s.

The man is surely a merchant, or administrator, or lawyer or member of a profession. He is bourgeois. He holds a cross and has a halo; but x-rays reveals these are later additions by an unknown hand.

Originally he held a carnation. There was no halo. He was secular when first painted around 1510 but some time after this religious iconography was added. Was this during the time of the Reformation, iconoclasm or Counter Reformation?

It is easy to assume that all paintings embody politics; much harder to assess what these politics mean and how they are expressed. As far as I am aware Massys didn’t write a screed about what he meant with the painting (is this just a modern phenomena?). The painting stands alone, free from much in the way of adherent signals other than some basic metadata (see Kubler The Shape of Time).

The man is in the foreground, and in the background, both connected and disconnected, is a large city. It appears to be gothic and medieval. And yet the man is framed by classical architecture.

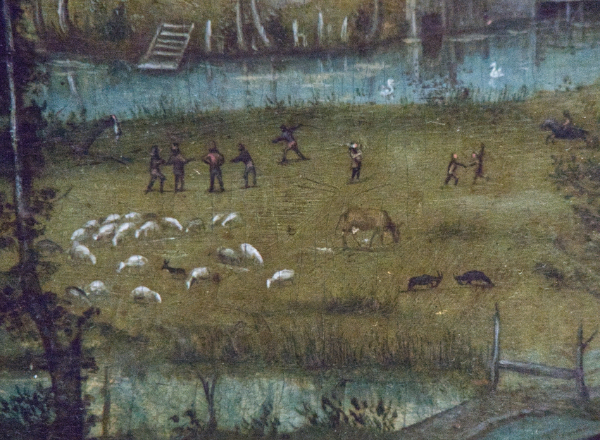

In the background a whole world of life and production. A woman milking a cow, someone pushing a wheelbarrow. A flock of sheep. People shaping stone (or wood?).

Clothe has been laid out on the grass, perhaps in the process of being bleached or dried. A wagon is being pulled by horses towards the city, someone is leading a laden donkey along the track. A group of peasants, they appear to be dancing. Perhaps dancing was part of production. Now dancing and production are very separate things.

It’s the year 1510; it could be concluded that these are features of the rise of capital. They are also features of feudalism. They are also features of production in antiquity.

But why have features of production appeared in this painting of the early 16th century in this way? Why was it that the original painting had no religious display, and why was such display painted later?

The break however is much earlier. There are secular images that date back a hundred years before this. Jan Van Eyck and The Arnolfini Portrait and his Portrait of a Man from 1433 and 1434.

The latter is most worldly and lacks any sense of mystification. Religious painting (certainly in the North Renaissance) continues. New types appear however; figures with title deeds and contracts in their hands and money-coin upon their tables.

This man holds a sheaf of paper. What does it represent? A bill of trade? An inventory of a the contents of a warehouse or goods to be transported by sea or canal?

The formal landscape is fictional, perhaps the Ardennes, perhaps the Alps; perhaps a reference to the flow of trade between Antwerp and Augsburg, and then to Venice and the north Italian city states.

Inside the Massys workshop. The apprentices are mixing colours, making preparations, being taught to draw and paint. The guild masters discuss form, shape, colours, proportions, foreground, background; the gossip of the town, theoretical and philosophical ideas.

Ideas dissolve, dissipate, reconstitute into something else. We are all in this process all the time, throughout time.

In 1510 the gothic is being replaced by the classical in fashion, style, ideas.

Something that will become known as ‘capitalism’ is making changes in the organisation of labour, the work processes, labour processes, the governance of trade and manufacturing.

Near to Massys’ painting is another Portrait of a Man. It is from the Netherlandisch School but not directly attribute to any particular artist. Perhaps it is Jan Gossaert. The painting is dated from around 1525, only 15 years later than the Massys portrait.

The man is the foreground. There is no background at all. There is blue sky where God, Christ, the angels and saints once appeared.

Today, the early days of 2026, one phase of capital is being replaced by another phase of capital. These transitions always led to eschatologies; a rush by the leadership types to herald the age of catastrophe, to express their leadership qualities by their ability to predict the end of time.

Someone must remember to paint pictures of Lenin on the lapels of their jackets. And to only photograph them when they hold cold statues of Marx and Engels in their hands.

Their hearts are made from wooden blocks with holes where the worms of time have hollowed through.

I discover The Virgin and Christ Child and long to visit Ferrara. Soon would be good, but five hundred years or more ago even better.

But would I simply see it all through the blurred lenses of current prejudices? Could the enigmatic mystery be appreciated, even if it would be impossible to comprehend? How would we stand if transported to those medieval streets? How would we experience the sensations of that time?

The surfaces that we live in, fashions, vogue, misrepresentations, ideologies; pose would little prepare us for what we might find.

In Princess Street again, in a shoe shop. The shoes are made of nylon and plastic. I find them ugly, ungainly, I doubt their comfort, weather proofing and durability. We are all consumers, consuming and consumed.

I cannot write that Edinburgh may be this or that. But it is dominated by money, as all cities are. And the scramble for money, and the lack of money, and the greed of money. Few if any guide books begin an introduction to a city with money; but when you think about it, what better place to start? Money shapes the world.

A girl walks past with her hands deep inside the pockets of the long grey coat she wears. A girl walks past all in black; she has black hair and black eyes and big boots, the only colour, a hint of darkest cherry red; she has the shy confidence of an emerging rebel.

We spend one afternoon exploring public housing. Good quality, well built council estates; now much privatised. The urban plan is good, they have substantial gardens, space, light, air.

We consider; that not so long ago as old year’s night disappears the estates would have been full of people first-footing and friendly revelry. But now they are silent.

It’s not immigration that brings such change it’s the changing needs of capital. Multiple-shifts, work exhaustion, atomisation, privatisation, alienation, domination of digital media, the spread of fear by the right wing press. It’s as if a mass of people want to come to life again but don’t know how.

I take several walks through and around the New Town with the crescents, places, squares, gardens. These perambulations shift and expand my thinking on urban planning and design.

I have found a great deal that is of value and yet cannot make out its worth. It is like finding one of the lost books in a forgotten bookshop. One takes it to the counter with hesitation, almost floating, a heightened sense of reality but a lesser sense of realism, dreamlike, the swirl of subterranean ideas, a dimension yet to yield to the boundaries of physics.

The book has to be opened slowly, read one word at a time, beyond translation and yet so clear, lucid and immediate.

I walk to Leith and shapes change inside my mental templates.

I was born in Leith and lived there as a baby and small child. Every time I visit I have a profound sense of something that I cannot explain. It is not sentimentality or nostalgia; it is a sensation that I have never experienced anywhere else. The only way I can attempt to describe it is like this. Imagine you have a shape in your mind, let’s say a building.

Let’s be more specific and imagine a building like a nineteenth century stone warehouse (see the photograph, the building on the left). Square with a sloping roof. Large rectangular windows. You are not aware of this building shape in your mind.

And you walk along a street and then you are aware of it in a detailed way and you see a building in front of you, in reality, a real building, exactly like that and this shape you didn’t realise you had in your mind is revealed on the dockside. It’s not simultaneous; there is a split second delay and you are aware of that too.

This always occurs on trips to Leith. In different places, at different times. I cannot will the sensation. When it comes however it is profound. There is a vague memory of a tenement type of flat with stairs and shops at ground level. In the corner a television with black and white moving images, static and interference. People moving as if in a dream, my parents. The early 1960s.

The war is less than 20 years in their recent past. The sound of artillery in the distance, getting closer, the Russians are coming. My mother slept in a coffin at night inside a factory in Silesia where she’s from. Then the Russians came.

“The first ones were alright”, she says. But the expression in her face is a book yet to be written.

“They just went through the village. Some threw apples and chocolate. But the next ones…” Then the stories become darker and darker.

She was born in the Weimar Republic and by the time she was twenty had lived through the Nazi period, the Second World War, the Russian invasion and occupation. She had been a farm labourer, Trümmerfrau and refugee.

She once told me a story of how she and some friends had gone out one night – “we had to be very careful there were Russian soldiers everywhere”. She described how they saw their camp and sneaked past them through the woods.

“We wanted to meet boys,” she said, ‘we were young girls”

On one occasion they found a milk churn full of treacle.

“All we had to eat was potatoes”, she said, “but now we had treacle with our potatoes”

Yes, that was my mum in Leith in the 1950s and early 1960s. She liked the people in Leith a great deal. I have a feeling that they liked her too. For she has always been one of the people.

I have a memory of playing skittles on the landing of the stairs.

I think it was Christmas time.

Are these memories reliable? I don’t know but I don’t have others. I have worked to retain them, every so often revisiting them and cataloguing them in certain ways. Has each new iteration of myself changed them?

Now Leith is being ‘redeveloped’ and bland flat pack flats are hastily being built. It is all speculative; based on the needs of real estate capital.

There’s still the echo of an older place, but the voices from further off in time as weakening, their sound is muted, shrill voices over power them.

There is a scattering of ships in Leith docks. Rivits in the metal plates, rust runs down the painted sides; this was once a world of dockers, riviters, seafarers, warehouse workers.

I go into Sainsbury’s local in what was once the dock area. An elderly Scottish woman is buying some groceries and a couple of different lottery tickets. She is being served by a young Asian woman with long black hair.

“Thank you dear”, she says as she carefully puts her lottery ticket in her purse, “Thank you”, she says again.

The basic working class solidarity and camaraderie continues.

On New Year’s Day we walked the streets which were being cleared of the debris from the celebrations of the night before. There were still many tourists around. There was a relaxed sociable atmosphere.

We went into a couple of pubs on the Royal Mile but they failed to attract us and we walked out again. Into The Waverley. The barman was friendly. It’s more of a local pub. Here we find another aspect of Edinburgh, as if there’s been a slip in the space-time continuum and it’s a different year, another time but the same place.

Does a city have a single spirit? Or is it full of spirits, in tension, conflict, opposition, fighting for position; a titanic struggle all around of us of life and death, love and hate, right and wrong, cooperation or atomisation, harmony or discord?

We found a different spirit here; one that wasn’t so easy to hang a label on or put into an easily defined category box. For a timeless moment we were transported; we knew that but were unsure where we had been taken.

We liked the process and the destination. In this new place, which somehow was in the existing place but separate from it, we drank hauf and hauf and found dialectical energy in our conversation which danced lightly and eloquently, as if made of star dust. The words sparkled like diamonds and tumbled elegantly all around us.

It reminded me of a day in Frankfurt, with this same companion.

We had walked through the city as I wanted to see the Altersheim, designed by Mart Stam in the late 1920s. My companion was good natured and accommodating. We then walked back into the city. We ate and then walked further.

We hesitated outside a pub and the mysterious Hans Schnapps and his companions arrived, more or less at the same time. Hans Schnapps introduced himself with a critique of Feuerbach.

I responded with a smattering of Hegel and a deeper undertone of Marx. He introduced Max Stirner.

It was as if we had last been in conversation on the barricades of 1848 and had somehow been separated in the street fighting. Now we had found each other; after such a time.

And all the while the world had developed; revolutions in the means of production, means of communication, vast industries conjured up from the ground, the ongoing class conflict of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. I rather felt that Marx had won the argument in both theory and practice but Hans Schnapps defence of Feuerbach was passionate and convincing.

Our companions took one corner of the bar, and we the other. They debated finance capital, more hard boiled than Schnapps and I.

It was a real shame that Engels wasn’t in town that night. He would have been up for the argument. Marx would have disdained our foolishness and sat in the corner smoking cheap cigars and reading Balzac, occasionally waving his hand to indicate that we should stop.

The pub itself wasn’t of the Heimat-ish and volk-ish genre. It was more Biedermeier. There was something about the gentle symmetry, the stylish simplicity with a dash of ornamentation, the brief appearance of stained glass that acted to separate the benches.

It was a much earlier modernism that both pre-dated and informed the trajectory of Neues Frankfurt. As if there was an counterpoint of modern design that is still unknown.

The Waverley did this for Edinburgh. Here was everything unrecorded, with people of rich auto-biographies never written, a class of people who are written about, who are written for, who are conducted, as an orchestra, to act as a mass for pre-determined political positions, who must all wear certain, acceptable, labels pinned upon their mass produced clothing. To only be seen in the broadest categories of class, denied the thought-trips of self-created internal experimentation.

I sat in a pub in Rose Street reading John Buchan’s book Edinburgh: The Capital of the Mind. Buchan had been my companion for several days and I was enjoying his writing style and getting a great deal from his book. He opened the city up to me in unexpected ways; in thoughtful, intellectual, thinking ways.

We eat in the Mosque Kitchen. A delicious lamb curry and pilau rice. Through an open door, we have stepped into a stream of the world that flows through so many cities. Here is the secret integration of the global proletariat. Where exactly is its voice?

We walked the streets, rode the city buses. In the shopping centre just before closing time with the poor people and the shift workers. Earlier an elderly woman, bent over a stroller, ”Sorry”, she said as she walked in front of us.

“No don’t be sorry”, we said, slowly down. “Take your time”.

She carefully sat down on a bench outside the supermarket

“I need a wee rest”, she said

“Well it’s nice and sunny for you” we replied, and added, “Happy New Year!”

“And a happy new year to you!” she said, and with fight and spirt and some sort of growling defiance which if it could be bottled and distributed would we just the potion to start a revolution.

I can’t sum up Edinburgh; who could?

But reading Buchan and coming out of the pub into the cold and night of Rose Street I would suggest this.

Edinburgh, as all cities is predicated on exploitative relations of production, on the coercion of human labour. That there are many different rates of exploitation at work. That accumulated capital is used to sweat people; that sweating people produce more capital. That capital expands and the process intensifies. And the process produces alienation and atomisation and within this people strive for the antithesis of solidarity and conviviality.

The streets thinned out of people and ahead of me on the narrow pavement a woman with a rucksack and large overflowing carrier bags in either hand.

She is encouraging a small child to continue the walk that never ends. They started from Lviv some months ago. Crossing borders in the night, out of the sight of the searchlights and the border guards. Pressing warm flesh to cold pine needle carpets on the forest floors when the machine guns shoot into the shadows. Hiding in straw and clinging to the chassis of lorries on the autobahns.

I pass them and she turns and stops. I catch her eyes. She is one of the people. The history of the 21st century is already etched there. The memories of the 20th century still unresolved.

Something human momentarily sparks between us. These sparks must become bigger. They must fall on the combustible material. The combustible material of the shared interests of the workers and of solidarity must ignite.

We have the fire and power within us. It is an immense force. We must spark it into life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.